New African Fossils Reveal Secrets of Earth's Largest Mass Extinction

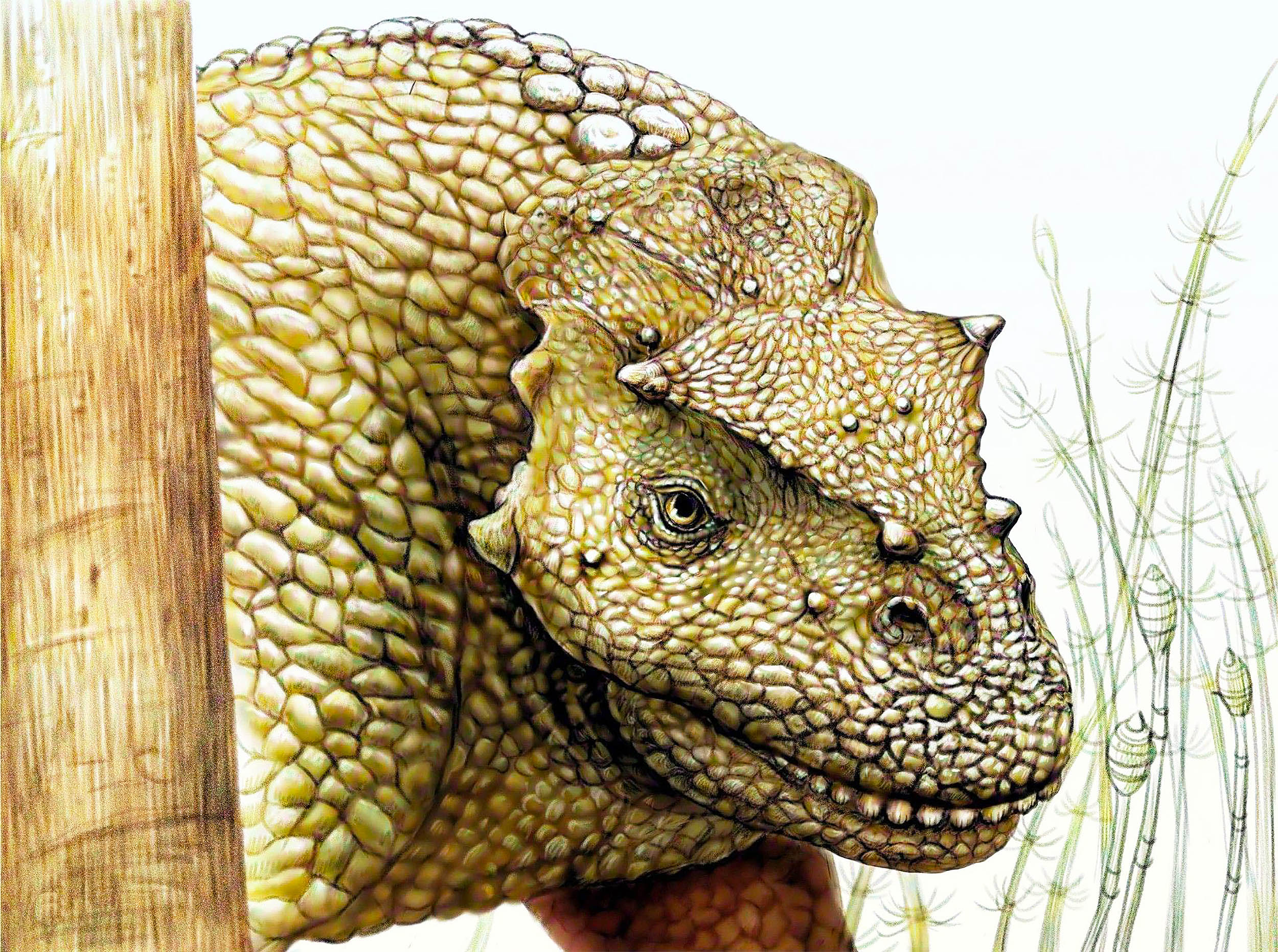

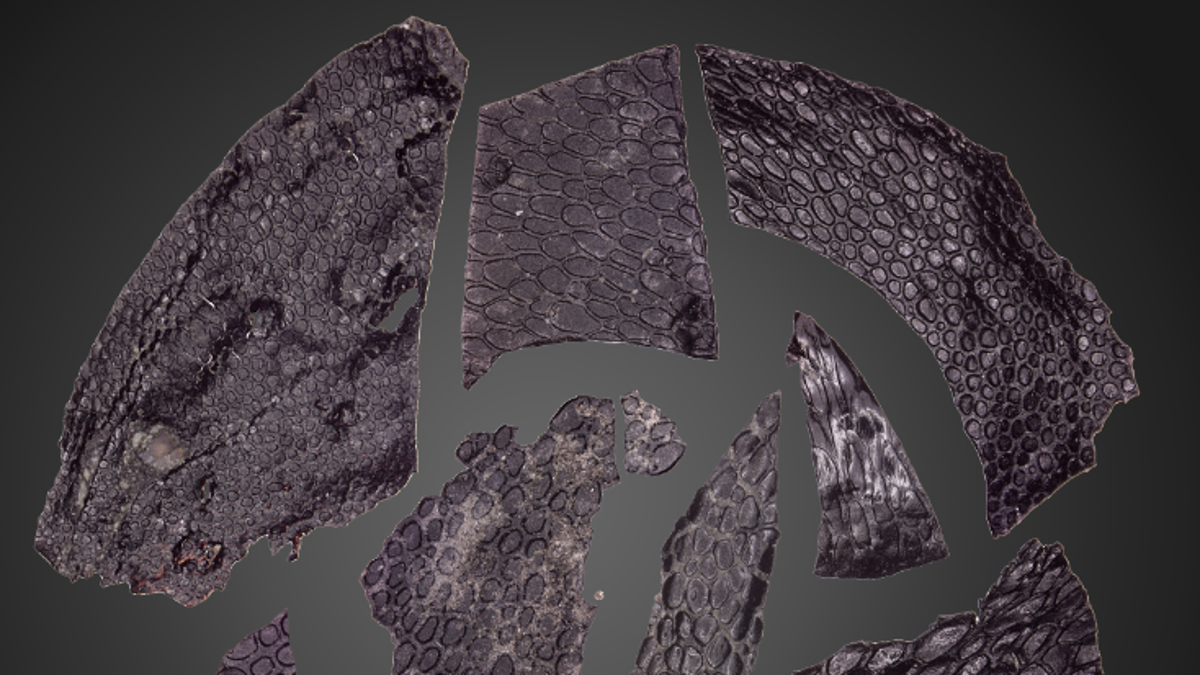

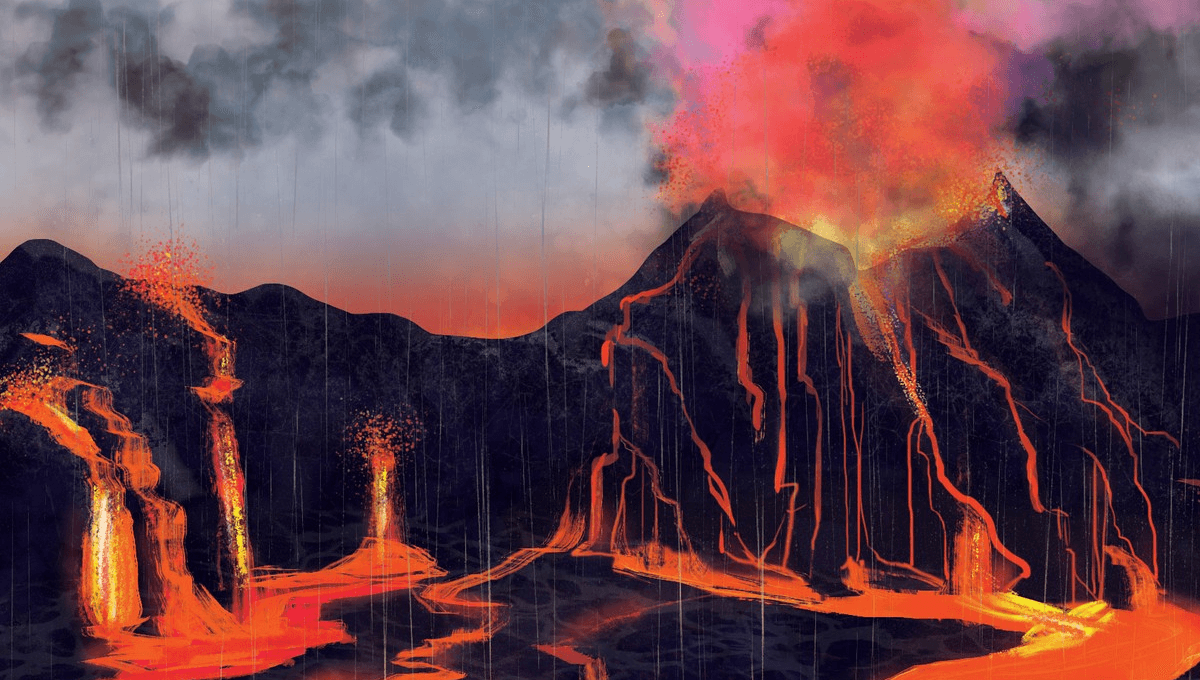

