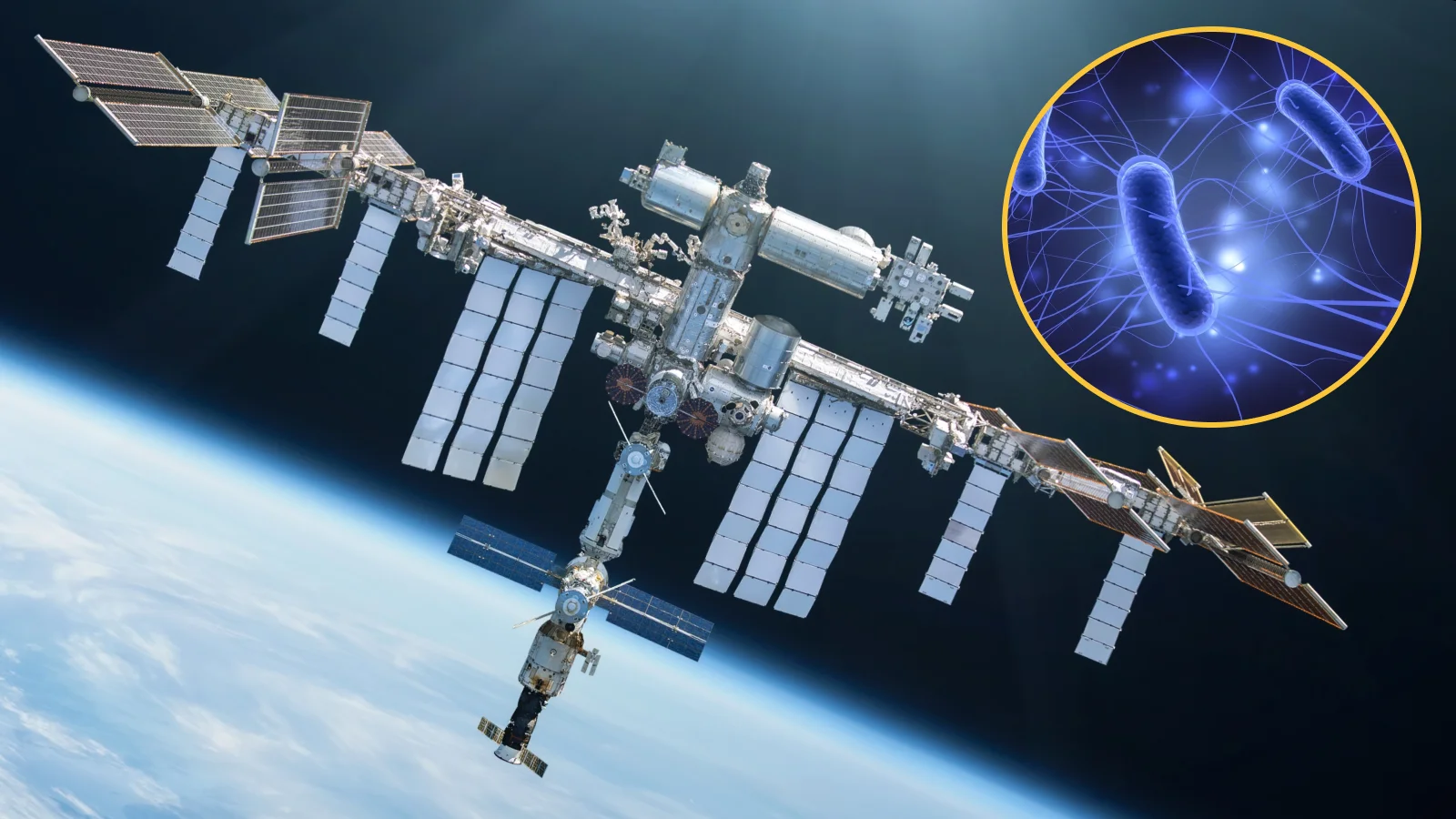

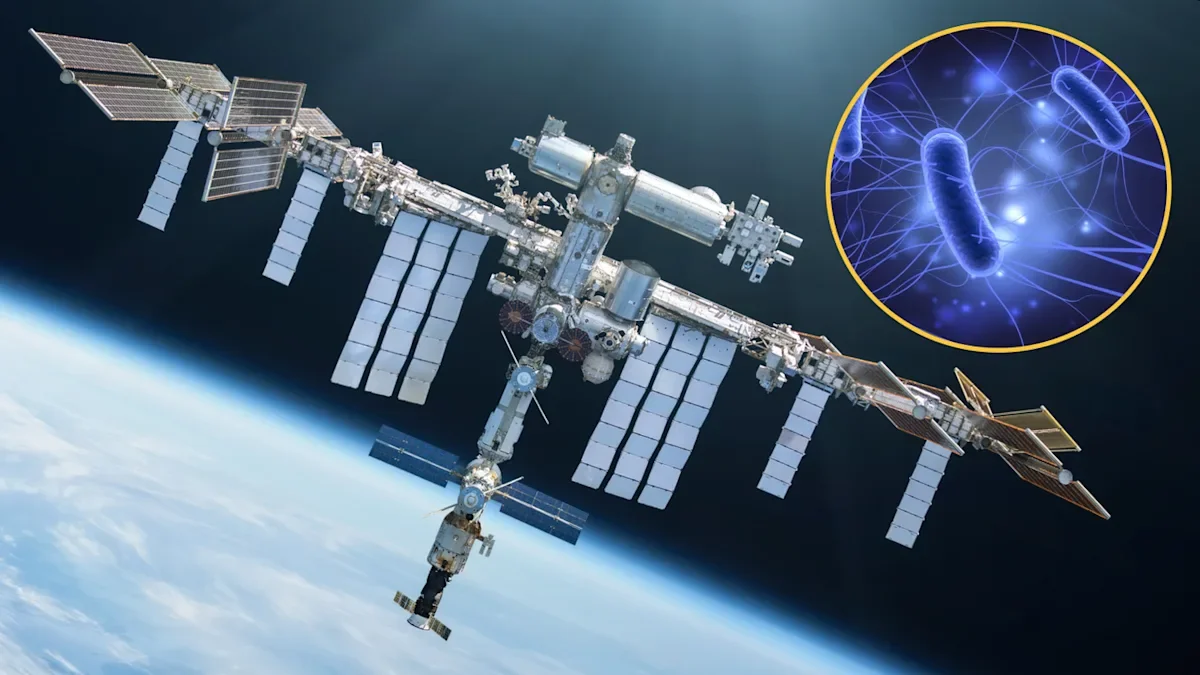

ISS-evolved phages gain edge against Earth bacteria

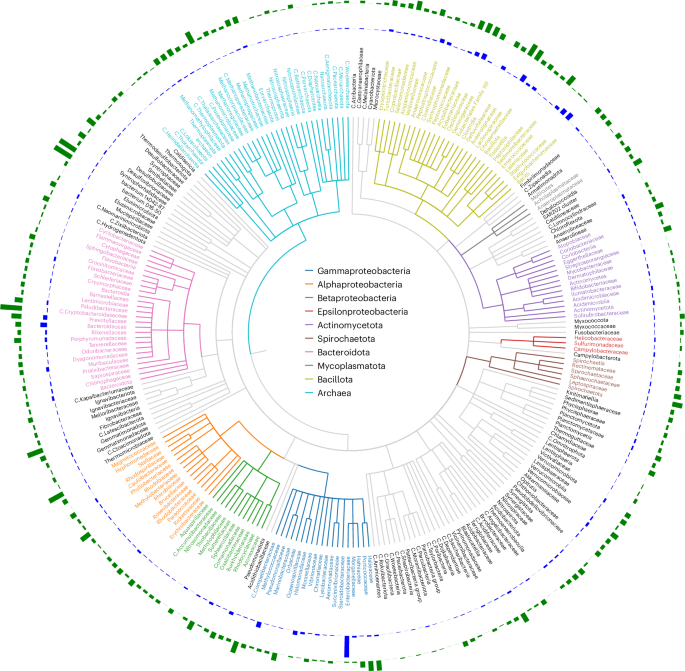

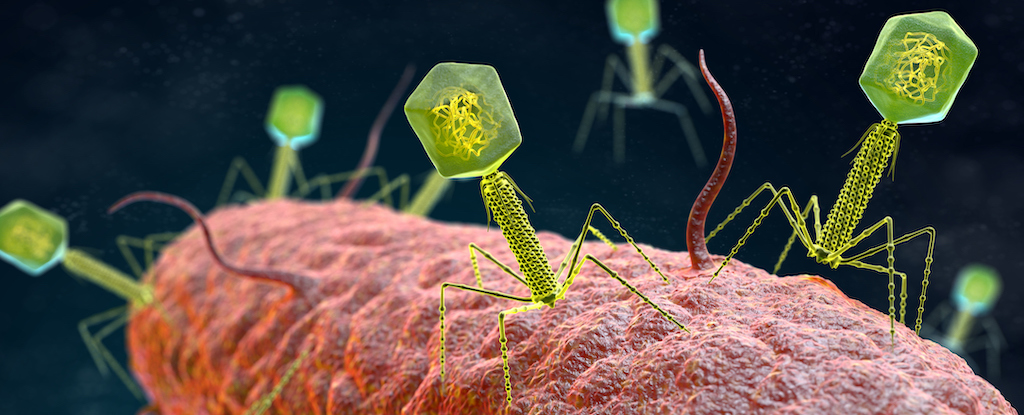

