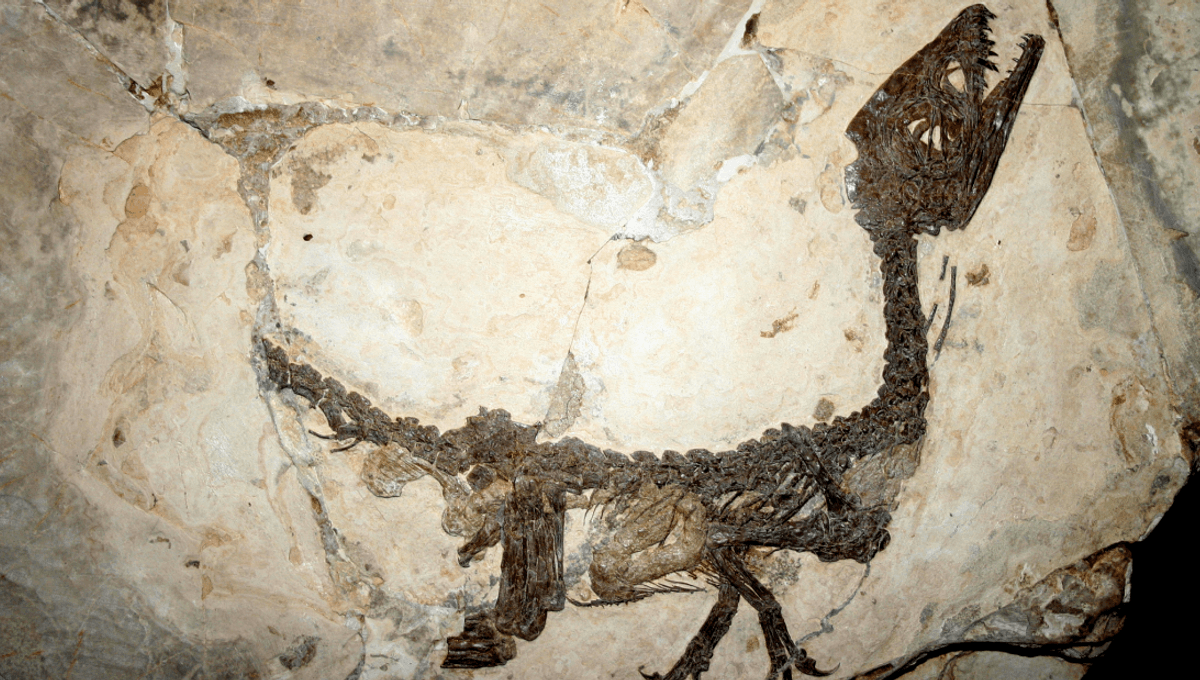

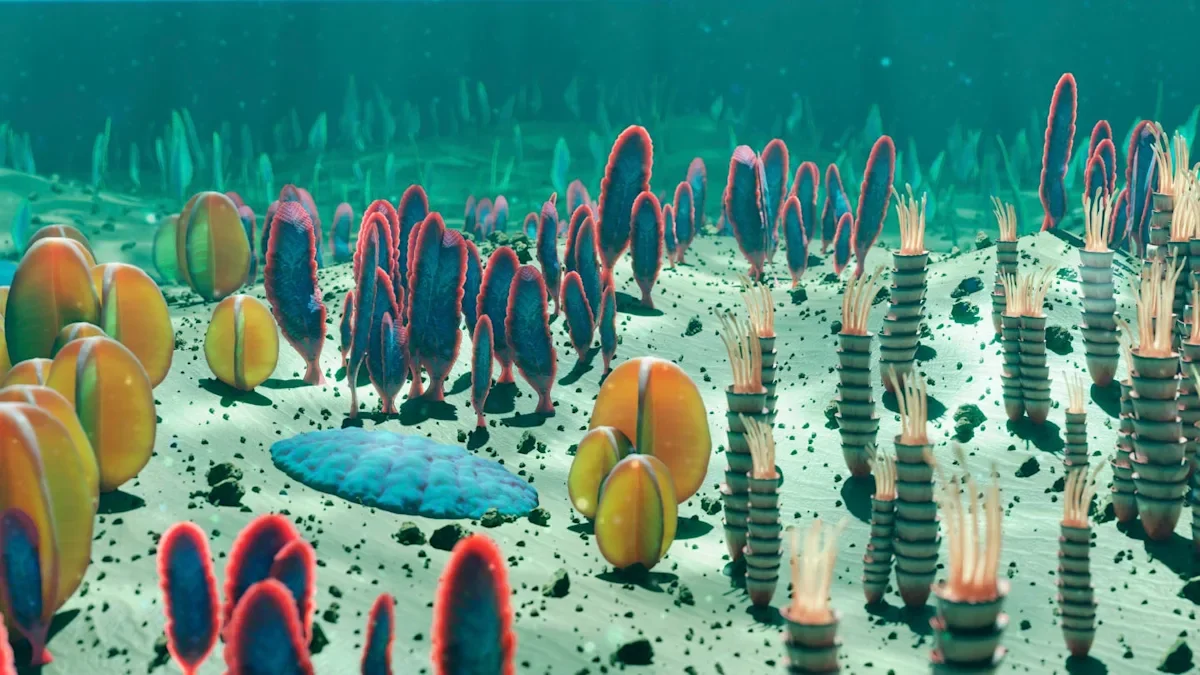

Ancient Sand and Clay Acted as Natural Cement to Preserve Soft-Bodied Fossils

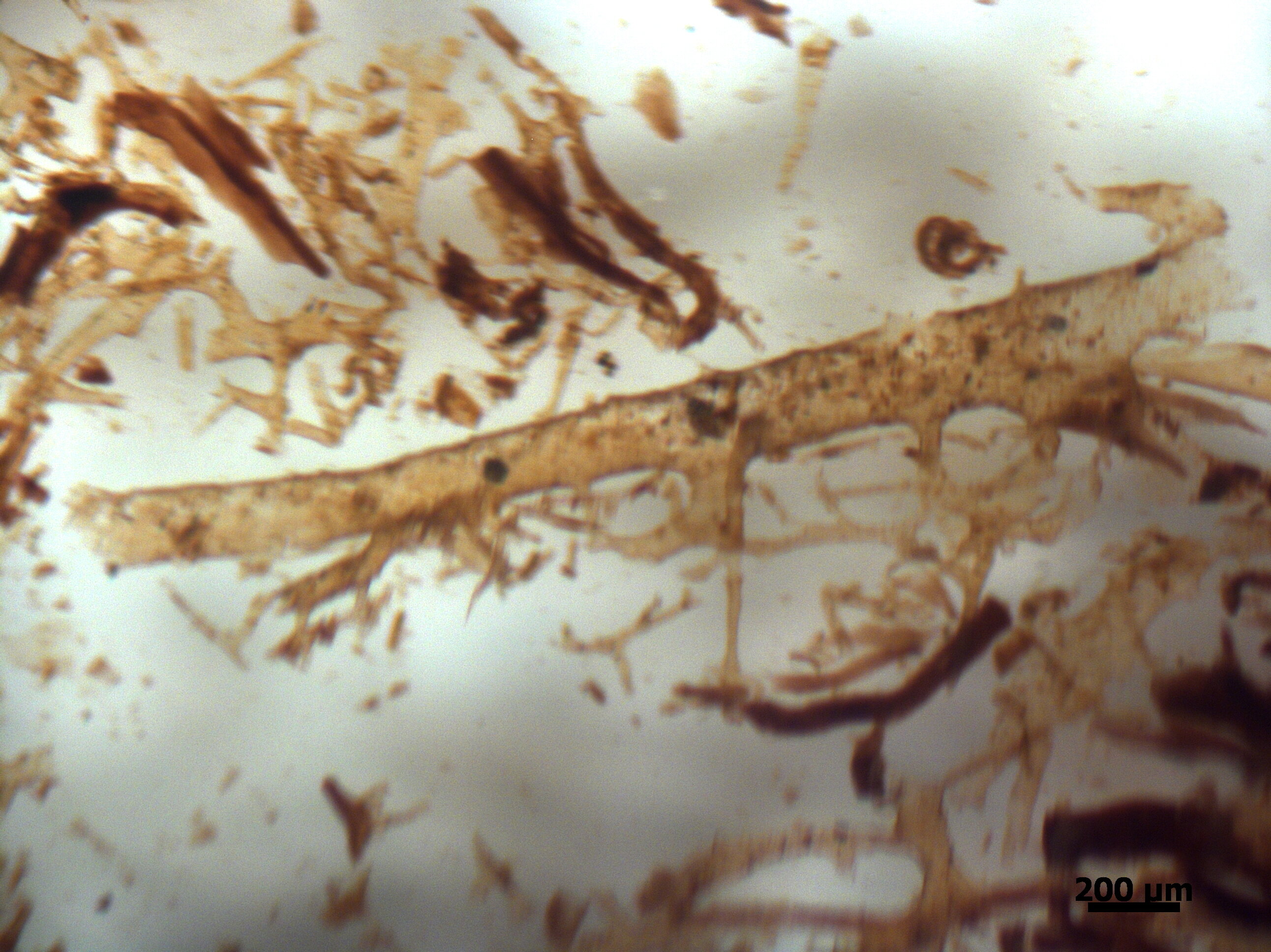

New research suggests the soft-bodied Ediacara Biota fossils were preserved by authigenic clay mineralization on the seafloor, which bound sand grains around buried tissues like a natural cement. Lithium-isotope analyses of Newfoundland sediments show clays forming around the organisms and preserving soft-tissue outlines across continents. This environmental mechanism explains the exceptional fossil record before the Cambrian Explosion, though scientists still debate what these fossils reveal about life prior to that period.