Speeding Clock May Uncover Darwin's Fossil Gaps

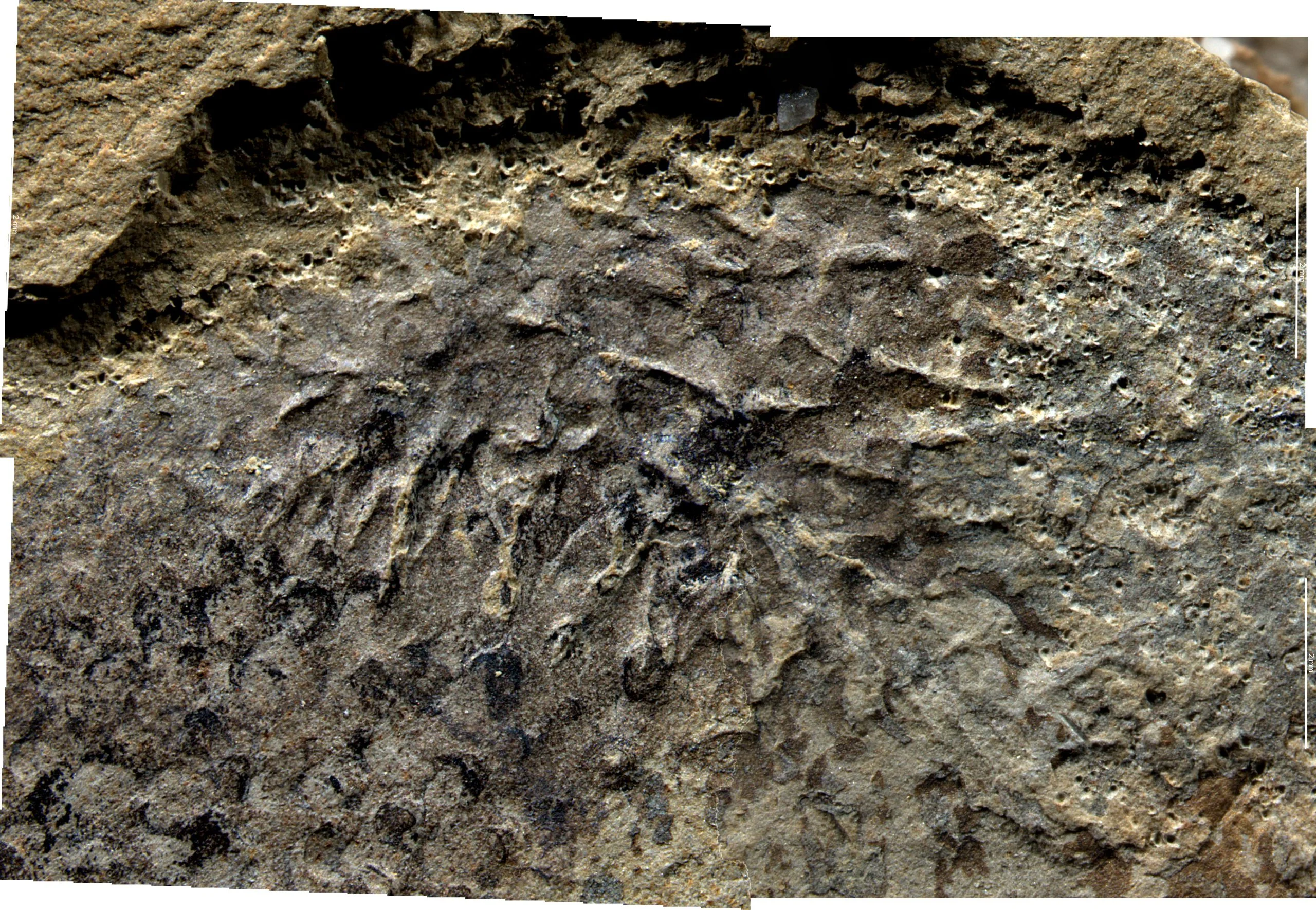

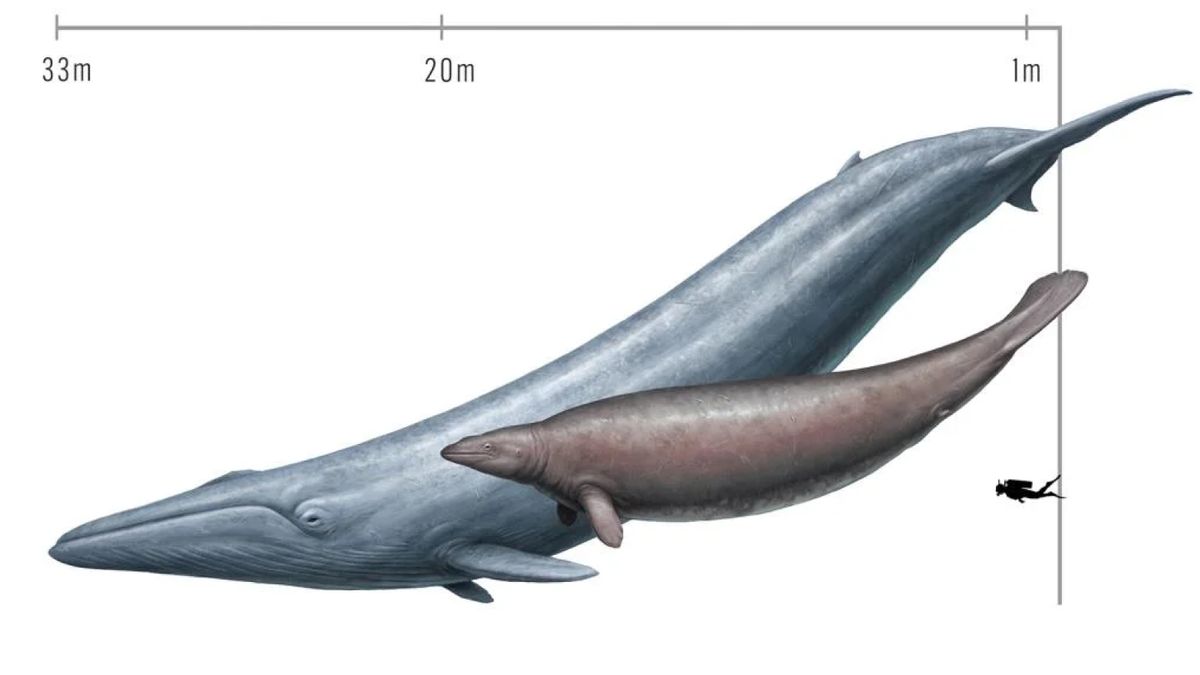

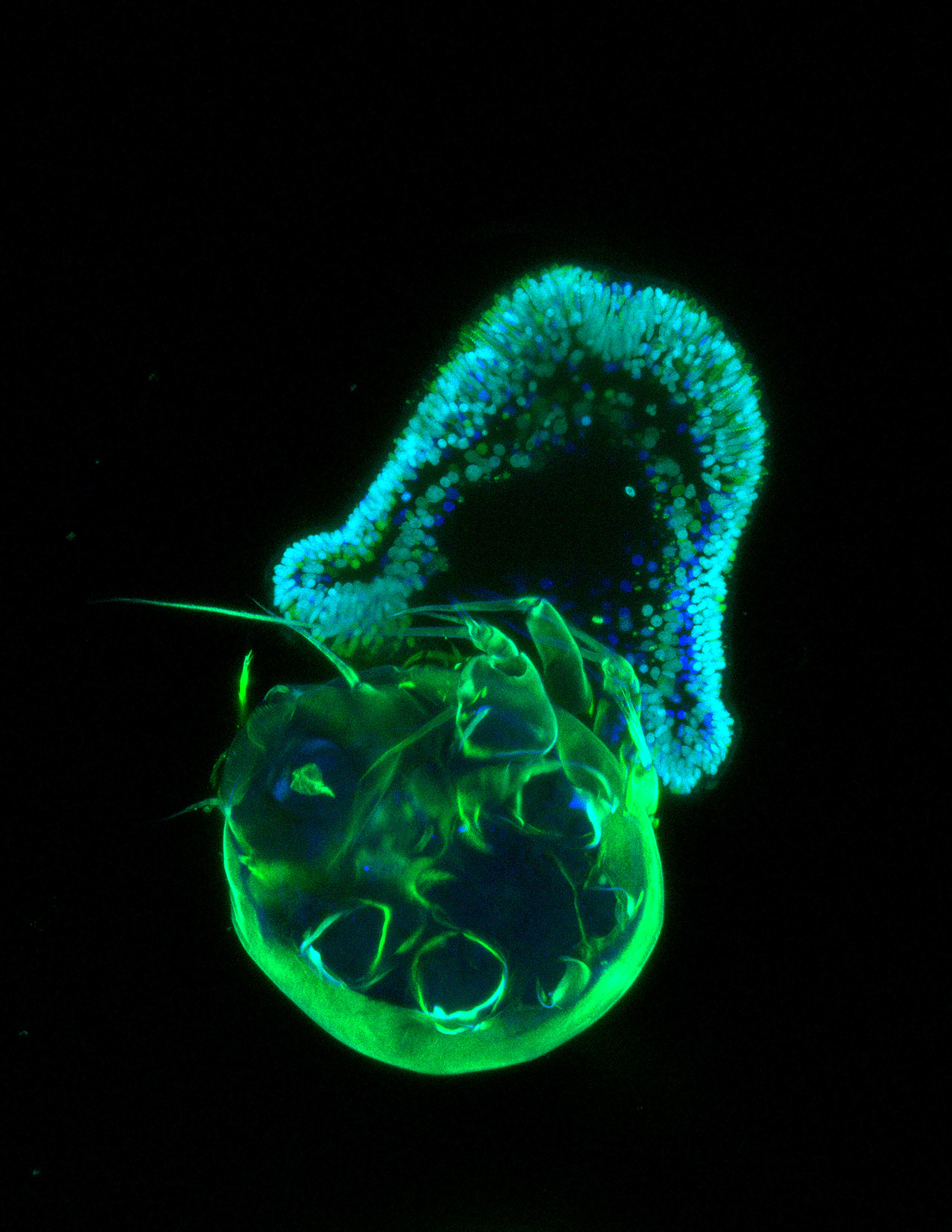

