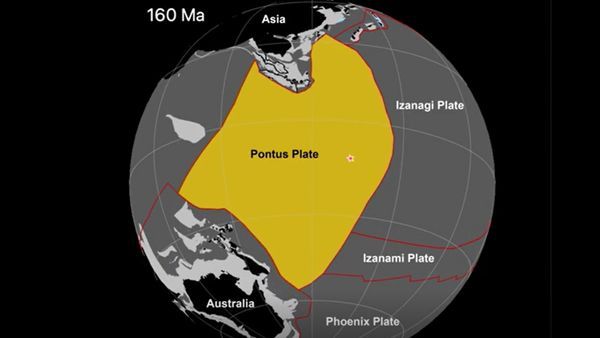

Five-Block Boundary at Mendocino Triple Junction Rewrites Quake Forecasts

A new analysis of tiny, low-frequency earthquakes around the Mendocino triple junction shows the boundary is made up of five moving blocks rather than three plates, with shallower subduction than previously thought, prompting updates to earthquake hazard models and potentially improving predictions for major quakes along California and Cascadia.