Gaia Survey Reveals Diverse Origins for Milky Way Runaway Stars

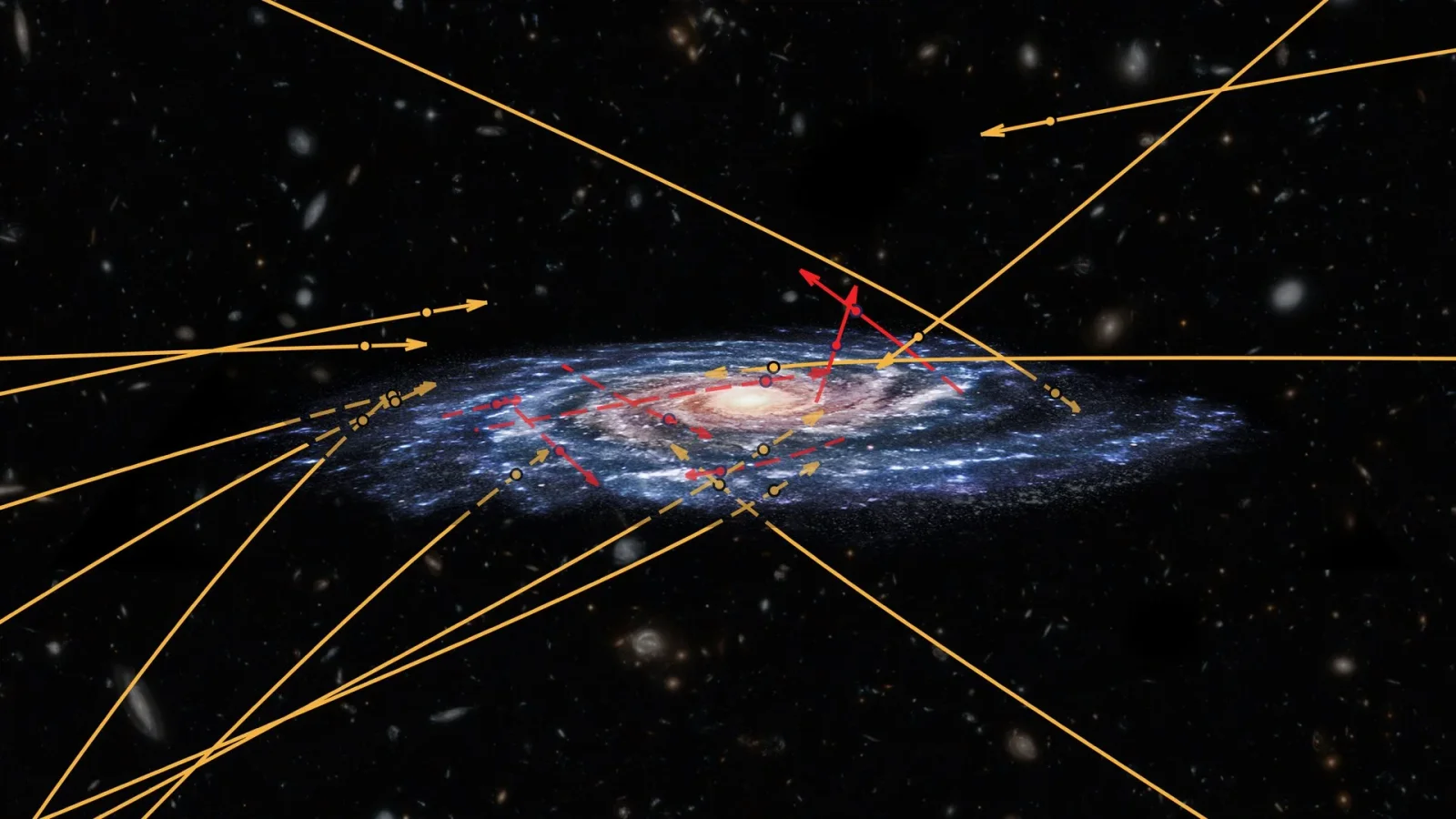

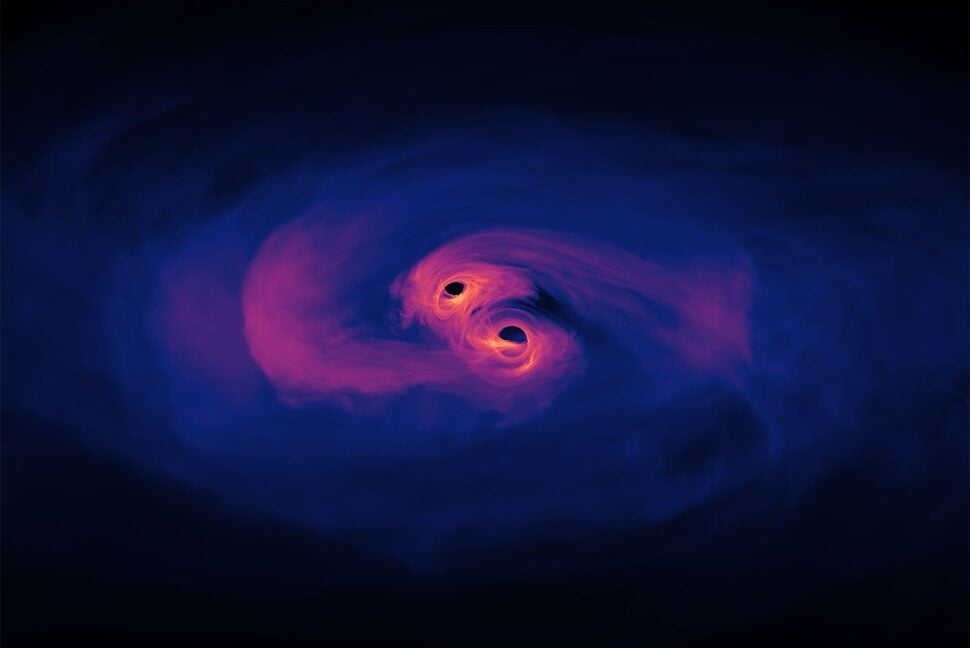

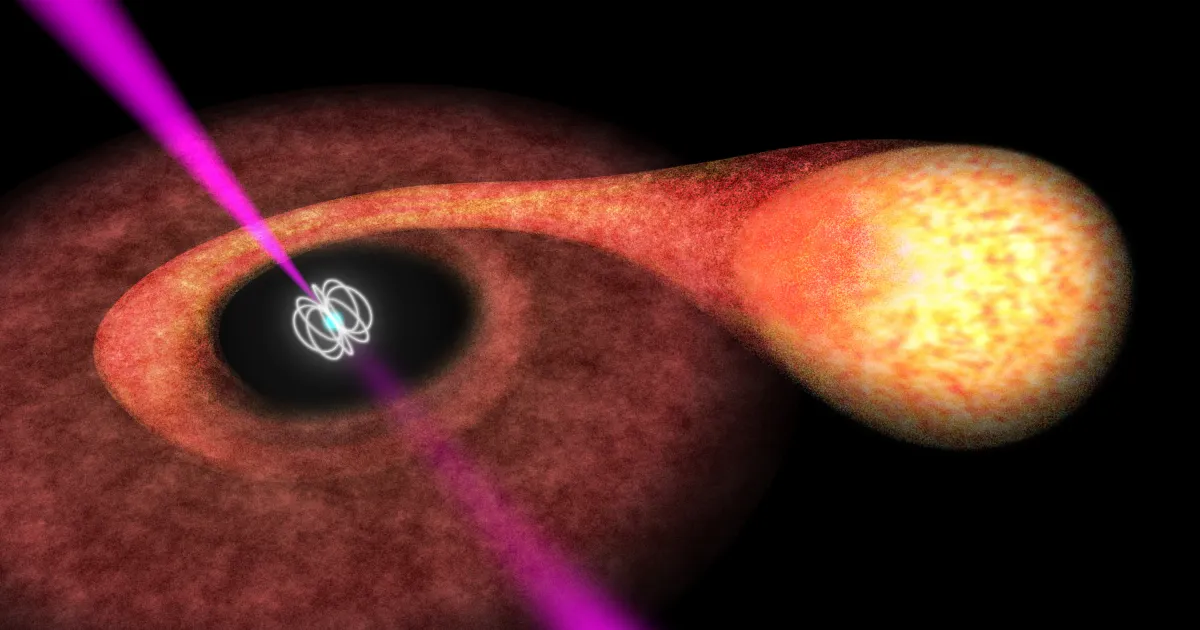

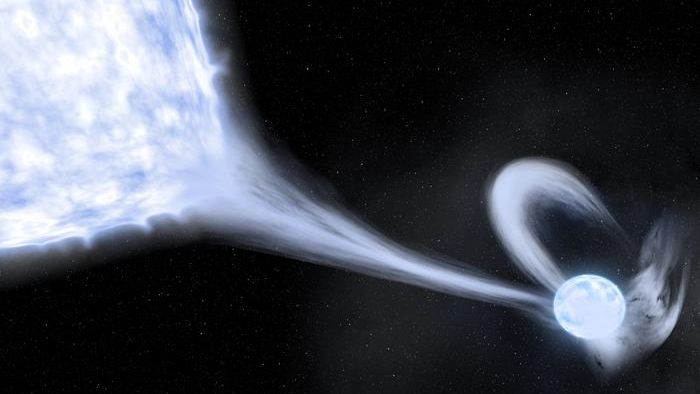

