Starfish Walks: Decentralized, Brain-Free Locomotion with Hundreds of Feet

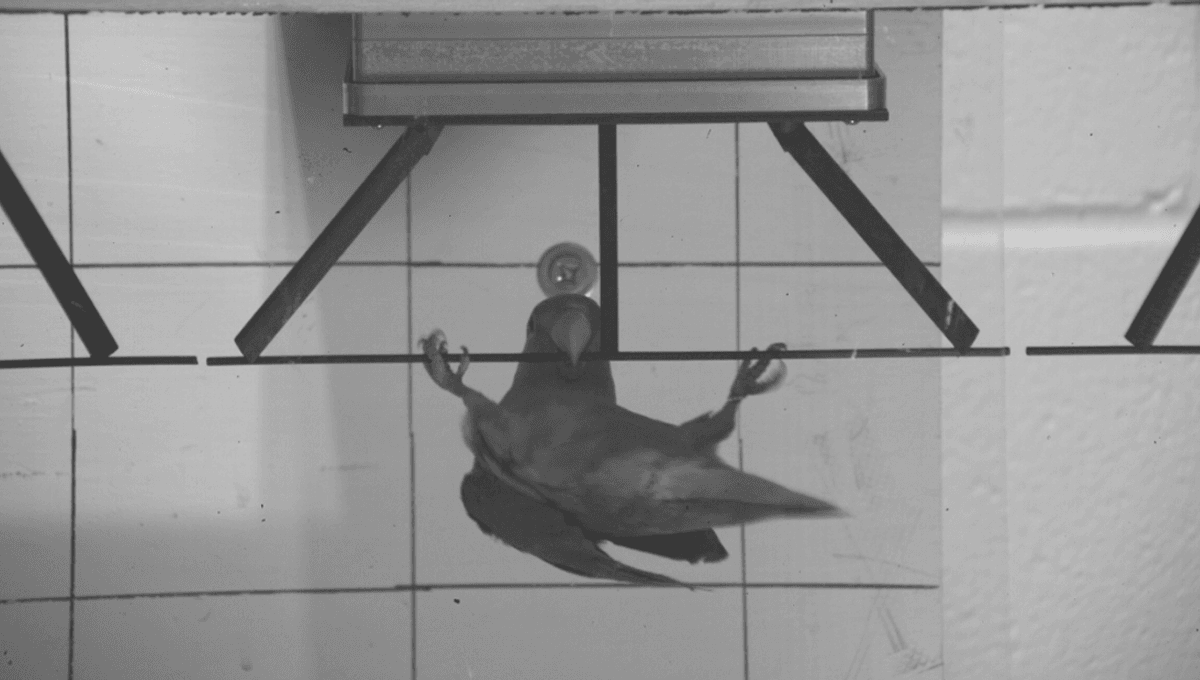

Sea stars crawl using hundreds of tube feet coordinated by local foot–surface interactions rather than a central brain. By adjusting how long each foot stays adhered, they modulate gait to meet mechanical demands, a finding supported by weight-adding experiments and inverted-walking tests that show the decentralized foot control at work. Researchers visualized foot contact with light-refraction imaging, revealing robust, decentralized strategies for navigating varied terrains.