Mathematical Model Suggests Genetic Dilution Led to Neanderthal Extinction

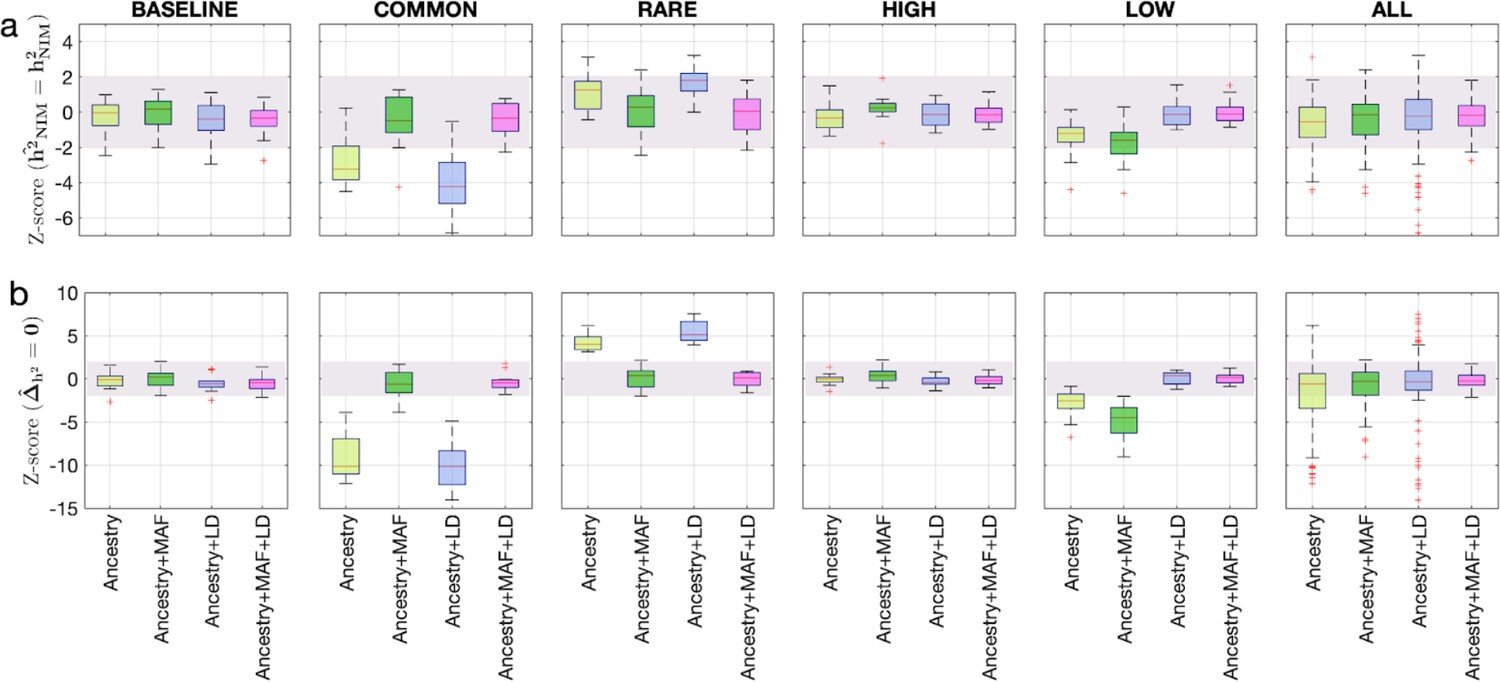

A new study using a mathematical model suggests that the disappearance of Neanderthals could be explained solely by genetic dilution resulting from repeated small-scale interbreeding with modern humans over thousands of years, without the need for catastrophic events.