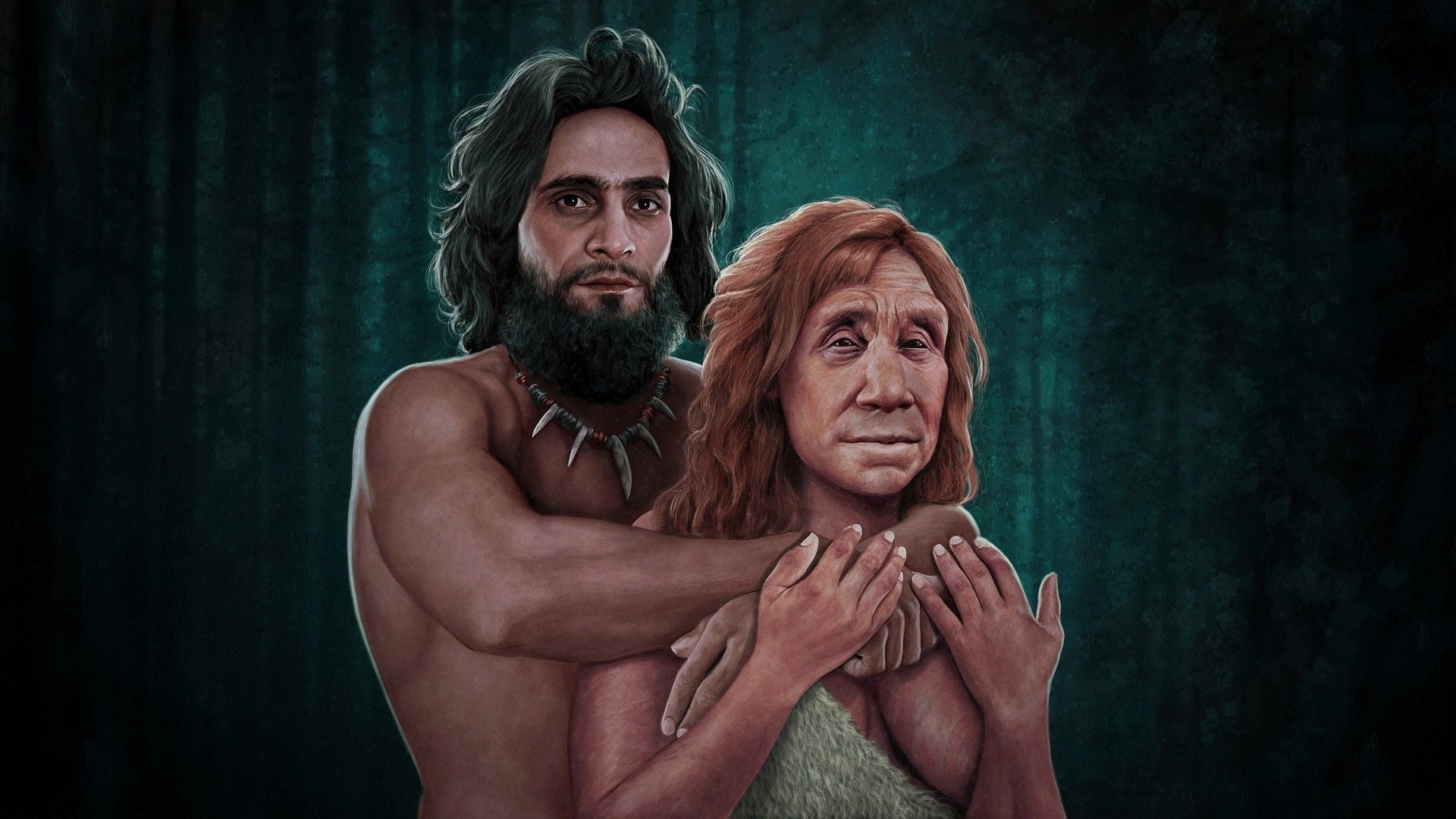

Ancient Neanderthal Men Likely Paired More Often with Early Humans

A study published in Science finds Neanderthal males interbred with human females more often than the reverse, suggesting a non-random partner pattern possibly driven by migration or social dynamics; researchers also note that hybrids from Neanderthal mothers and human fathers may have had lower survival, helping explain the persistence of Neanderthal DNA (up to about 2%) in modern European and Asian populations.