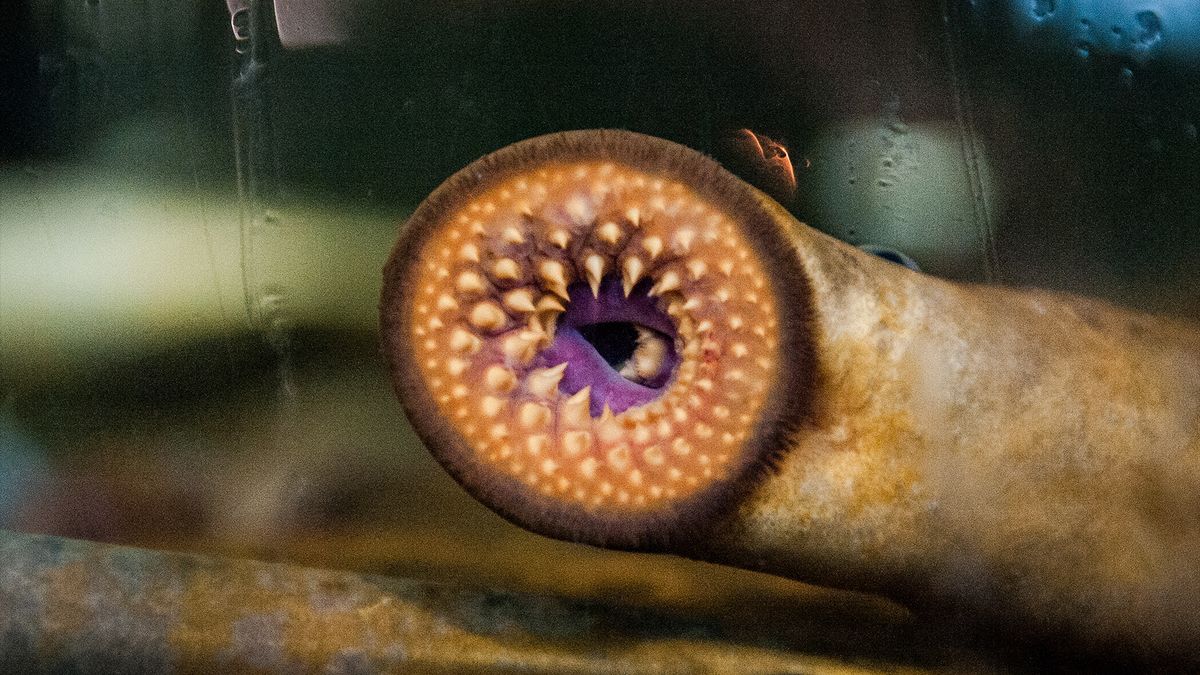

A lone ancestral eye gave rise to vertebrate vision, new theory claims

Researchers from the University of Sussex and Lund University propose that vertebrate eyes did not evolve from early paired eyes but were reinvented from a single central photoreceptive organ after ancestral deuterostomes lost their eyes. This organ supposedly integrated both rhabdomeric and ciliary photoreceptors, with the pineal gland as a remaining link to this history. Published in Current Biology, the hypothesis offers testable predictions but still requires firmer evidence.