New Imaging Technique Unveils Brain Differences in Autism and Schizophrenia

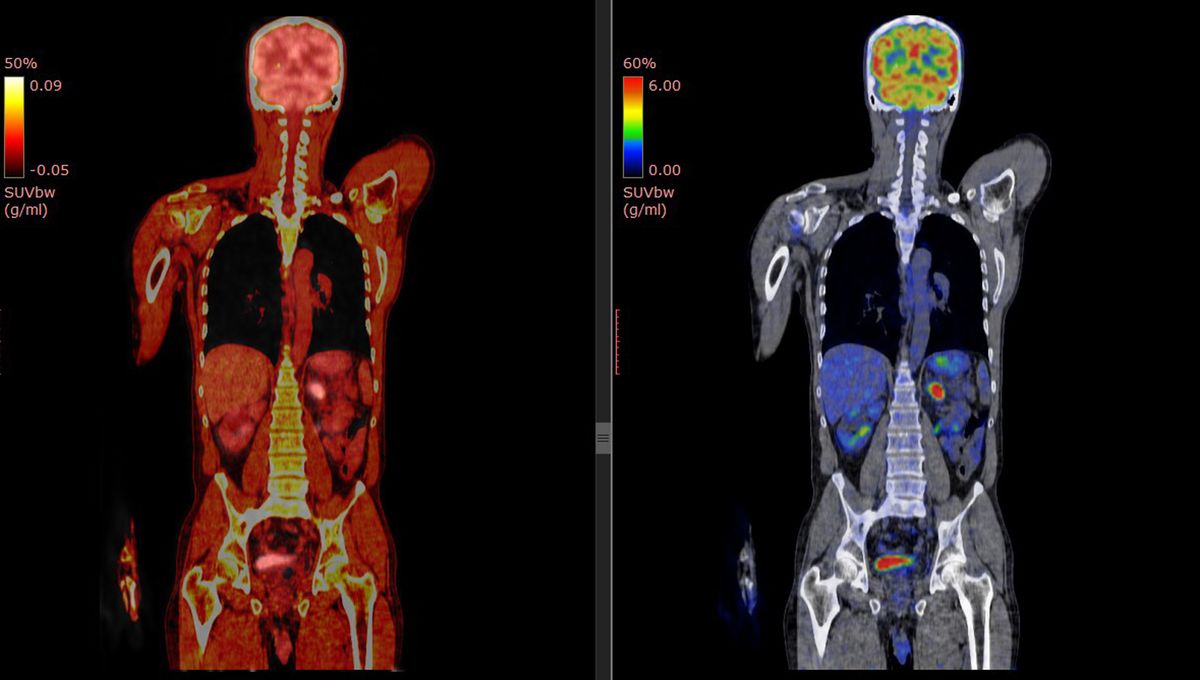

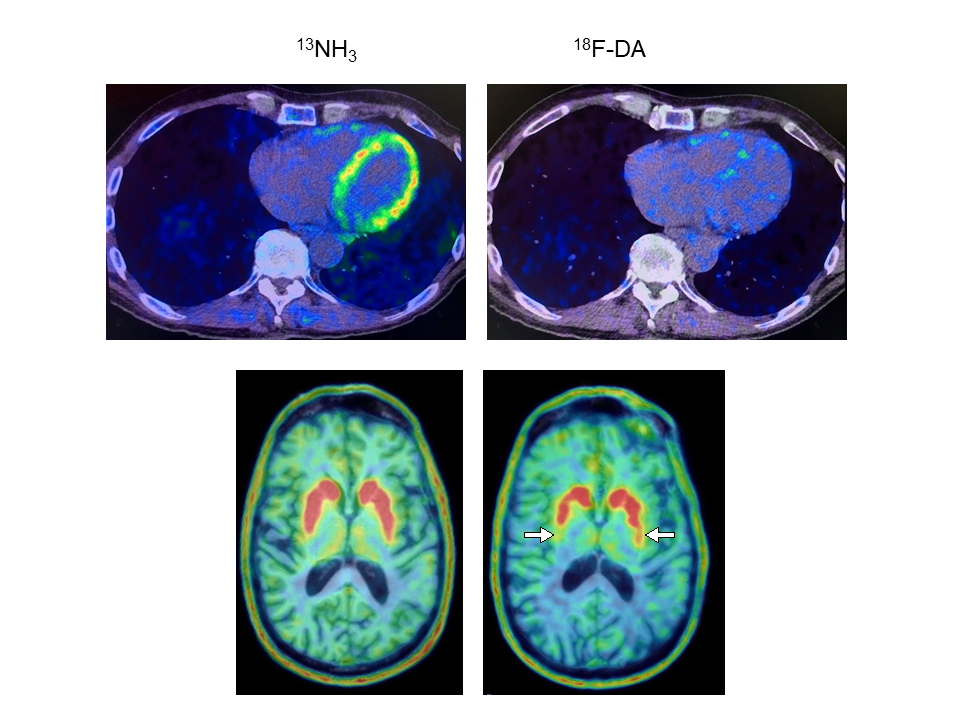

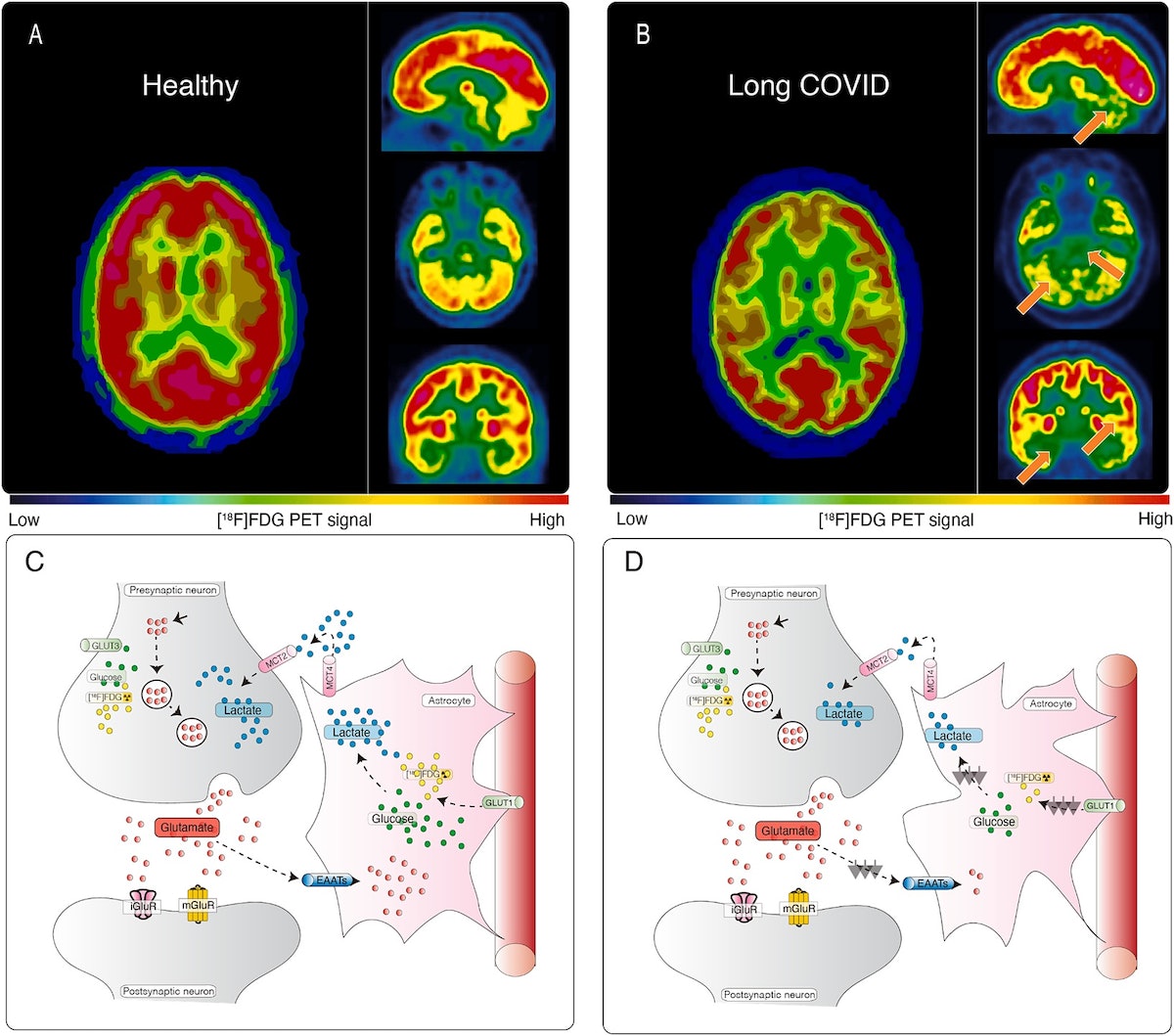

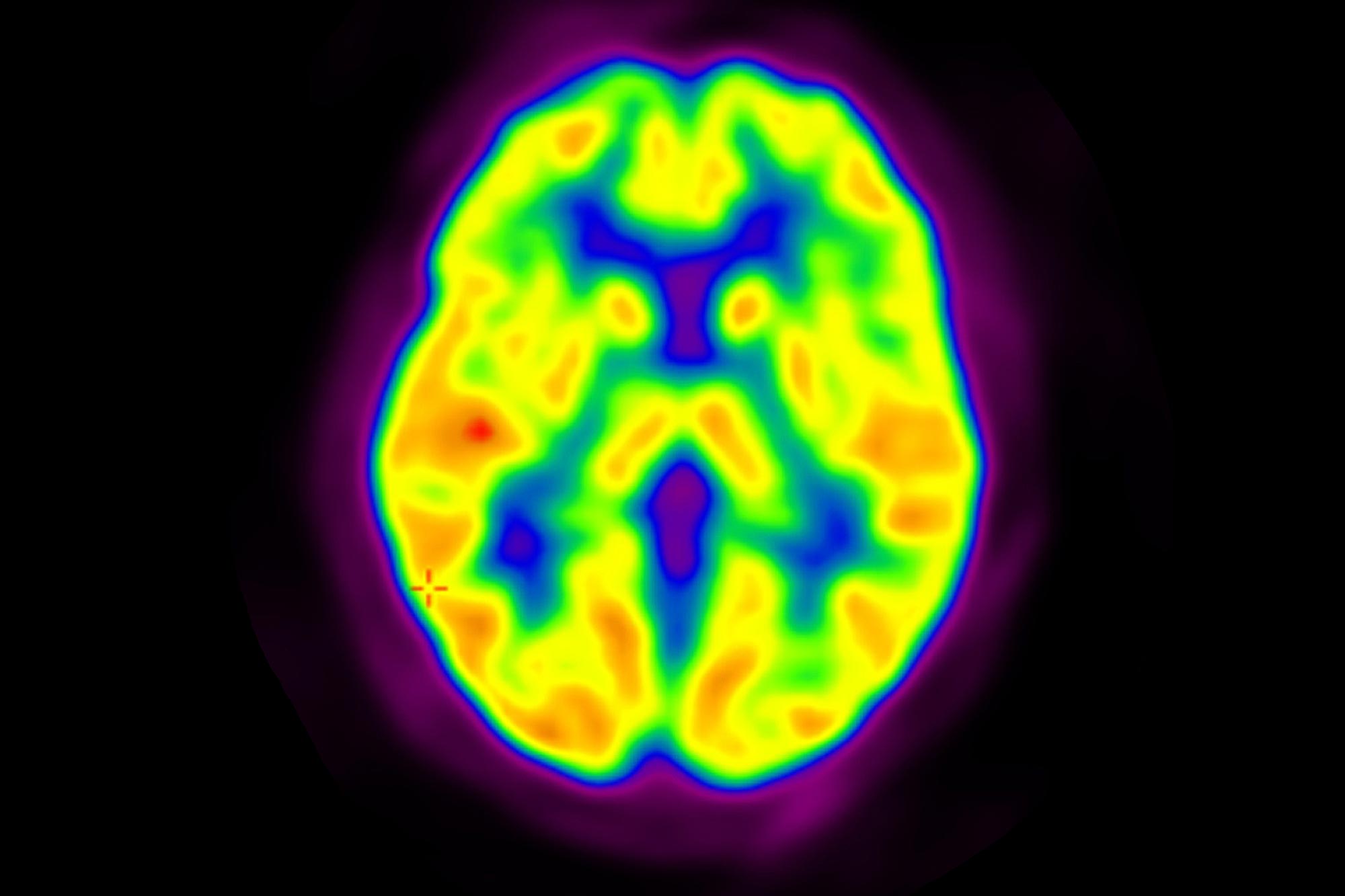

A new study using PET scans has found that autistic individuals have fewer synapses in their brains, which correlates with more pronounced autism traits such as social and communication difficulties. This discovery marks the first time synaptic density has been measured in living autistic individuals and could revolutionize diagnostic and treatment approaches, potentially leading to more targeted interventions. The research highlights the importance of understanding the biological underpinnings of autism to improve support and quality of life for those on the spectrum.