What Non-Genetic Cells Reveal About Life and Death

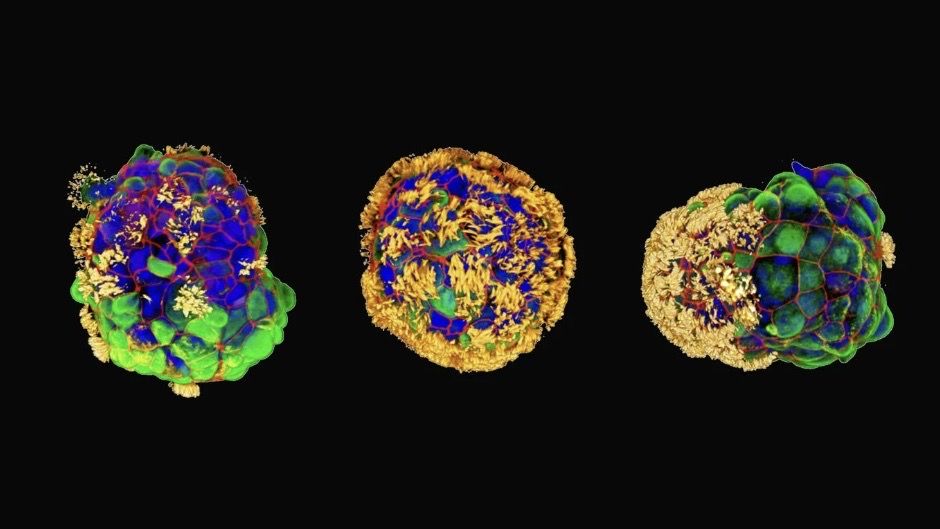

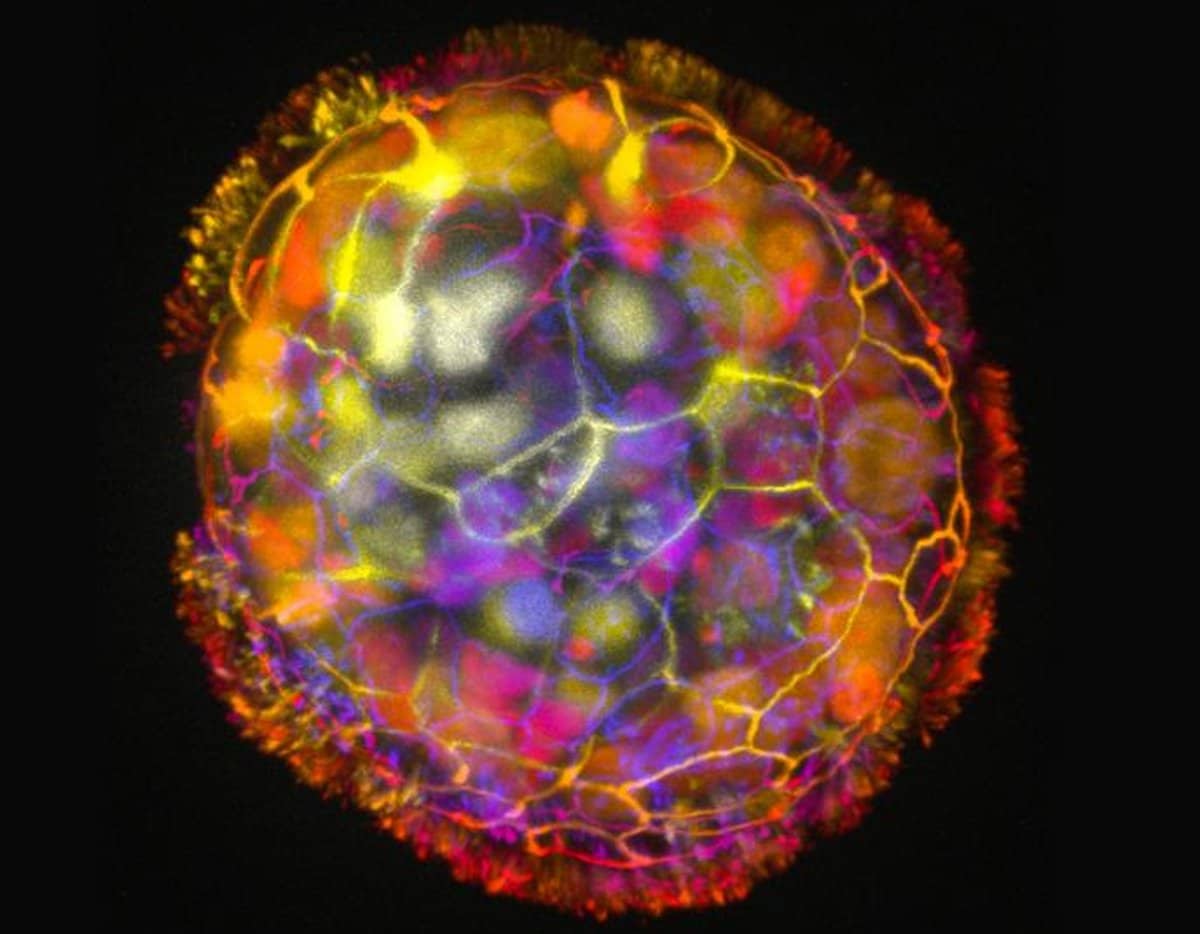

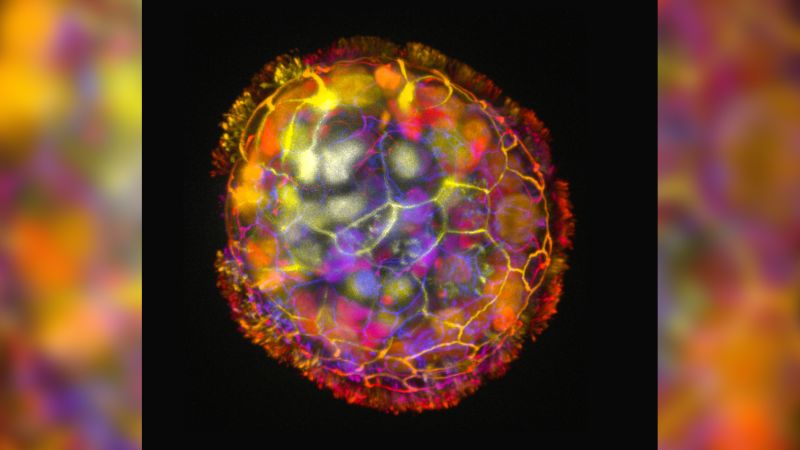

The article explores microchimerism, the presence of non-self cells within the human body, which are transferred between mother and child during pregnancy, challenging traditional views of human identity and immune response, and revealing potential implications for health and science.