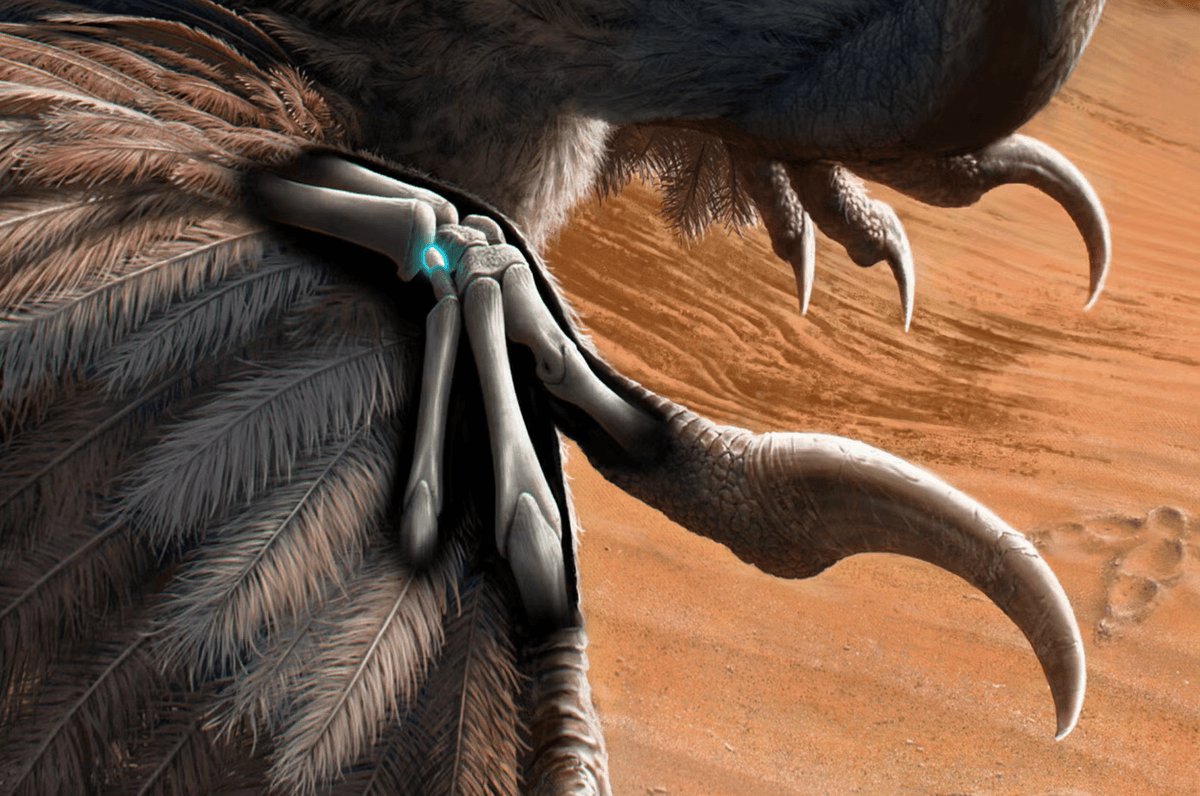

Archaeopteryx reveals hidden mouth features linked to the dawn of avian flight

A Field Museum study of Archaeopteryx fossils uncovers previously unseen skull features—an indicator bone for a highly mobile tongue, soft-tissue traces interpreted as oral papillae on the roof of the mouth, and jaw-tip openings suggesting an early bill-tip organ. These traits, common in living birds but absent in nonflying dinosaurs, may have helped feeding and food processing as flight evolved, implying they appeared around the origin of birds in the Late Jurassic. Archaeopteryx likely represents an early feathered flyer rather than a direct ancestor of modern birds.