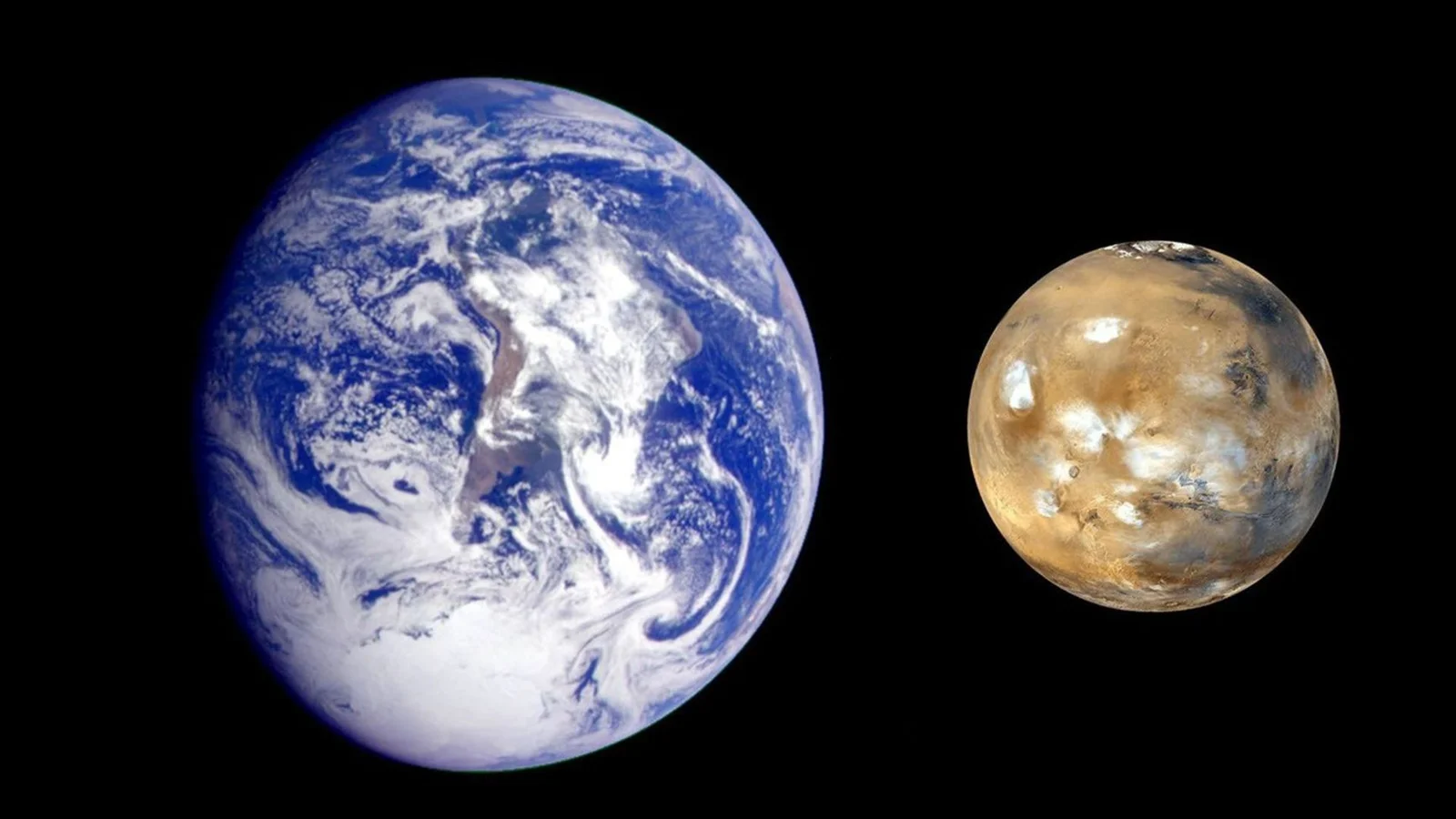

Mars helps stabilize Earth's climate by taming its tilt, new simulations suggest

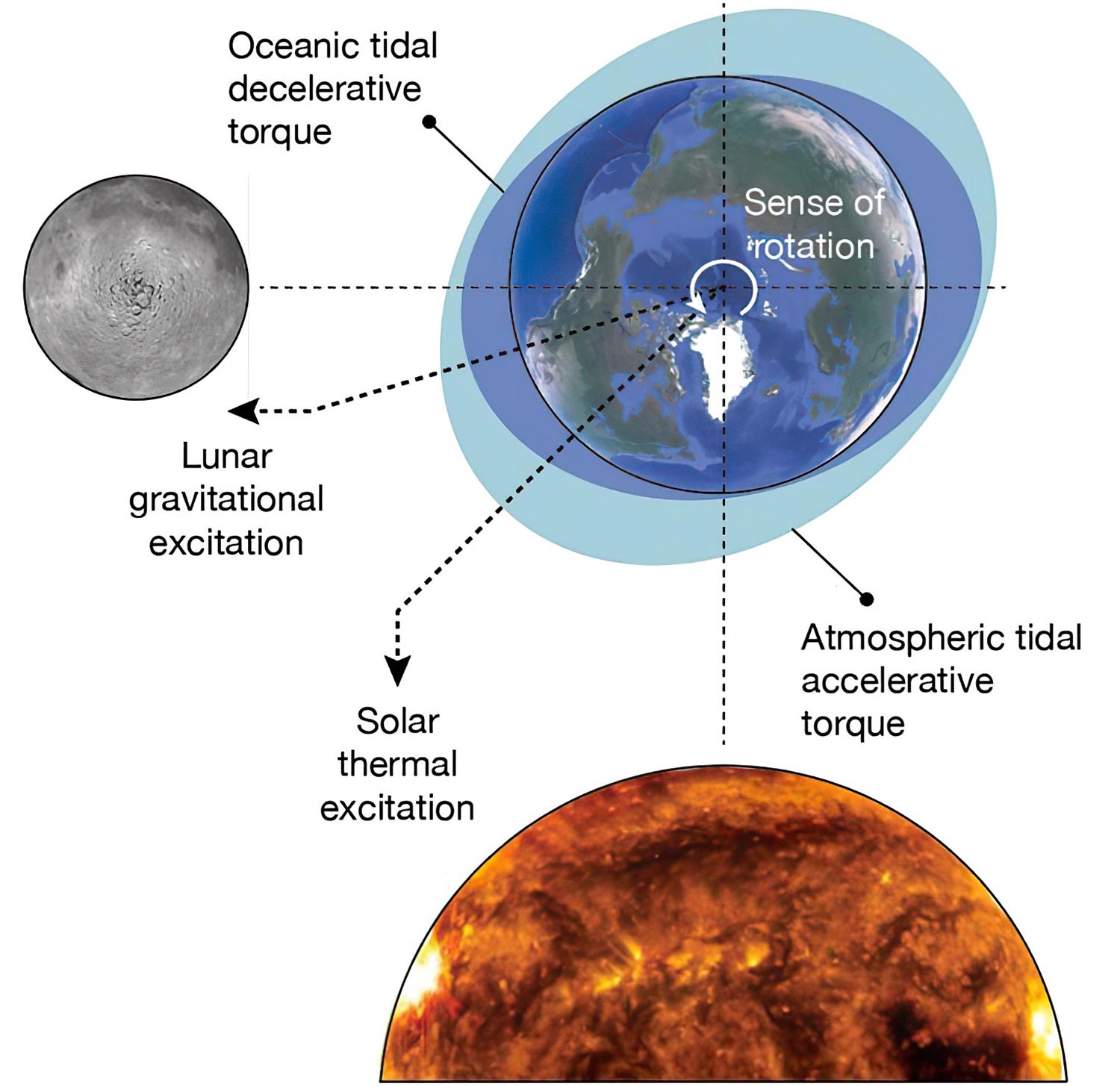

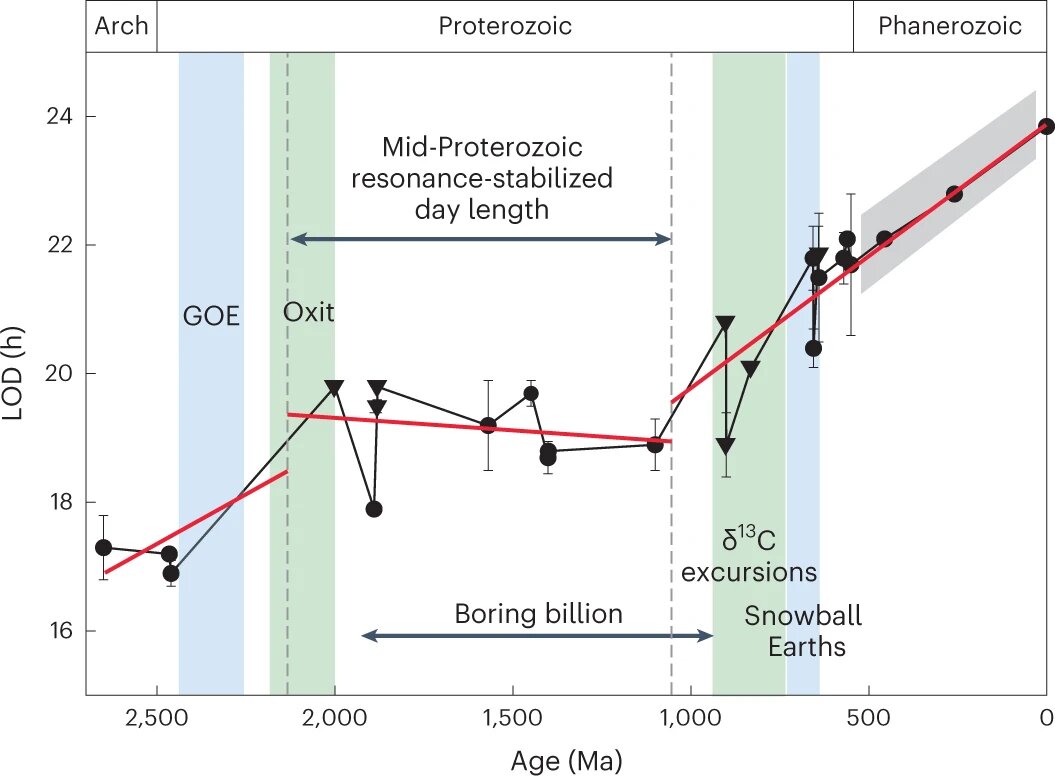

New simulations quantify Mars' gravitational influence on Earth, showing Mars helps stabilize Earth's axial tilt and orbital eccentricity over Milankovitch cycles, potentially shaping climate over hundreds of thousands to millions of years; removing Mars from the system causes major cycles to vanish, while increasing Mars' mass dampens tilt changes, suggesting Mars plays a stabilizing role in Earth's climate and could influence how we think about habitable worlds elsewhere.