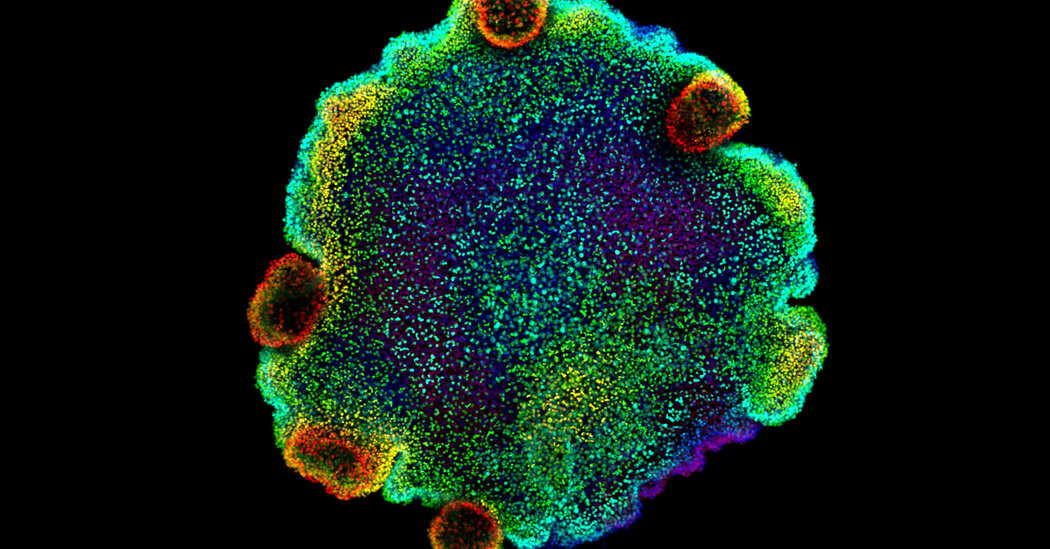

A new theory suggests that the molecular clock, which estimates the timing of evolutionary events, may have sped up during major evolutionary transitions, potentially explaining the 30-million-year gap between the predicted age of the common ancestor of complex animals and their first fossil appearance, thus aligning Darwin's theory with fossil evidence.