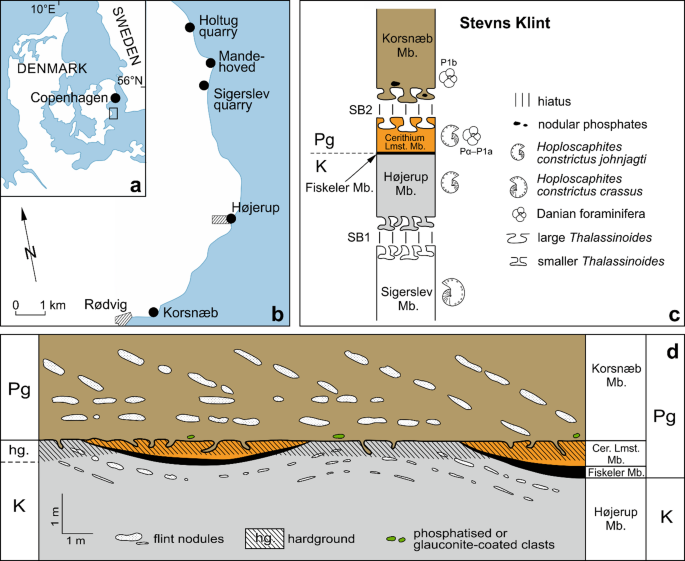

Ammonite Survival Across the Cretaceous–Paleogene Boundary Confirmed in Denmark

New data from Denmark confirm that some ammonite populations survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, with evidence suggesting both survival and redeposition depending on the microfacies and stratigraphic context, supporting the hypothesis that certain ammonites persisted into the Danian period.