Ancient Asgard archaea may have used oxygen long before Earth’s oxygenation reshaped life

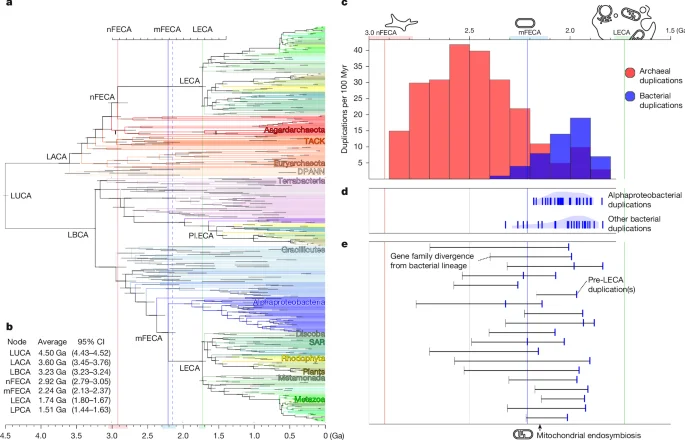

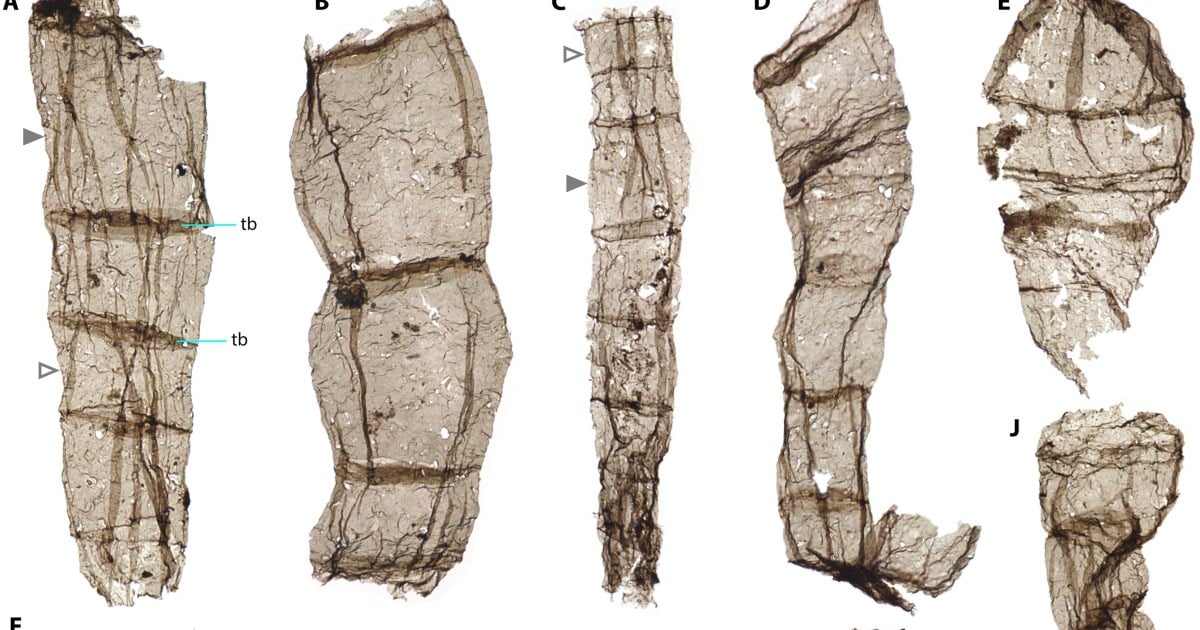

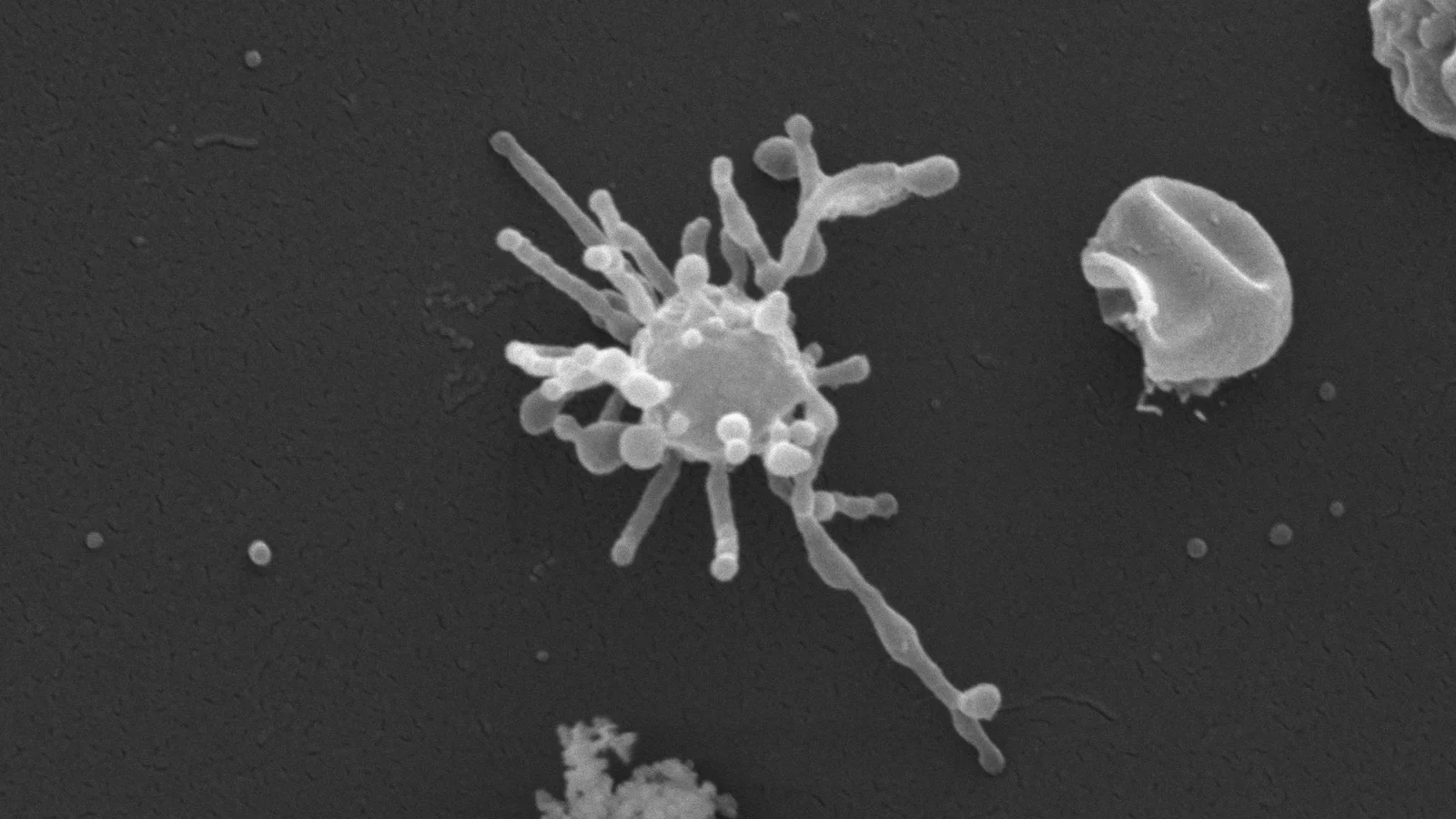

A Nature study analyzing deep-sea sediments found Heimdallarchaeia genomes with components of aerobic respiration, suggesting Asgard archaea could tolerate and potentially use oxygen long before Earth’s oxygenation, providing metabolic groundwork for the archaeal–eukaryotic merger that gave rise to complex life.