Flores Hobbits' Small Size Resulted from Slowed Childhood Growth, Study Finds

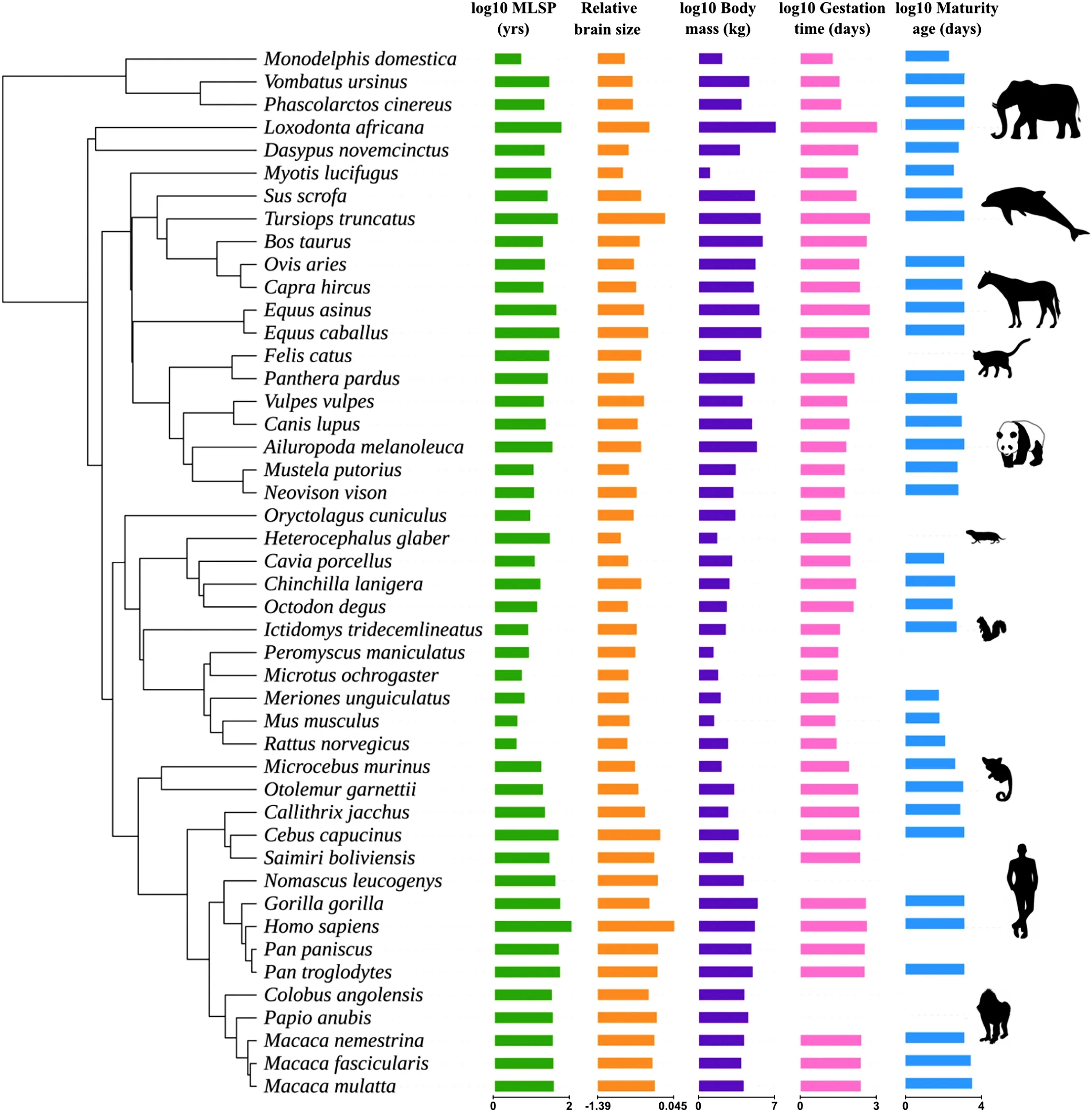

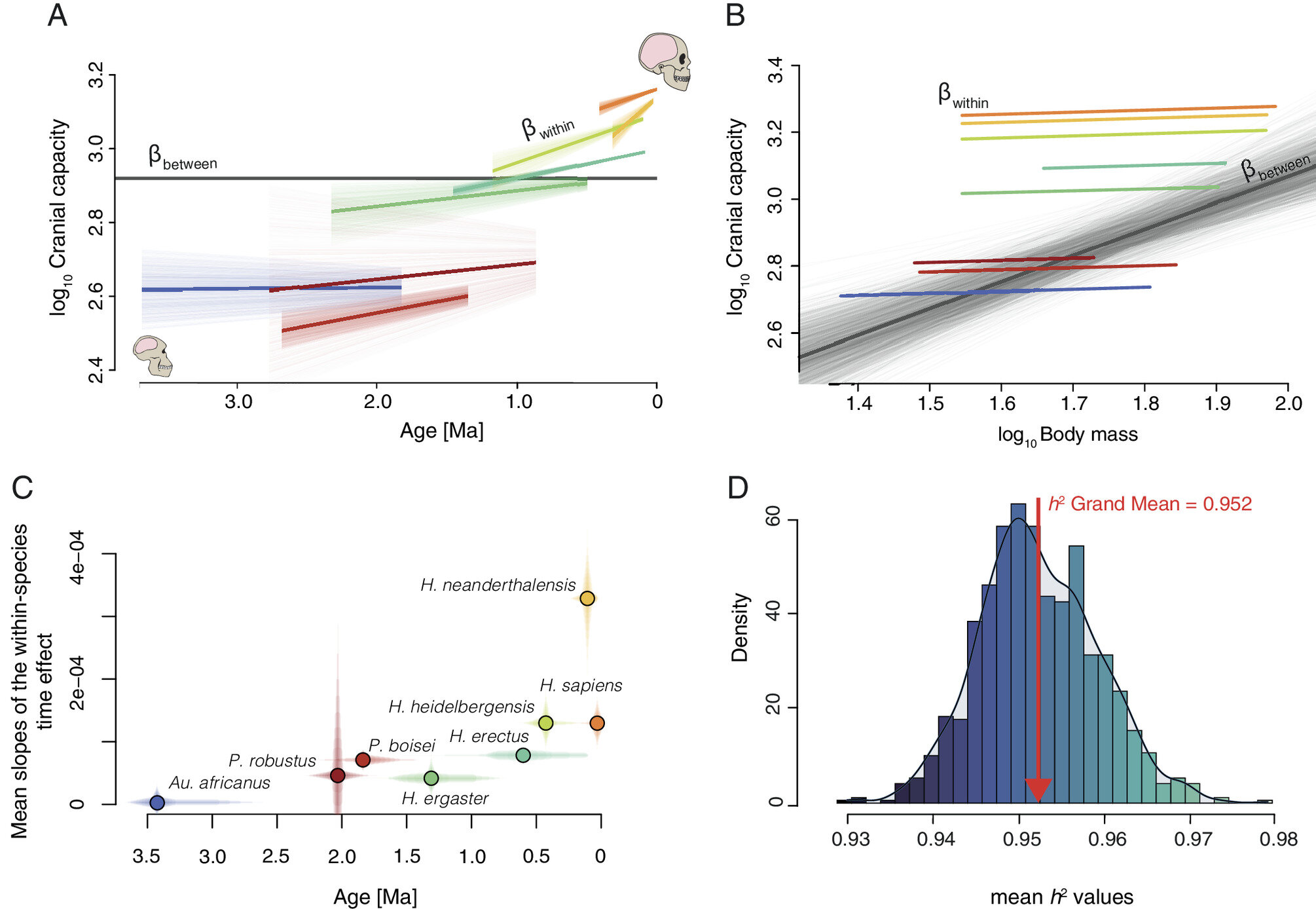

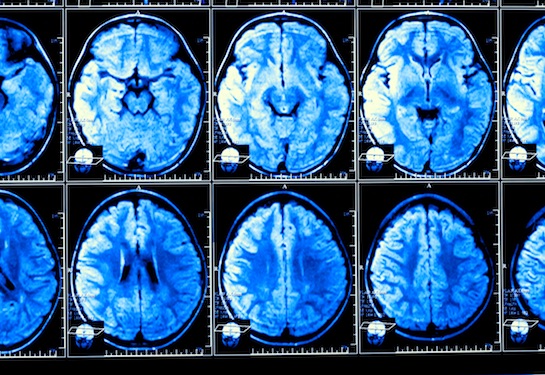

New research suggests that the small size of Homo floresiensis, or Hobbits, resulted from slowed growth during childhood rather than in utero development, challenging previous assumptions that brain size increase was the primary driver of human evolution. The study highlights how tooth and brain size relationships can provide insights into fossil species, and emphasizes that small body size on islands is an adaptive response, not a reflection of lower intelligence.