Ancient genome reshapes the origin map of syphilis

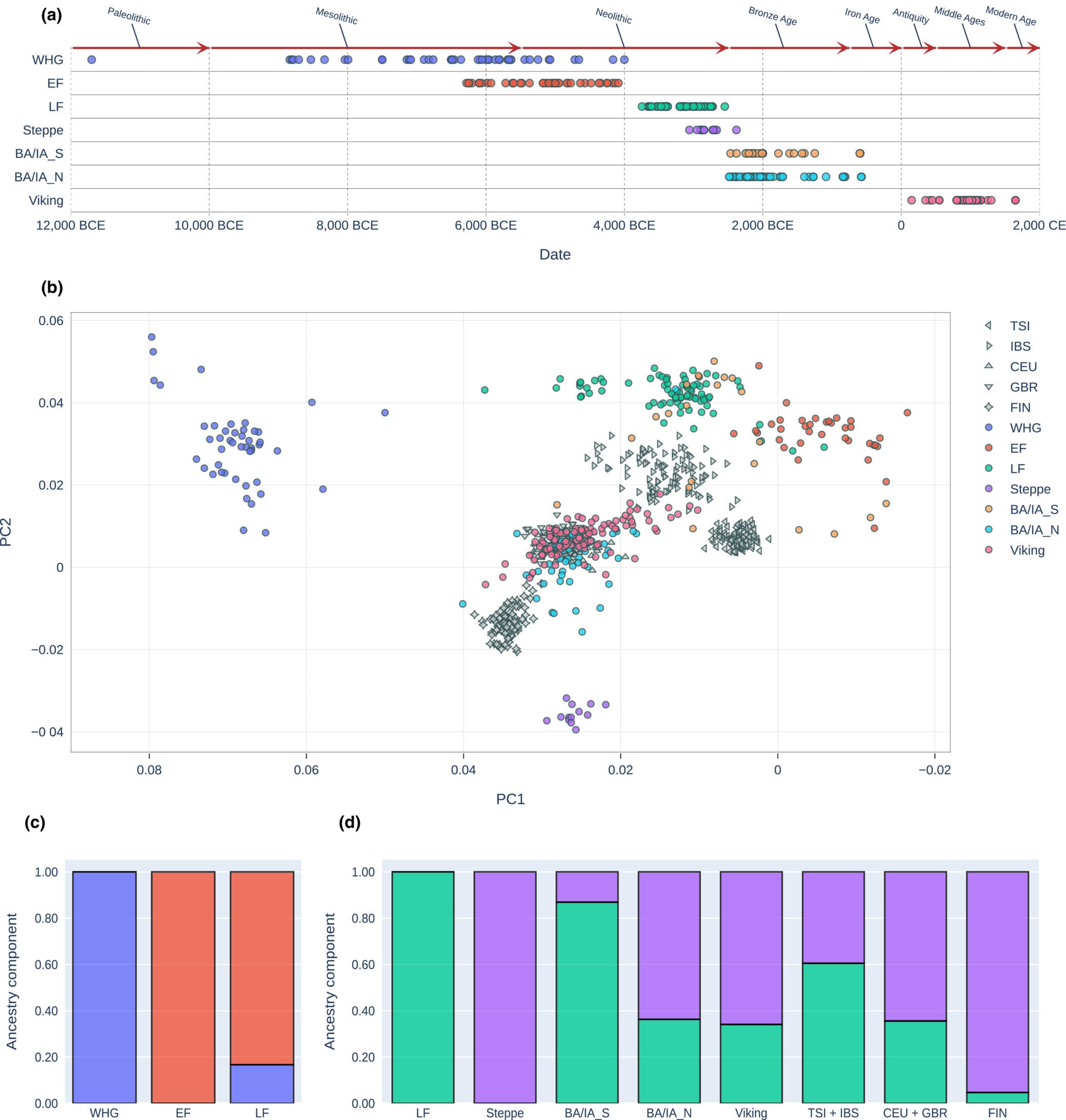

A team analyzing a 5,500-year-old Treponema pallidum genome from a Colombian rock shelter found the pathogen’s lineage was already diverse and not a direct ancestor of modern syphilis, bejel, or yaws. Instead, it’s a sister lineage that diverged around 13,700 years ago, suggesting treponemal diseases spread with ancient humans across continents long before the 1495 Naples outbreak. The discovery challenges single-origin stories and points to a richer, pan-human history of these pathogens, though details about virulence and transmission remain unresolved.