Scientists Uncover the Hot Secret Stabilizing Earth's Continents and Life

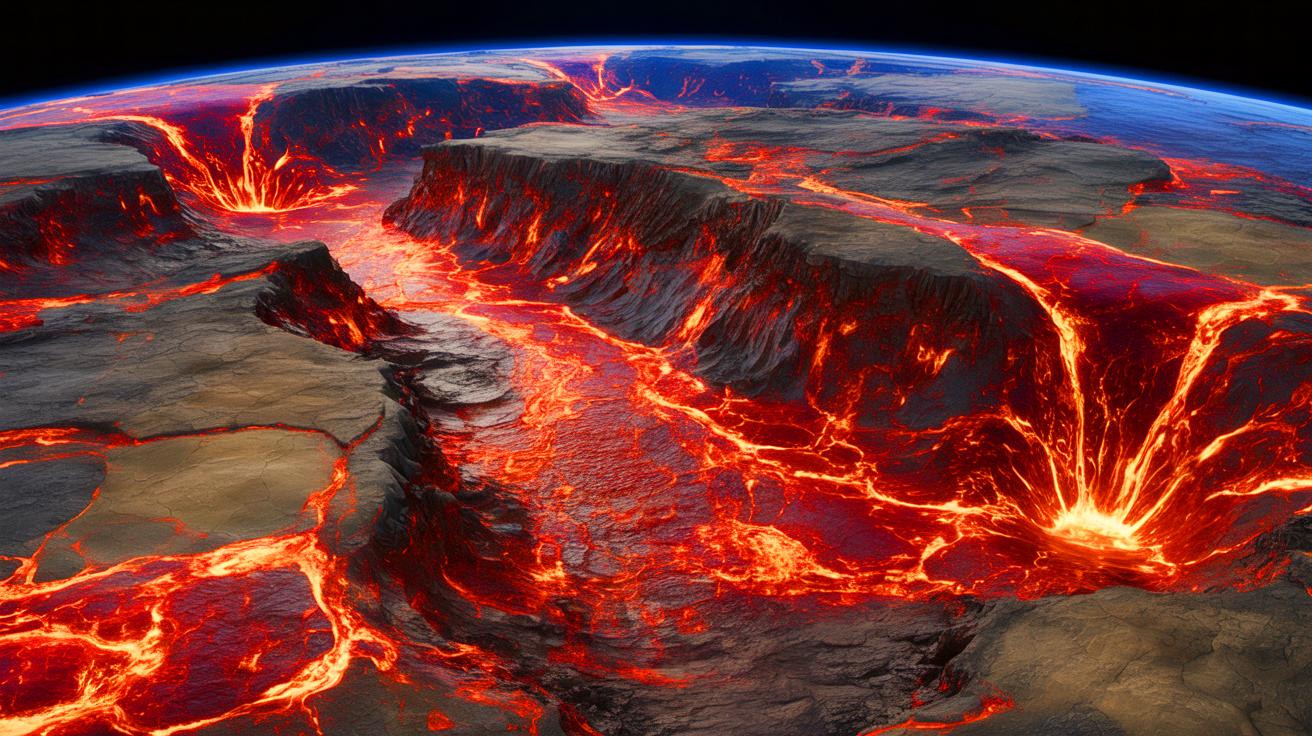

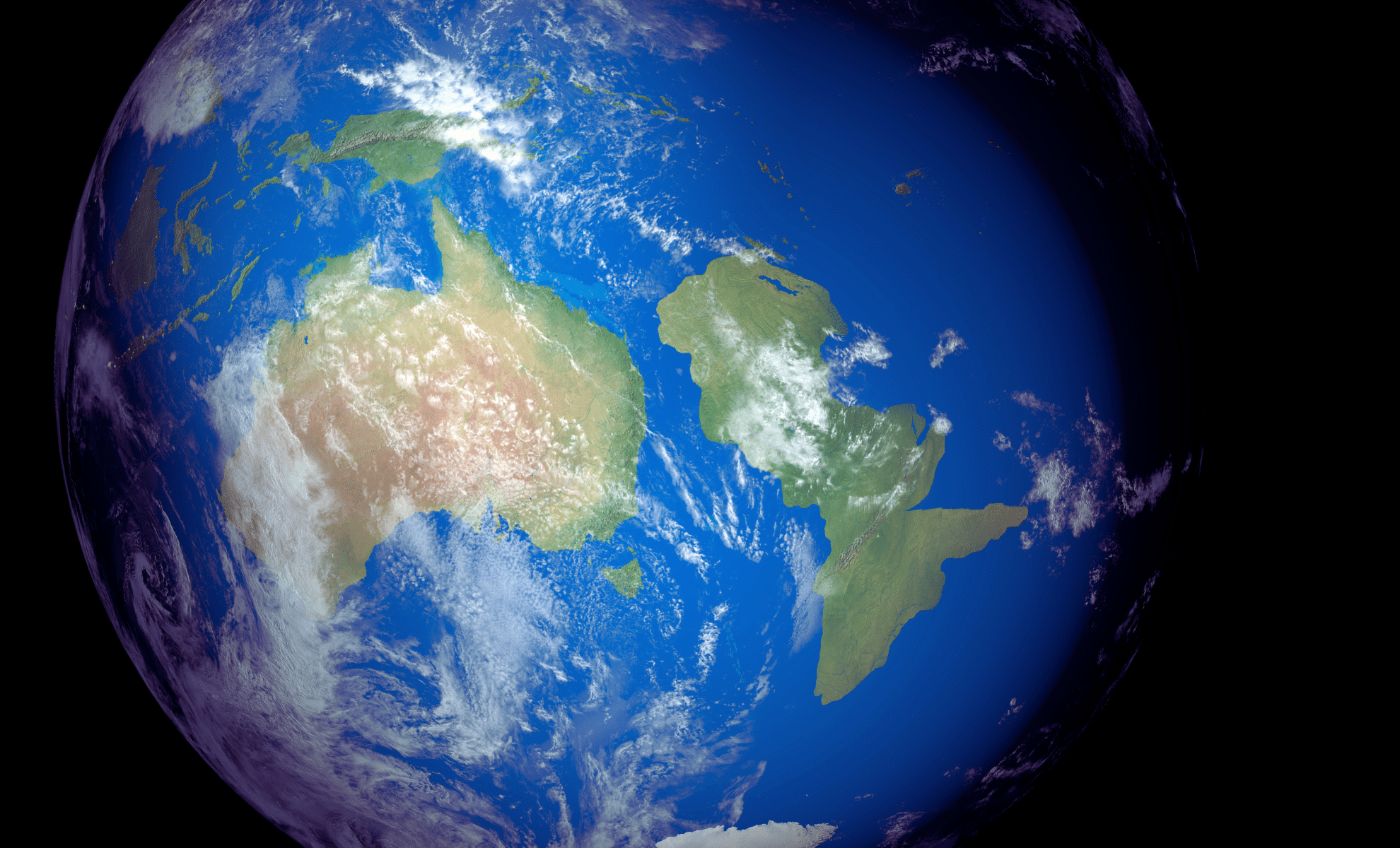

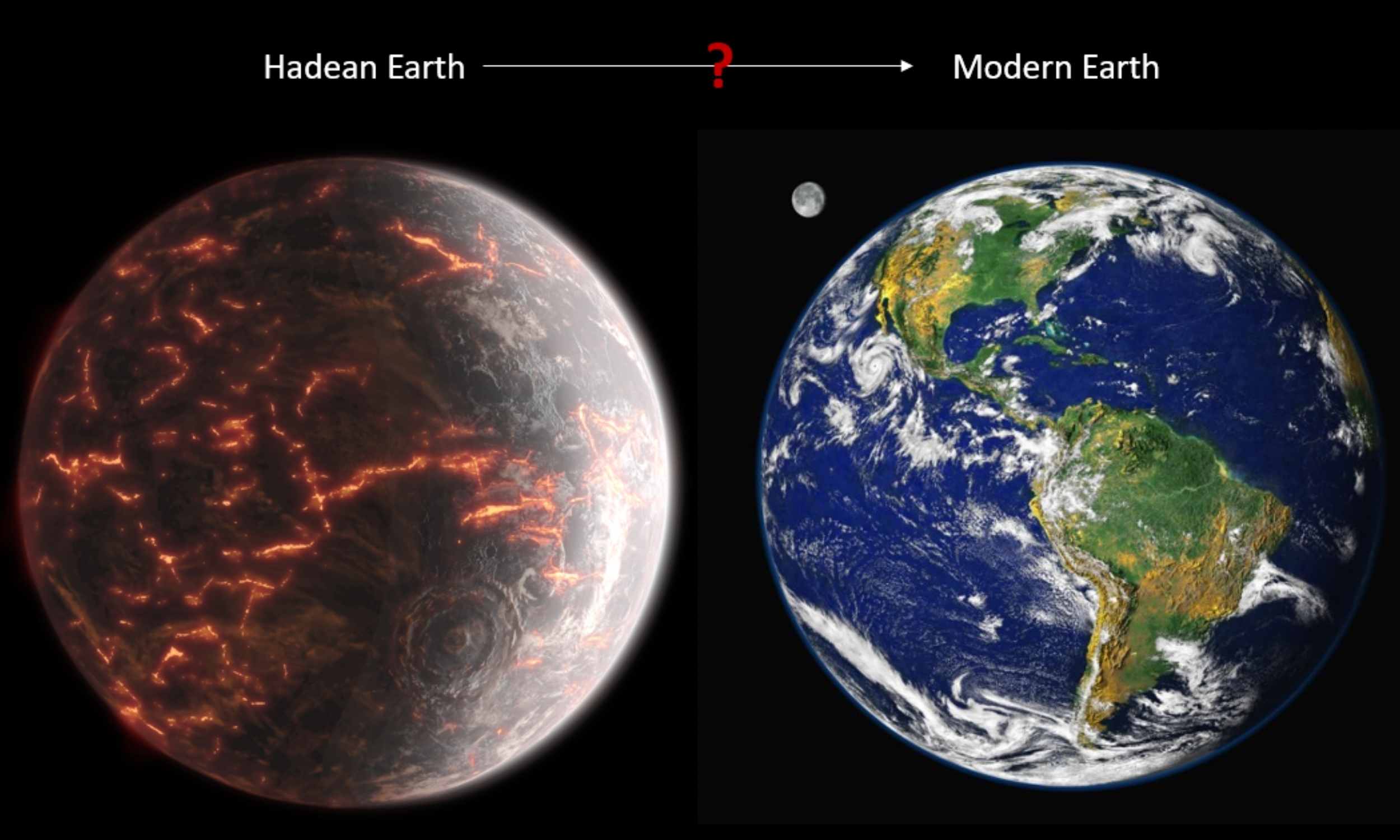

New research reveals that Earth's stable continents were formed by extremely high temperatures deep within the crust, driven by radioactive decay of elements like uranium and thorium, which facilitated the cooling and solidification of the crust. These processes, akin to forging metal, shaped Earth's landmasses and created a stable foundation for life, offering insights into planetary habitability and guiding the search for life on other planets.