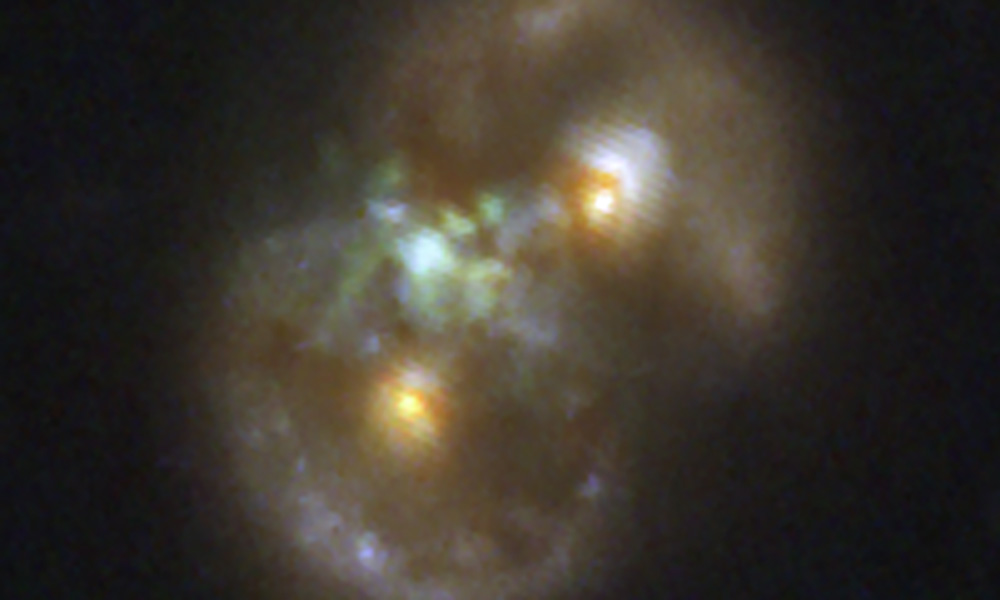

Unprecedented Low-Frequency Radio Sky Map Reveals 13.7 Million Cosmic Sources

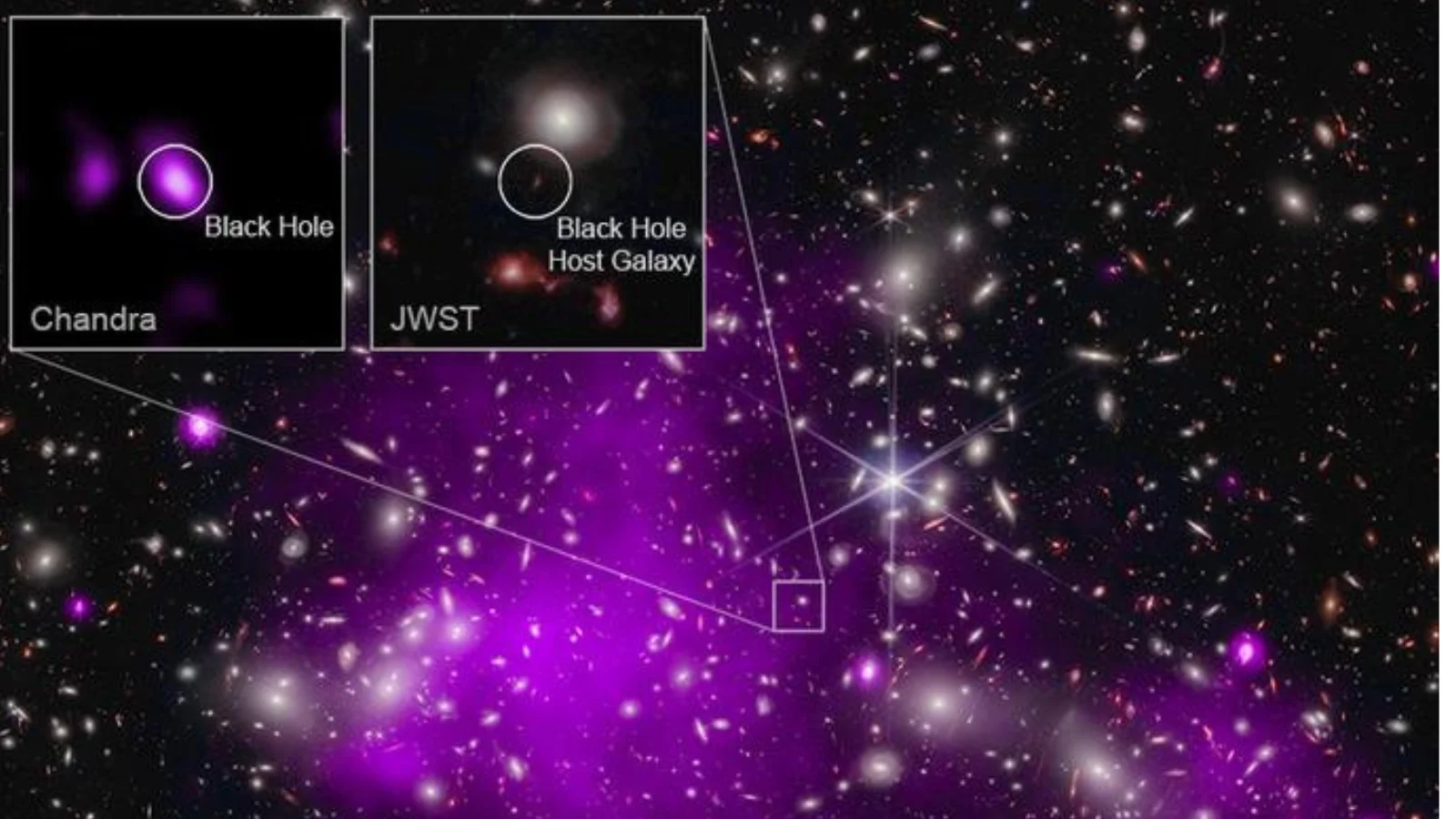

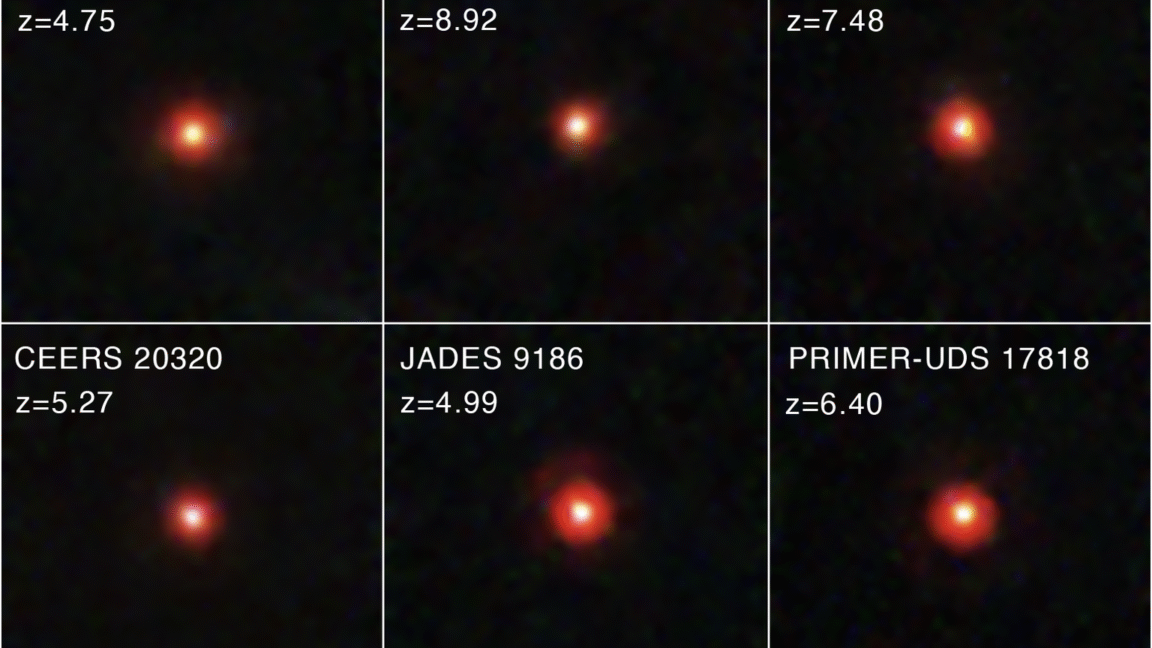