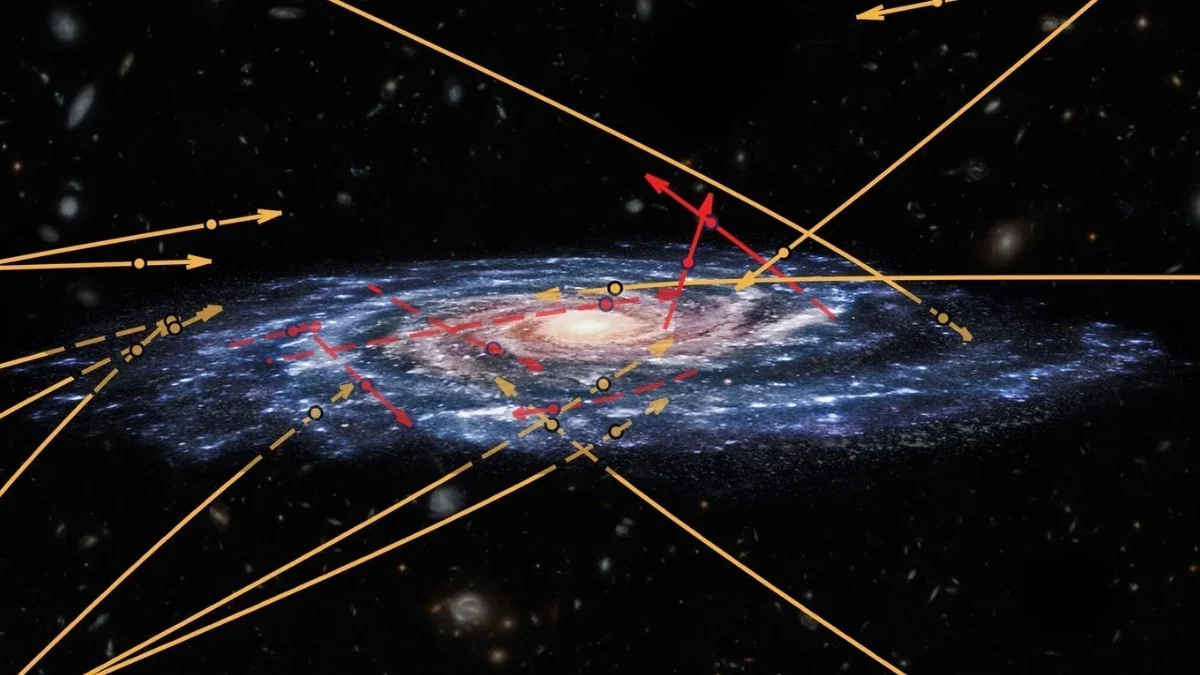

A Gaia- and IACOB-based study of 214 massive O-type runaway stars finds that most did not originate as binary companions; slower rotators are common, faster rotators often link to binary-supernova ejections, and the fastest stars tend to be single, likely ejected by gravitational interactions in young clusters. The researchers identify 12 runaway binaries, including candidates with neutron stars or black holes, showing multiple ejection mechanisms that shape galactic evolution.