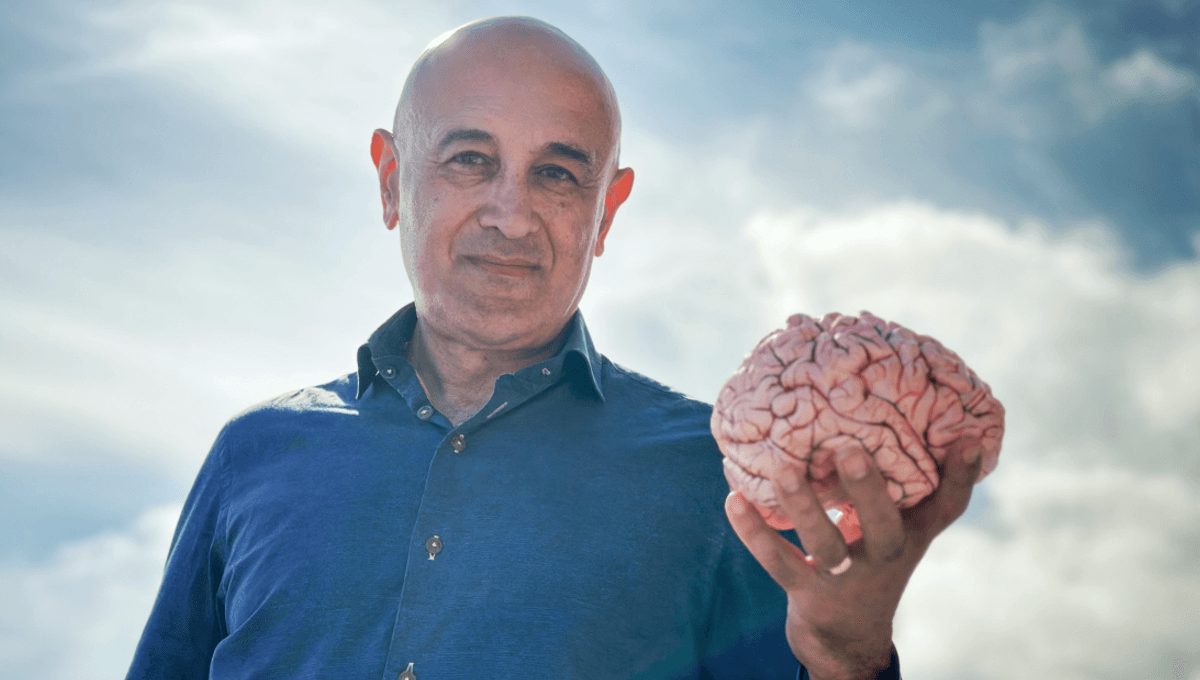

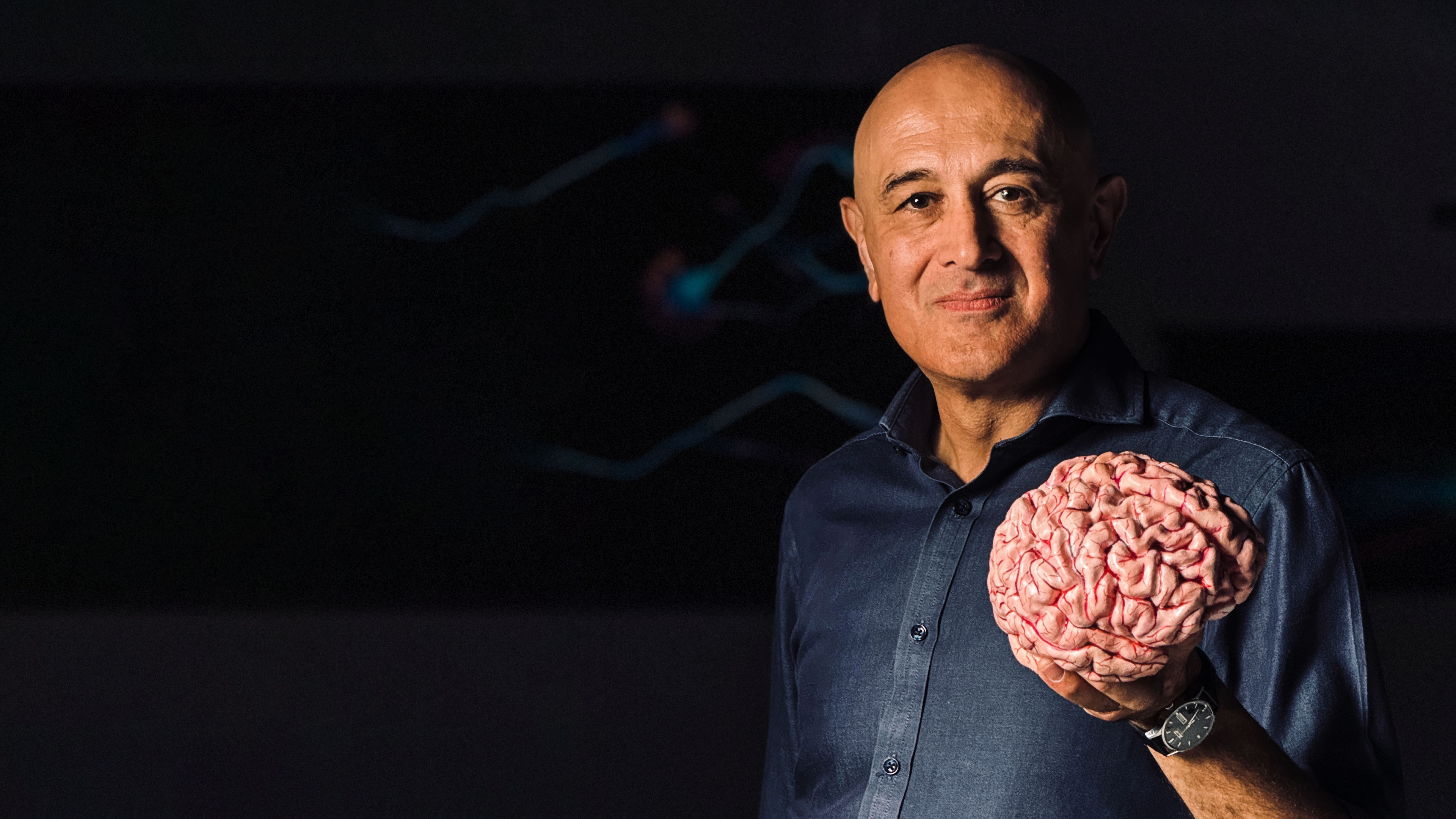

Finger Clues Hint at Prenatal Hormones Behind Brain Growth

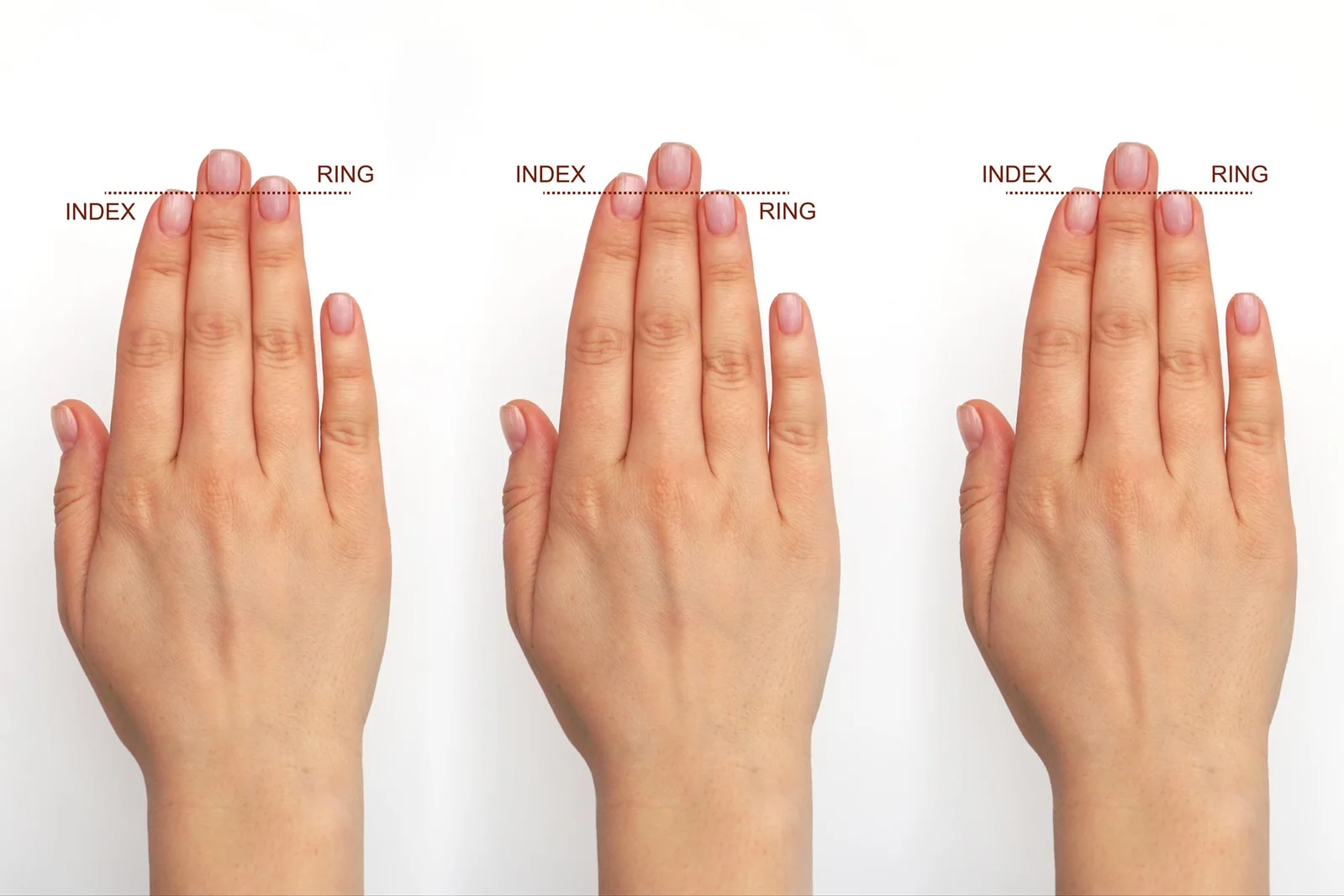

Newborns showed a link between higher prenatal estrogen exposure (indicated by a higher 2D:4D finger ratio) and larger head size in boys, suggesting hormones before birth may have helped drive brain growth during human evolution. Girls did not show the same pattern, and the findings contribute to the idea that brain expansion carried tradeoffs for male health, consistent with the estrogenized ape hypothesis.