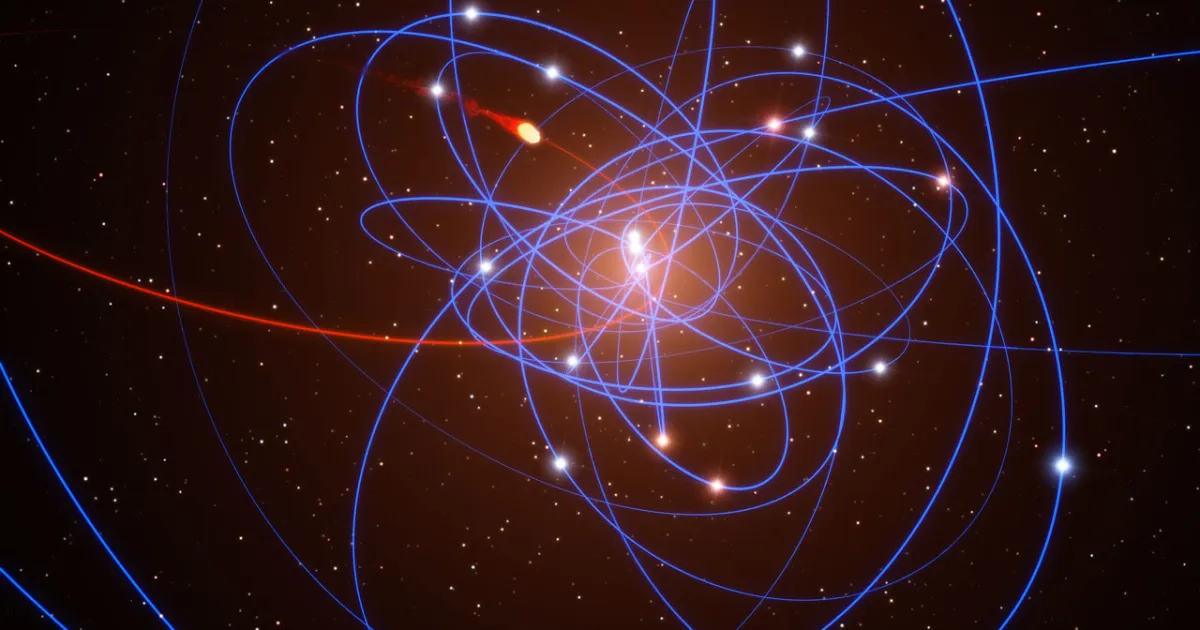

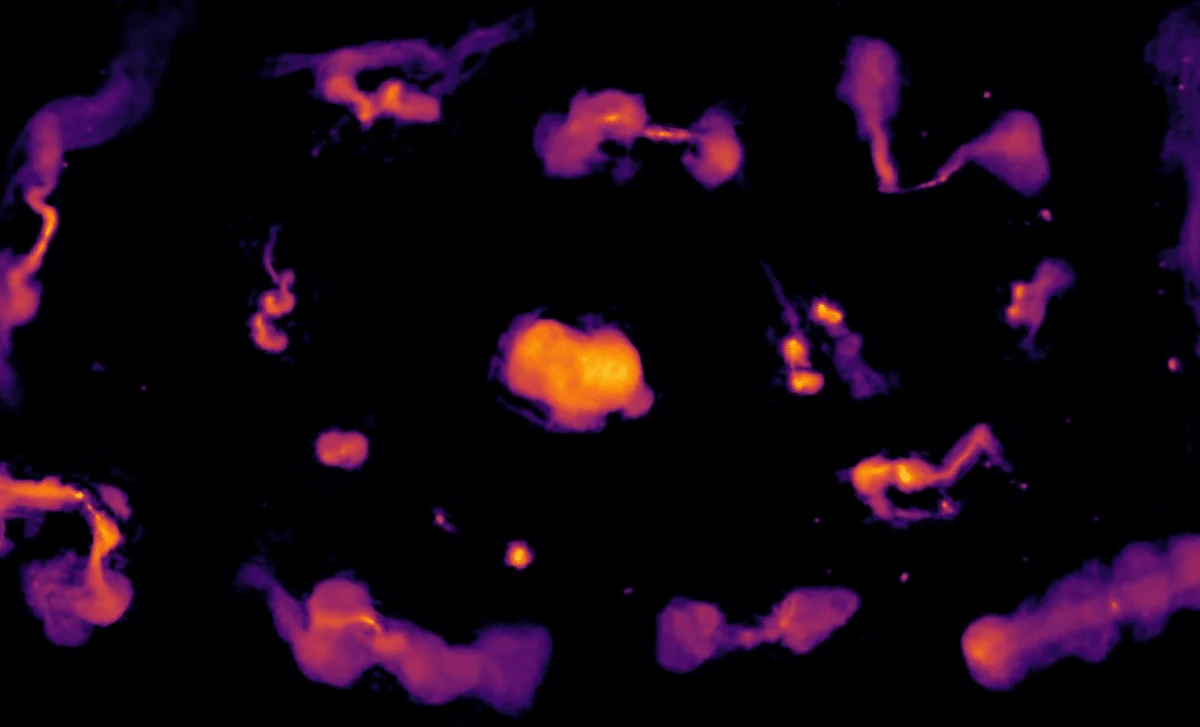

Astronomers released LoTSS-DR3, the most detailed low-frequency radio sky map from the LOFAR network, cataloging 13.7 million cosmic sources and offering new insights into supermassive black holes, their jets, and galaxy clusters, while tackling ionospheric distortions with advanced data-processing techniques on ~18.6 petabytes of data.