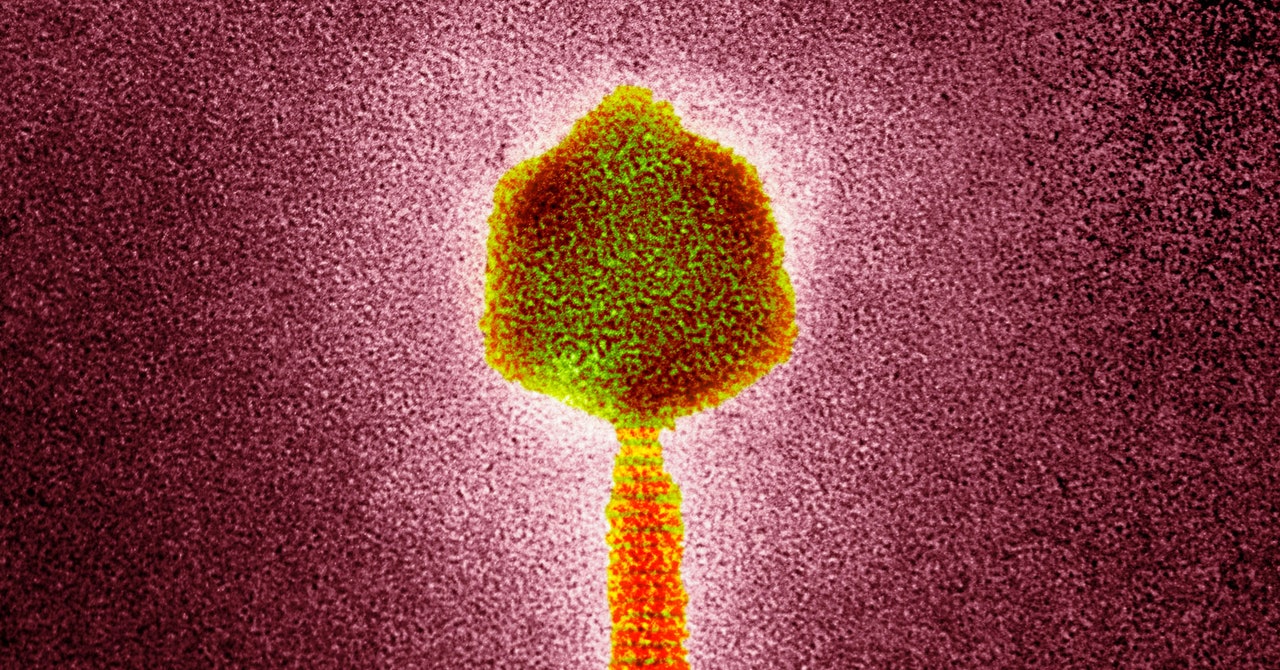

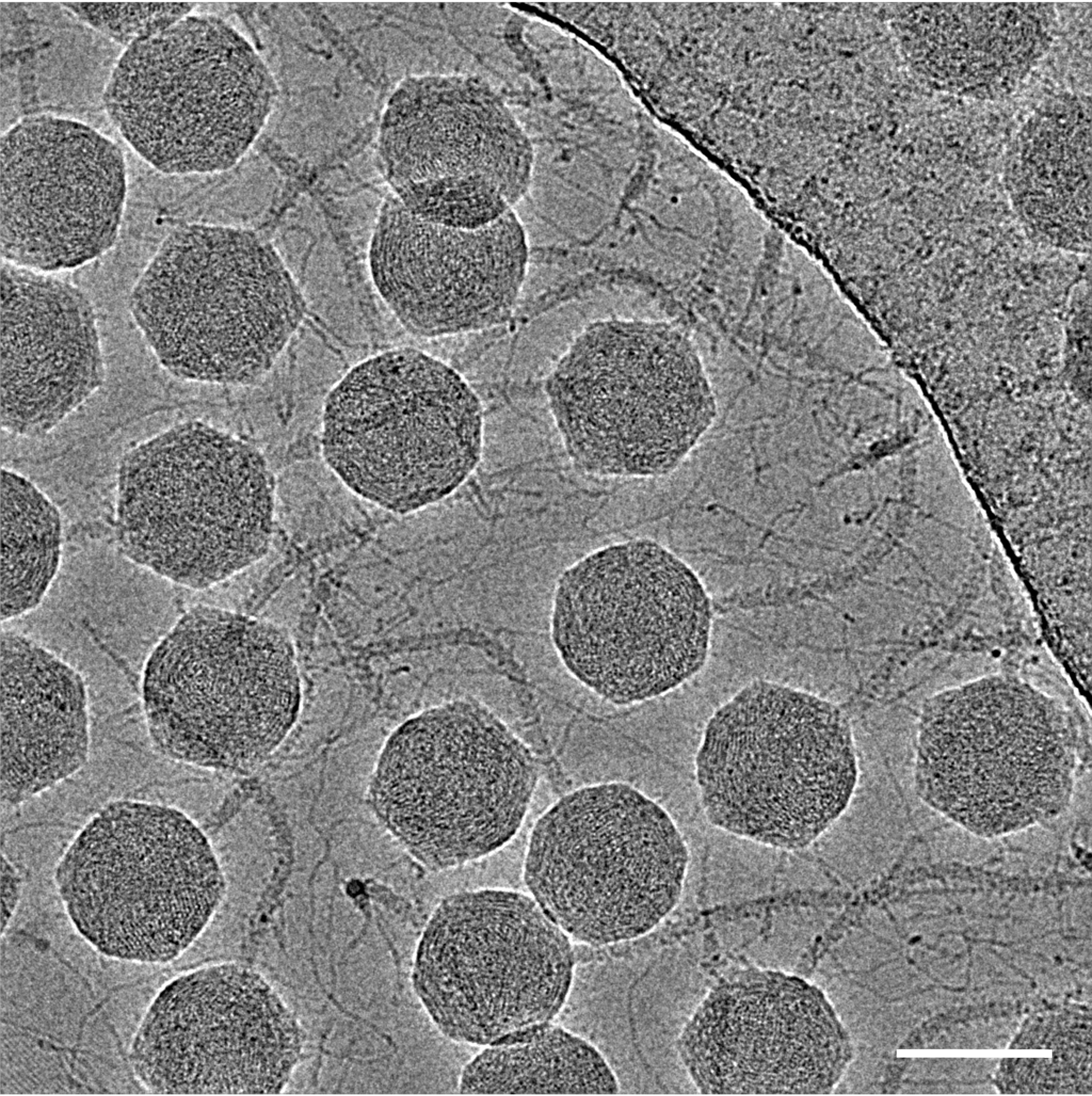

Researchers comparing E. coli infected with the T7 phage aboard the International Space Station to Earth controls found microgravity altered infection dynamics and drove space-exposed bacteria and phages to accumulate distinct mutations. The ISS-evolved phages developed changes in receptor-binding proteins that improved their ability to infect bacteria, and when tested back on Earth they showed increased activity against common urinary tract infection–causing E. coli strains, suggesting space conditions could inform future phage therapies despite practical costs.