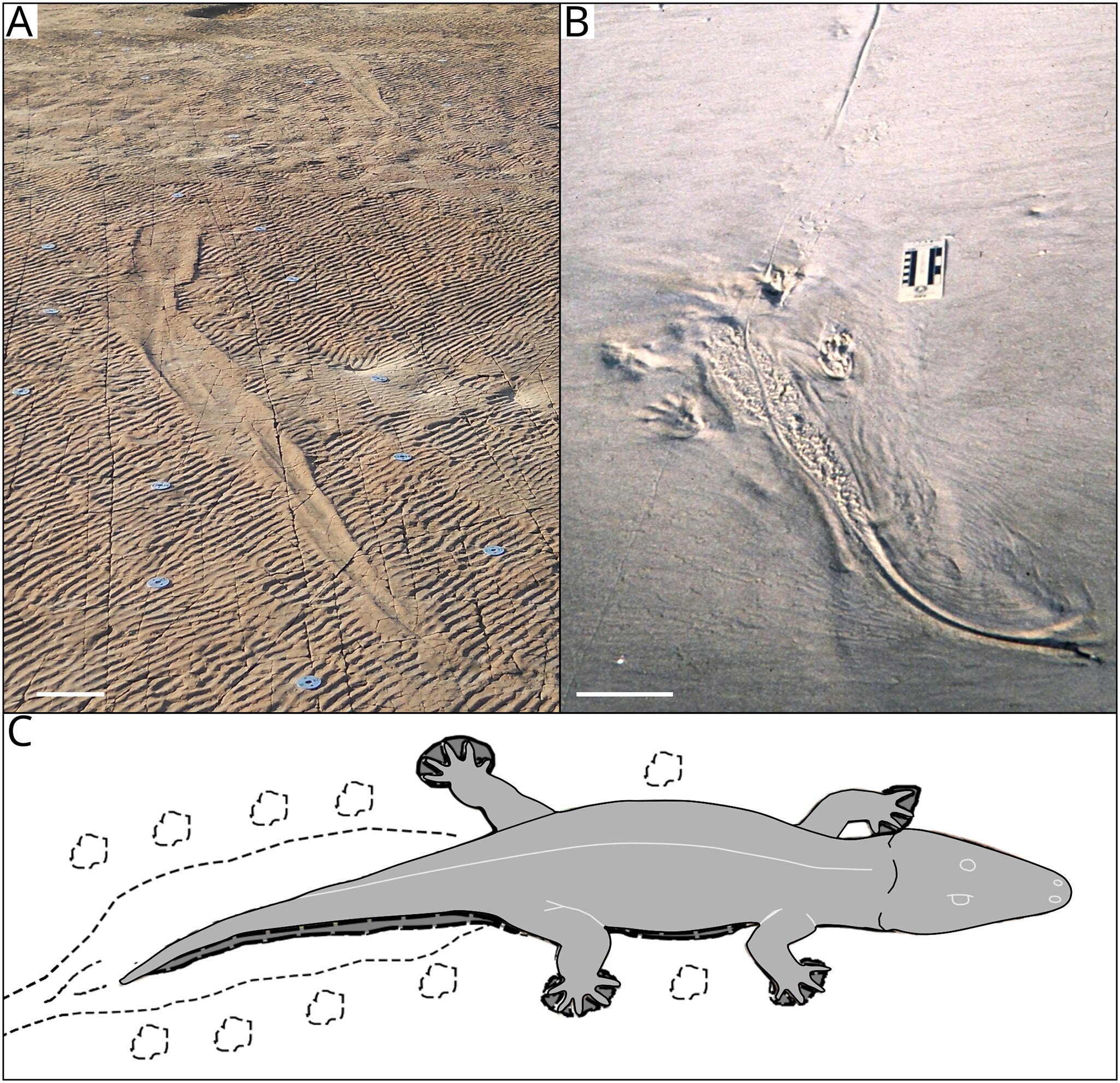

Scientists have uncovered detailed fossils from southern Africa that reveal the rich ecosystems just before Earth's largest mass extinction at the end of the Permian period, providing new insights into which species thrived and which vanished, and offering a broader understanding of global extinction patterns.