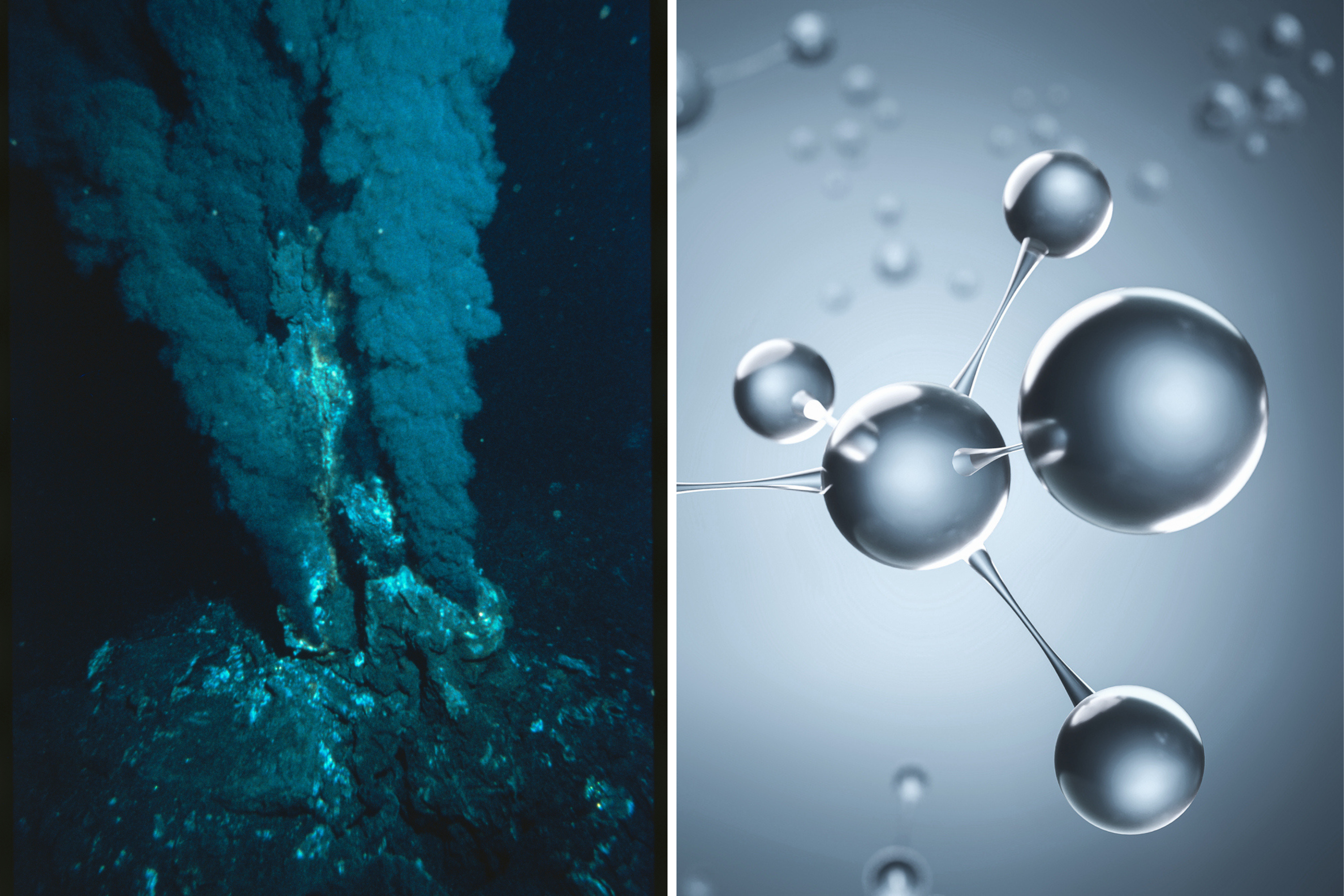

Origins Reimagined: Life May Have Begun in a Primordial Gel

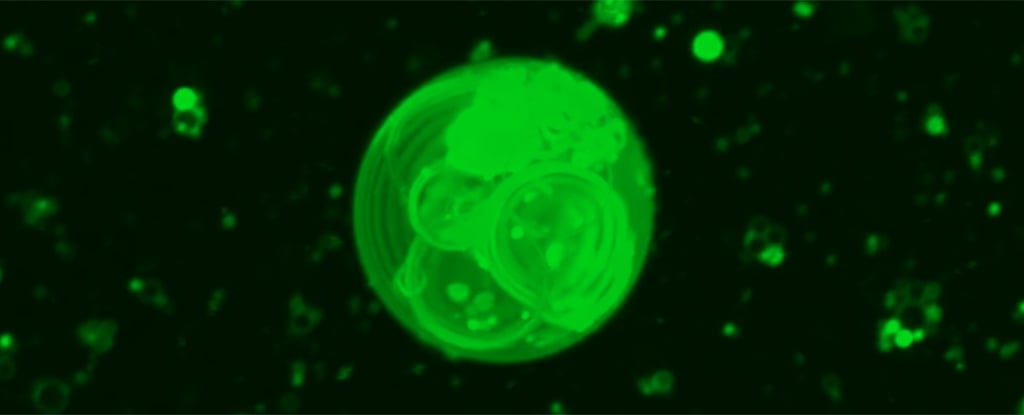

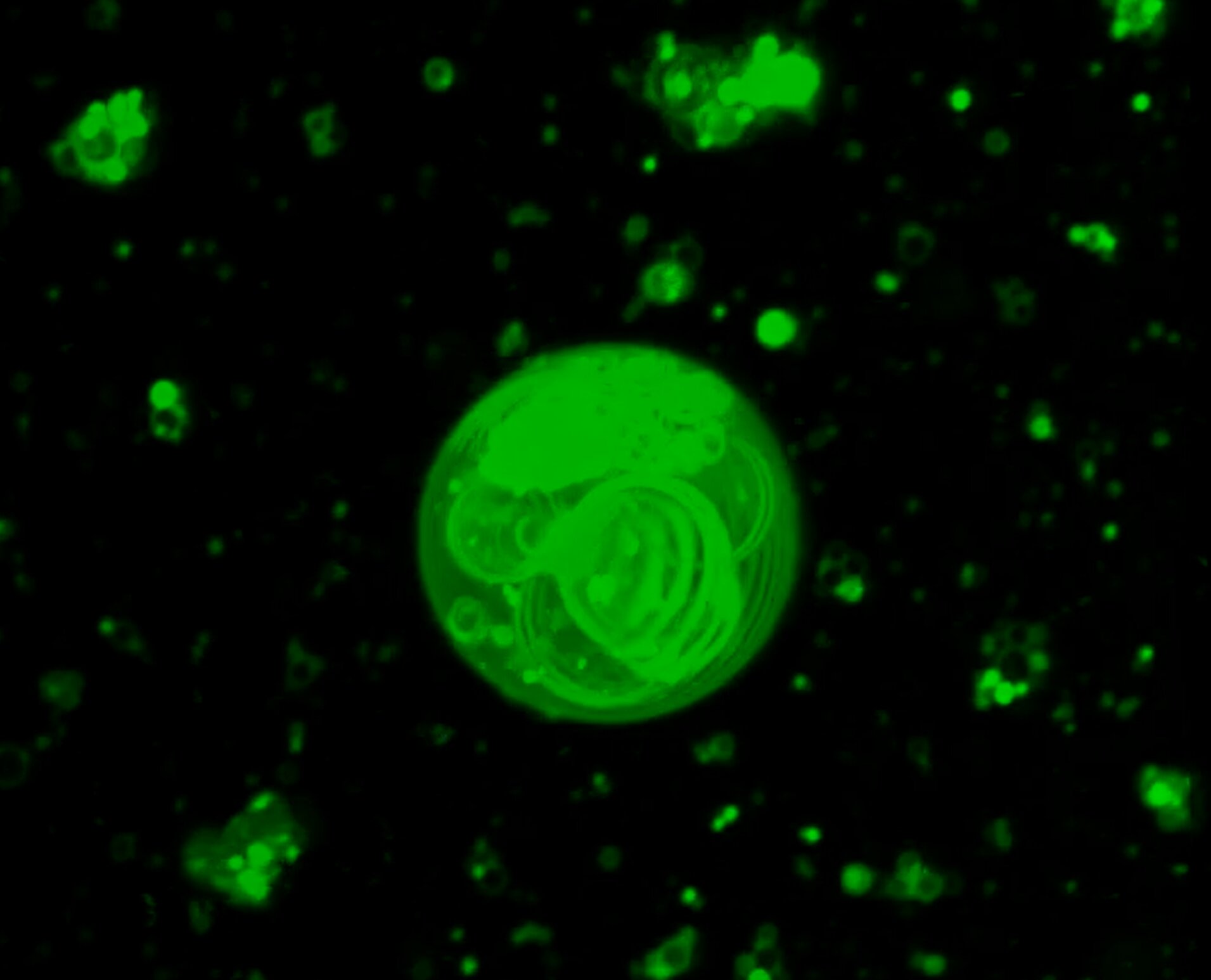

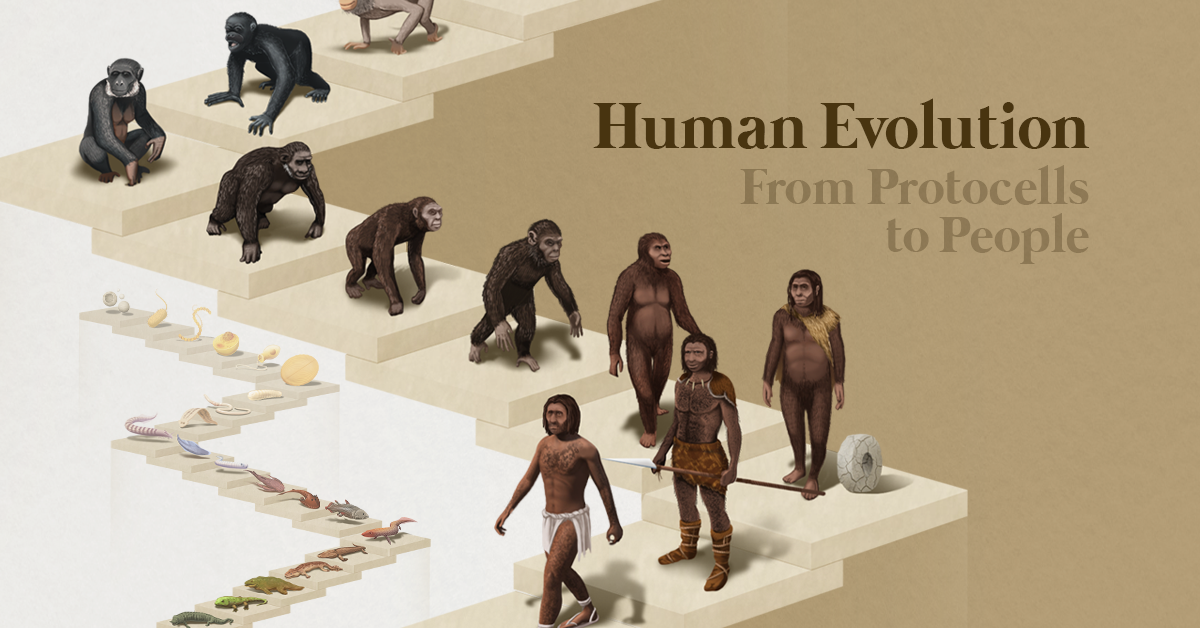

Researchers propose that life began in prebiotic gels—soft, structured matrices on early Earth that fostered chemical evolution toward protocells, via either phase separation or proto-films, within a protective, biofilm-like environment that shielded and shared resources. This gel-first view broadens the search for alien life to gel-based structures and challenges the traditional cell-first narrative.