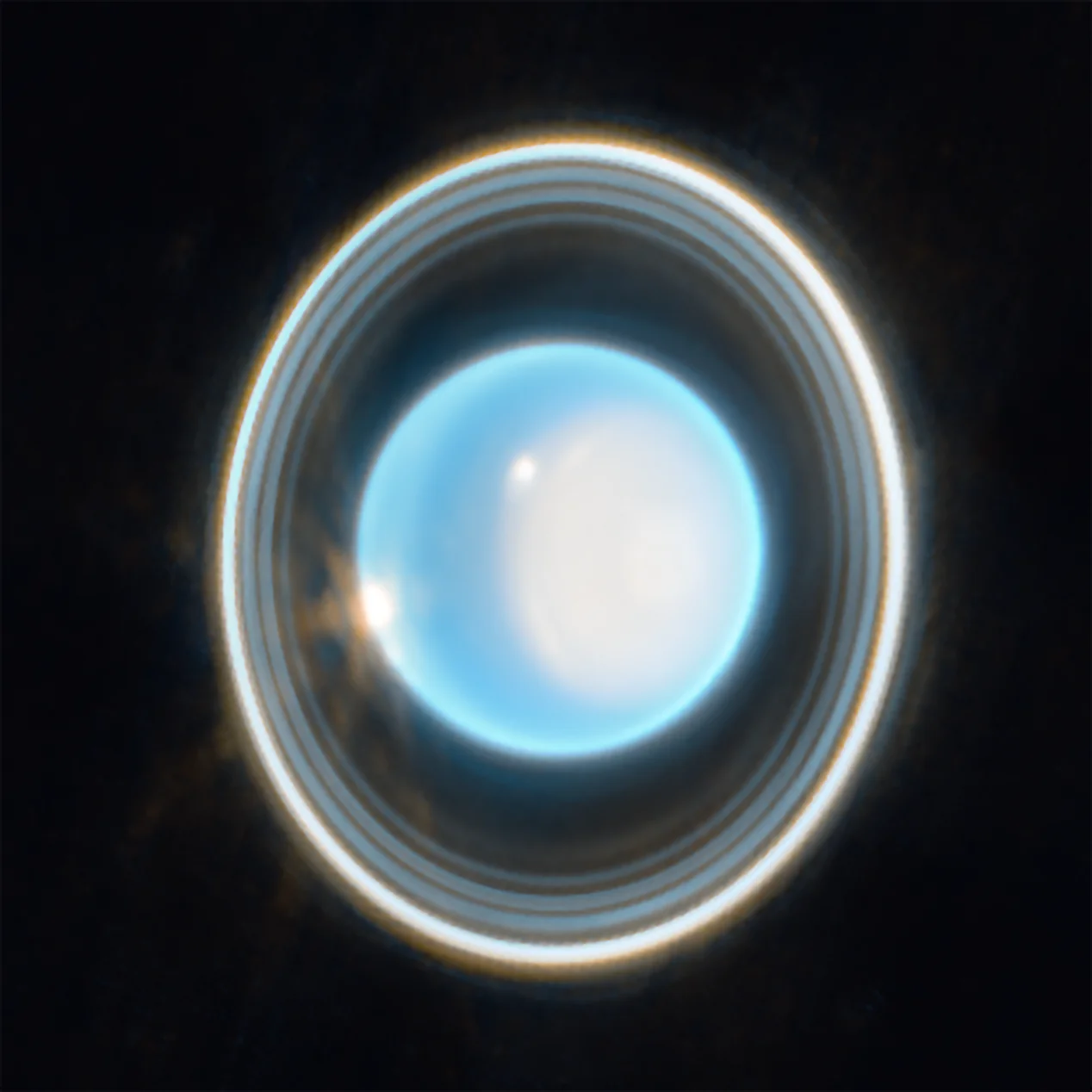

Solar wind storms likely amplified Uranus’ radiation belts during Voyager 2 flyby

