Gender Differences in the Biological Roots of PTSD

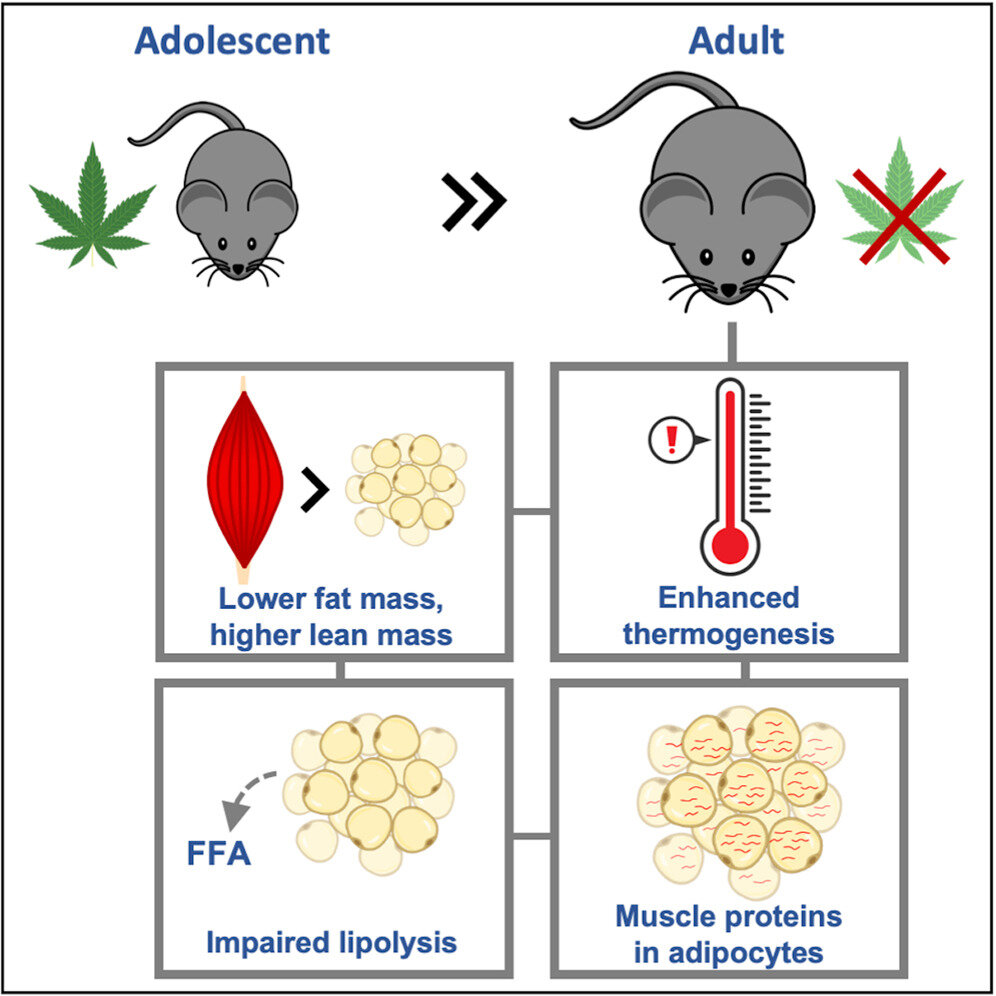

A study reveals that PTSD has different biological roots in men and women, with men showing deficits in stress-regulating lipids and women exhibiting heightened systemic inflammation, suggesting the need for sex-specific treatments.