Four-Eyed Haikouichthys Expands the Picture of Early Fish—and Their Fear

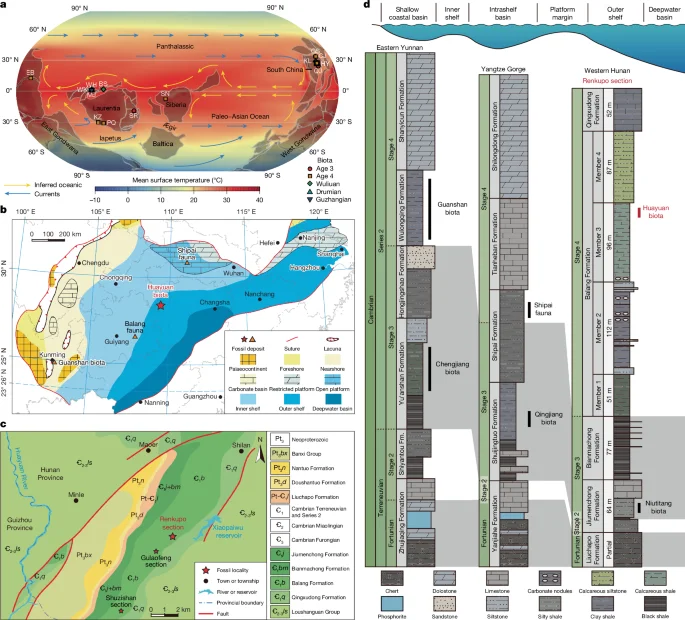

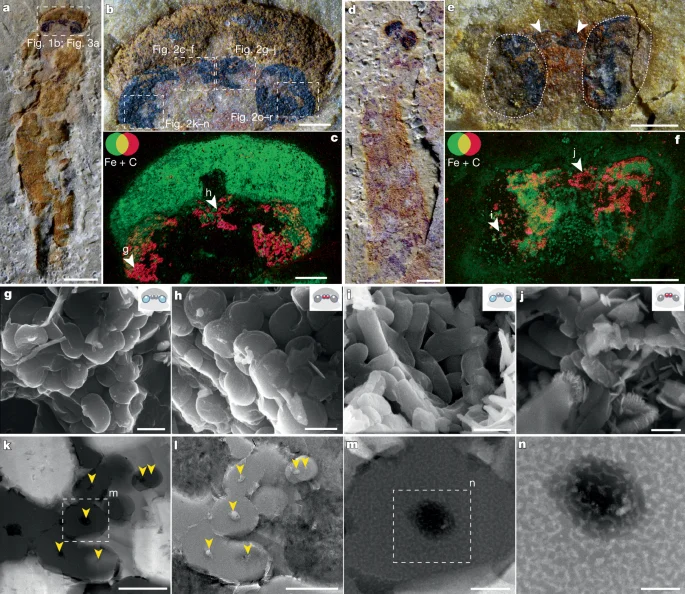

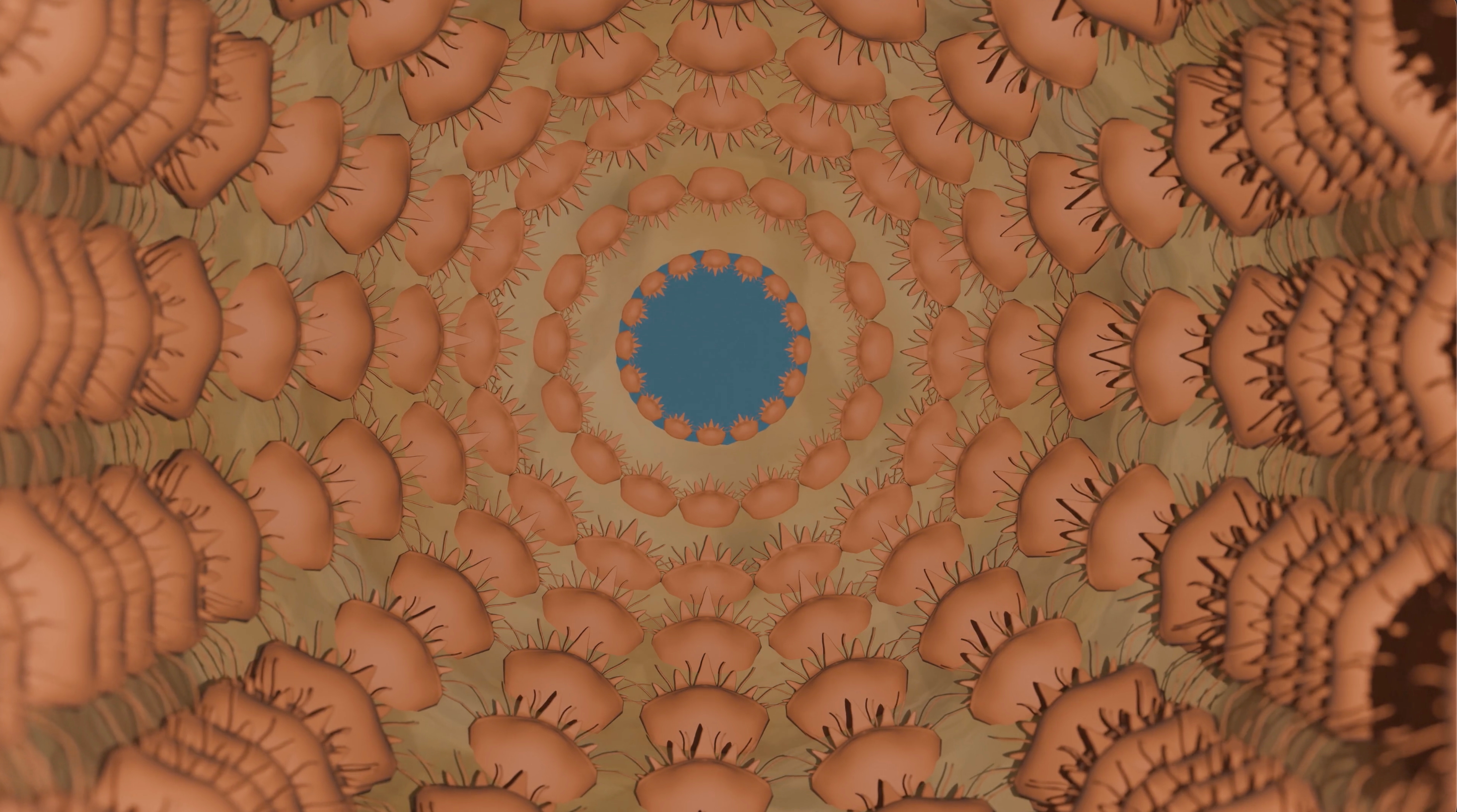

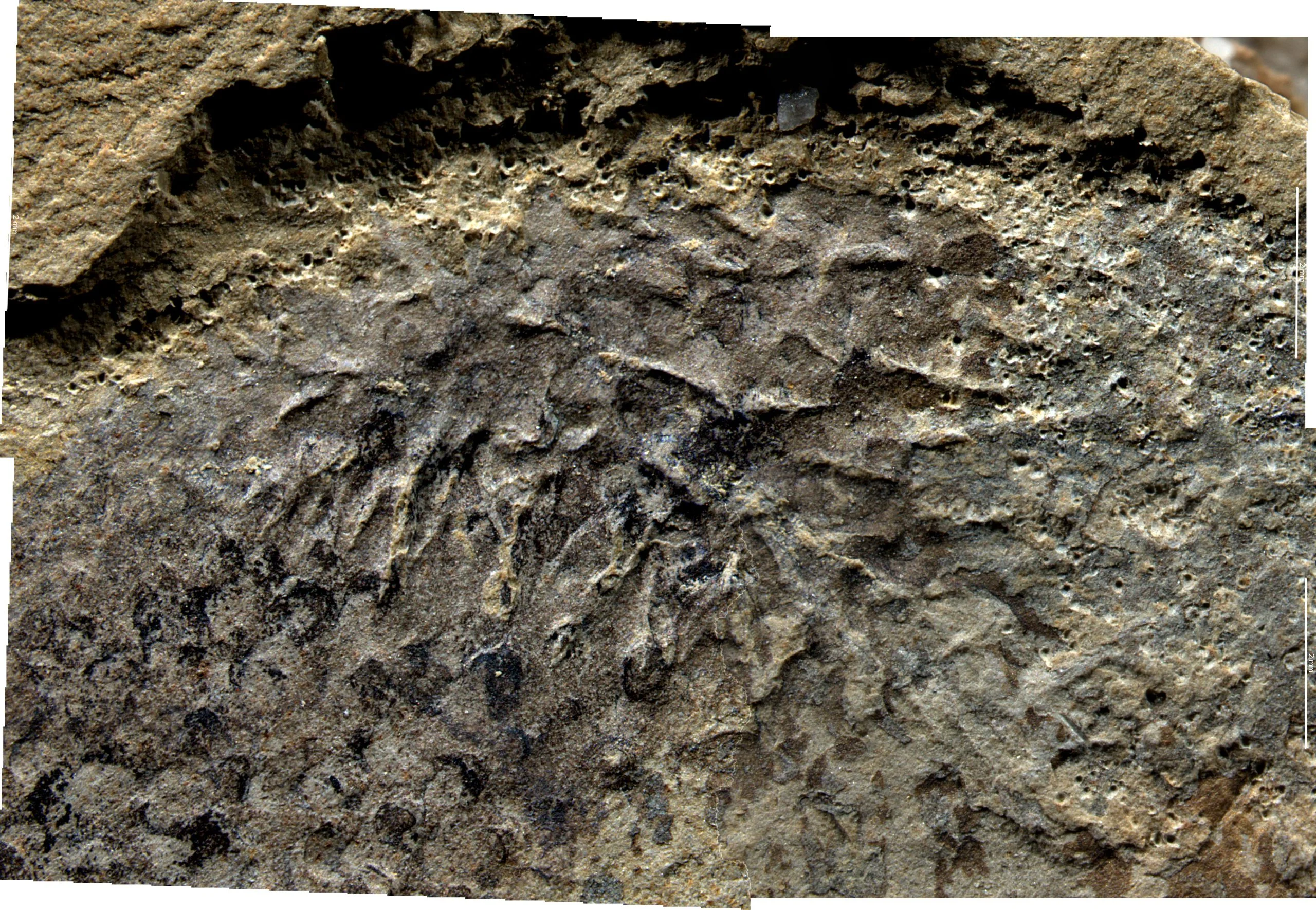

A Nature paper reports that Haikouichthys, an early Cambrian fish from China, had four eyes—two large and two small—giving it a wider field of vision and possibly a pineal-gland precursor. The discovery implies more complex early fish sensory systems than previously thought and feeds a broader discussion about fish sentience and the existential dread of life in a predator-filled ancient ocean.