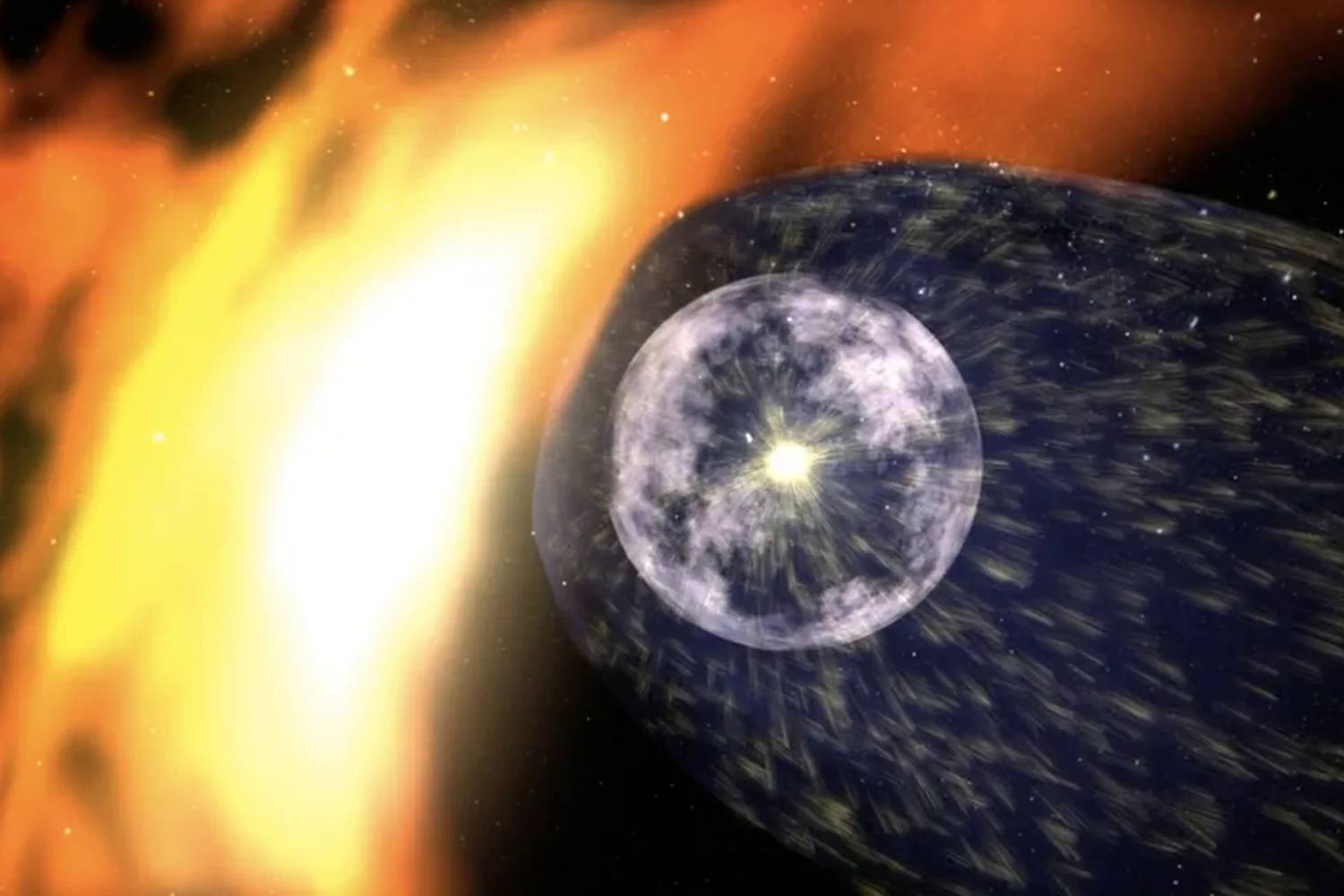

New analysis suggests Voyager 2 encountered Uranus during a solar wind event—likely a co-rotating interaction region—raising Uranus’ radiation belts and solving the long-standing mystery of the intense radiation Voyager 2 saw.