Embryo Cell Division Driven by Mechanical Ratchet, Not a Full Contractile Ring

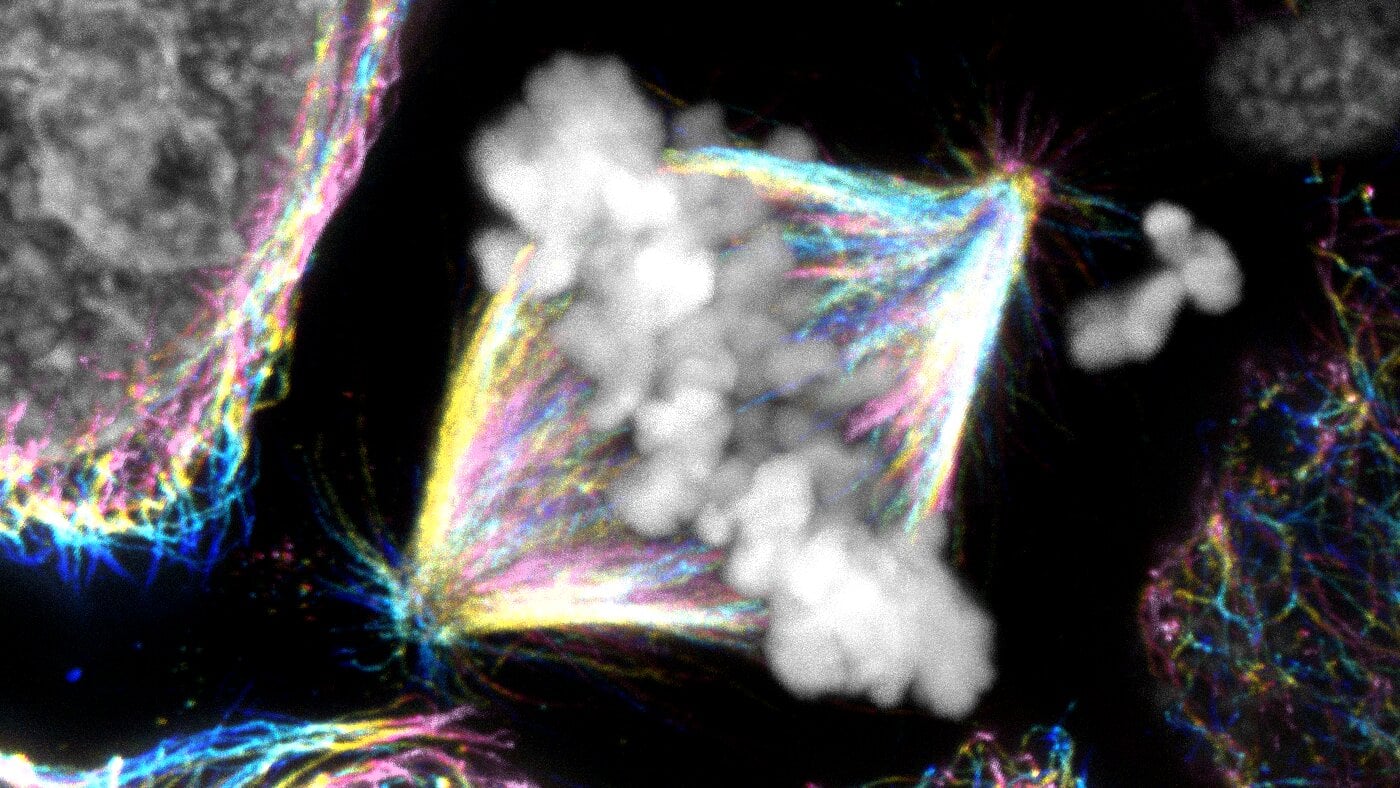

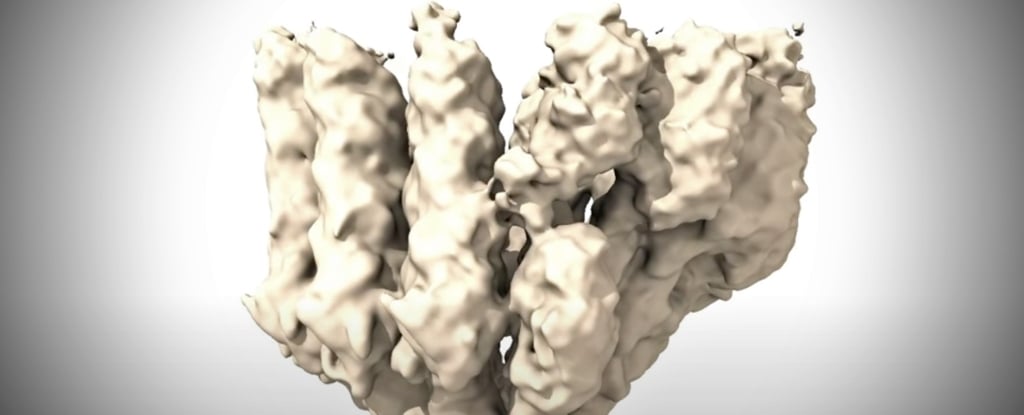

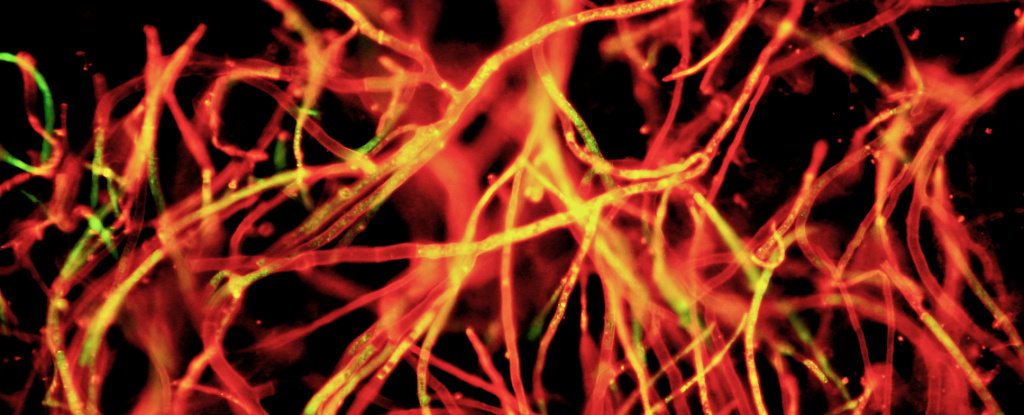

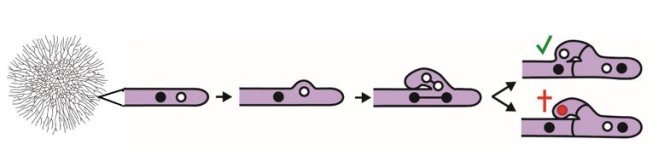

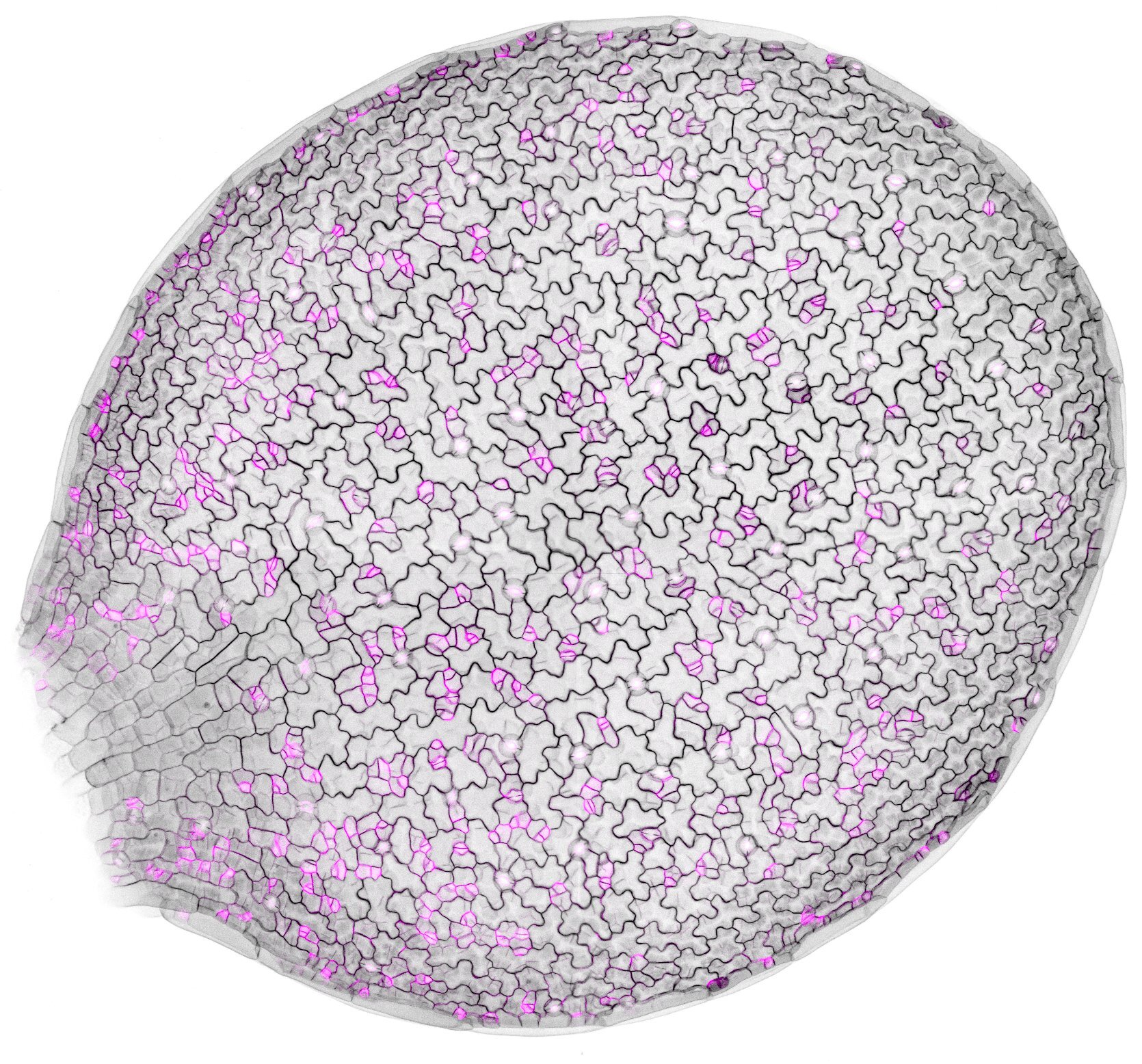

Researchers from the Brugués group at TU Dresden report in Nature a new mechanism for early embryonic cell division in yolk-rich cells: a mechanical ratchet that drives division without a fully closed actin contractile ring. By showing microtubule asters stiffen the cytoplasm during interphase and the cytoplasm becomes more fluid in M-phase, they find the actin band can ingress across multiple cell cycles, anchored by microtubules and re-stabilized when the cytoplasm stiffens again. This challenges textbook models and may apply broadly to yolk-rich embryos across species.