How Memory Prioritization Shapes Our Actions

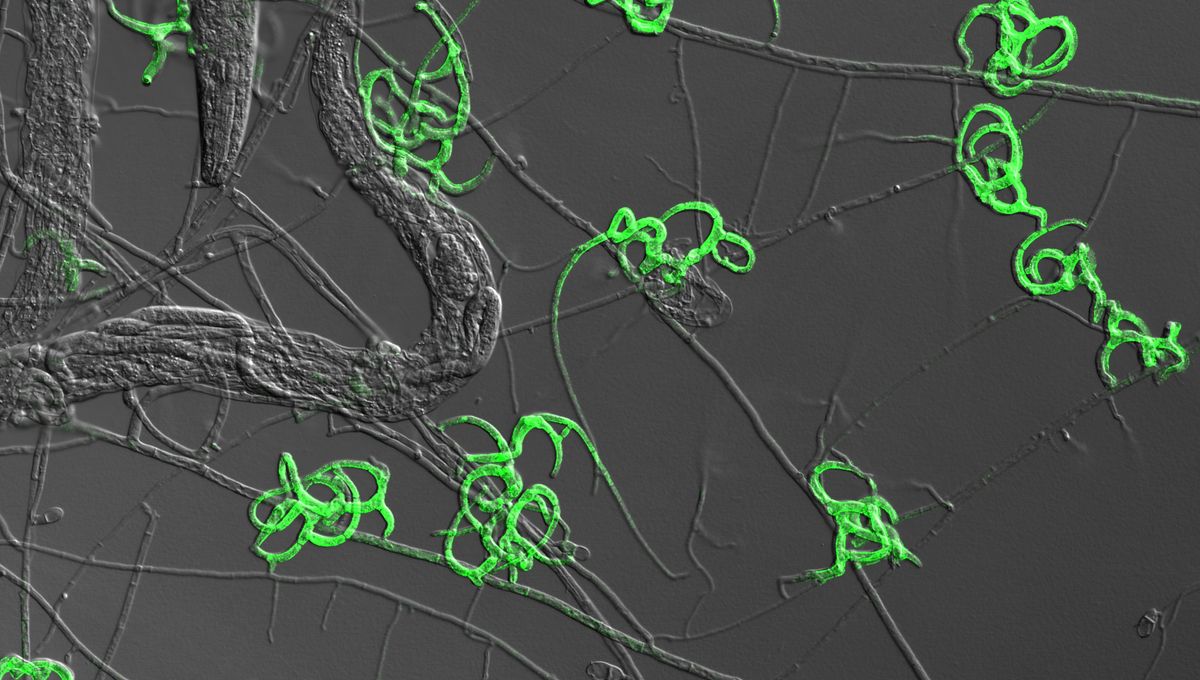

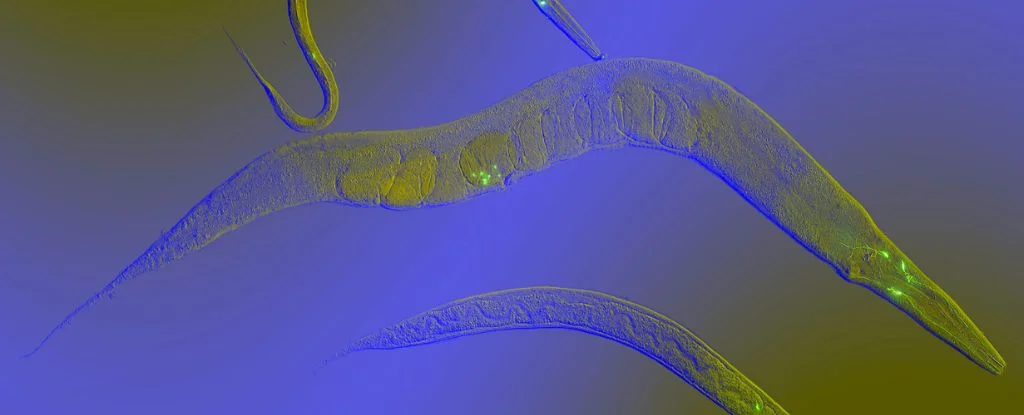

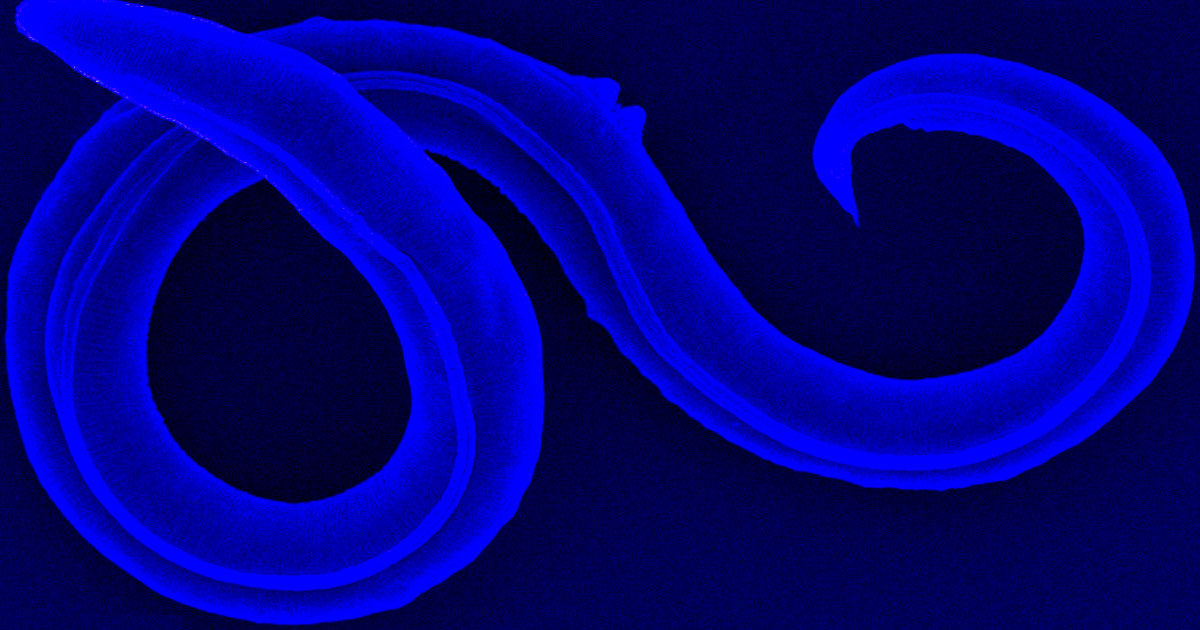

A study by UCL researchers found that male worms can activate conflicting memories of mating and starvation when exposed to the same odor, but only the mating memory influences behavior. This demonstrates how the brain prioritizes rewards over punishments, offering insights into memory-driven behavior and potential applications for understanding disorders like PTSD. The research highlights the brain's ability to adapt and override previous associations, even in simple organisms like worms.