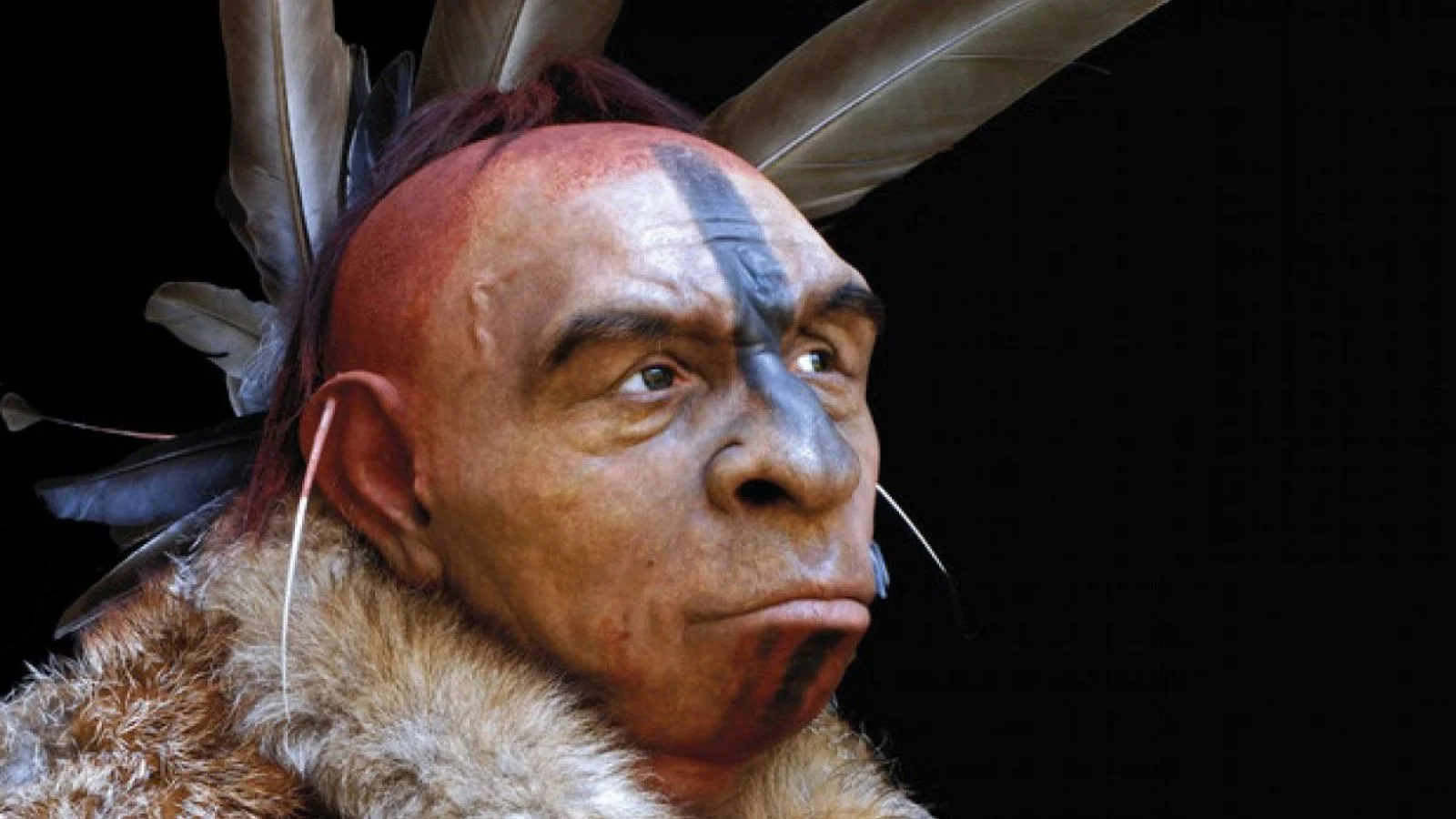

Neanderthals fell to a mosaic of factors, not a single foe

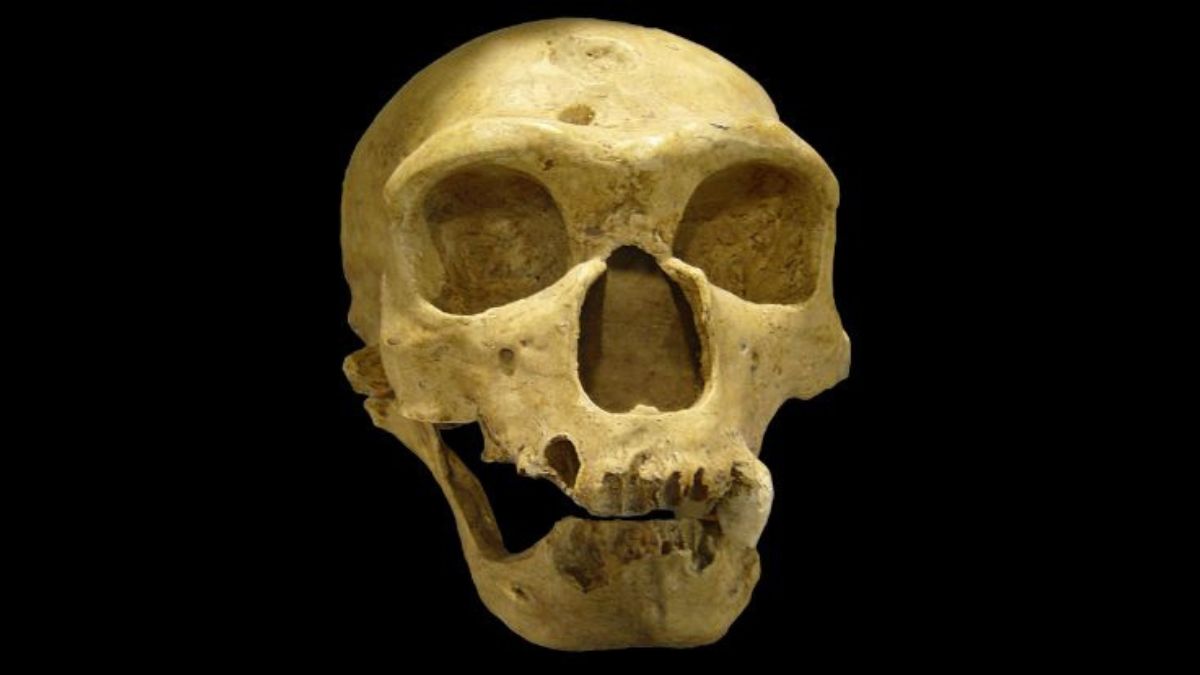

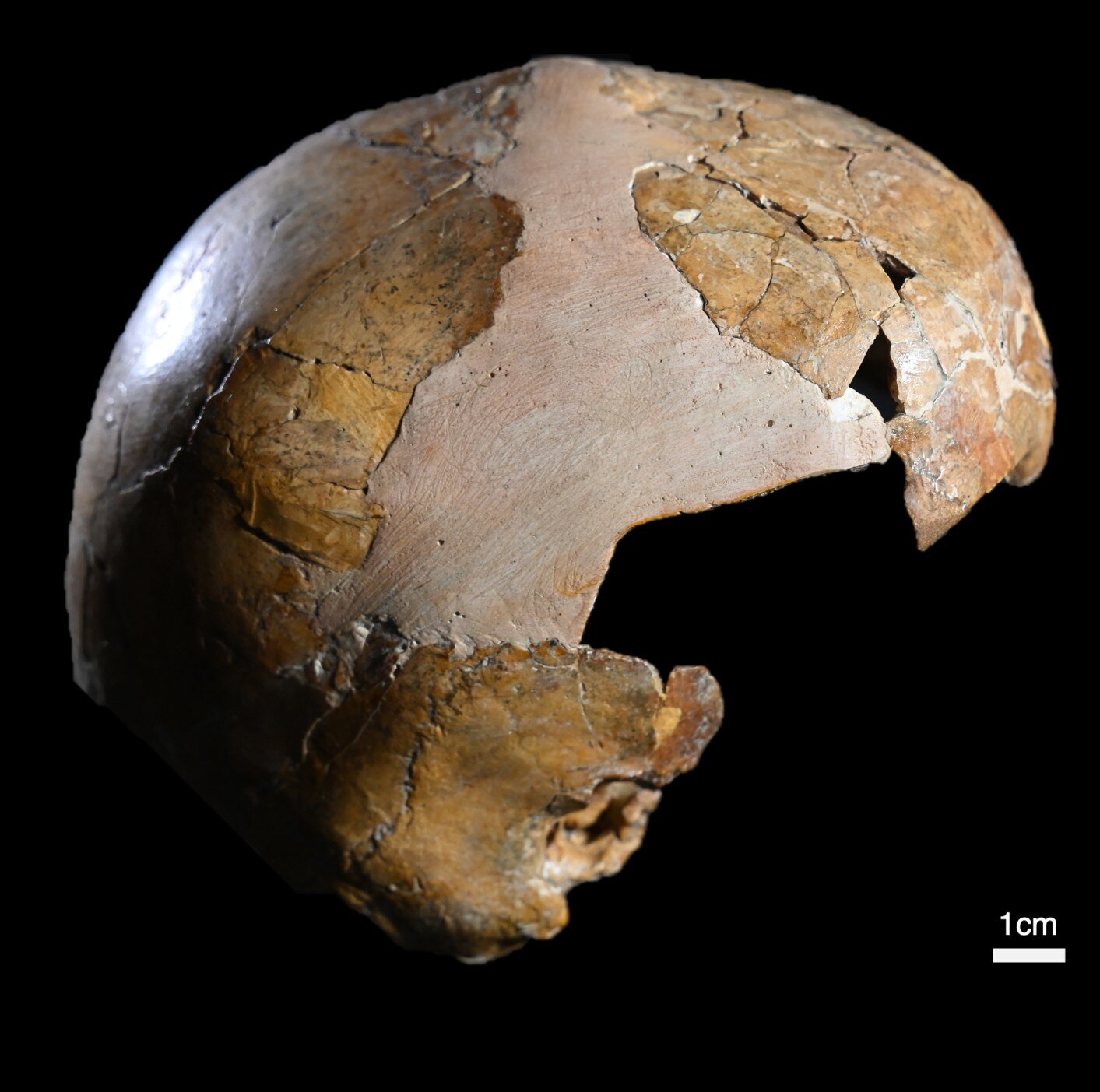

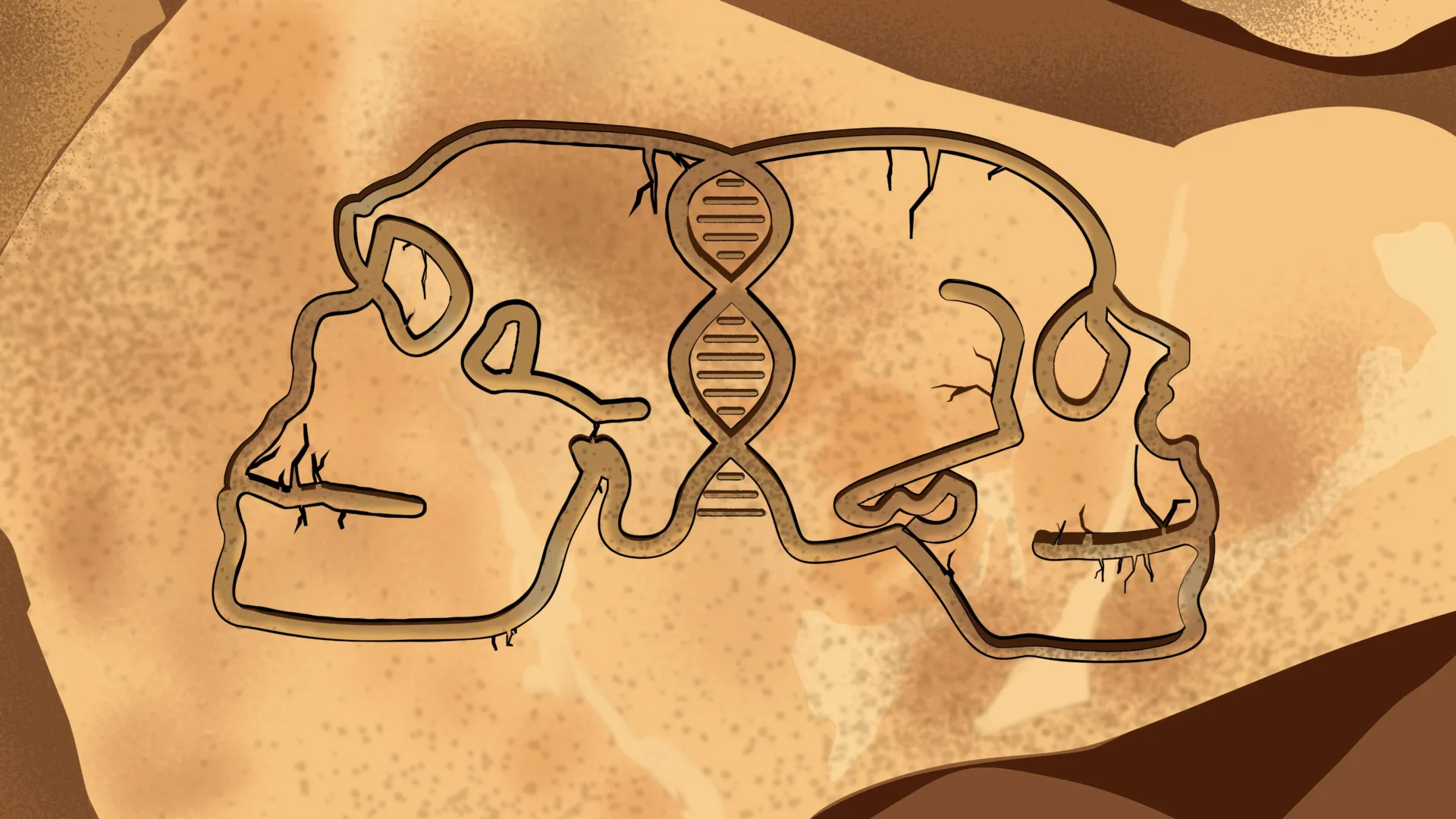

Extinction of Neanderthals appears to be the result of a mix of regional pressures: small, isolated populations prone to inbreeding and mutational burden, competition with expanding modern humans, and varied demographic dynamics across Eurasia. Genetic evidence confirms interbreeding with Homo sapiens, meaning Neanderthals contributed to the modern human genome, but there is no single smoking gun or uniform fate—different Neanderthal groups disappeared for different reasons over time.