Company Launches Revolutionary Quantum Processor with 100x Density Boost

A company has announced a new quantum processor that is 100 times denser than any existing technology, marking a significant advancement in quantum computing capabilities.

All articles tagged with #density

A company has announced a new quantum processor that is 100 times denser than any existing technology, marking a significant advancement in quantum computing capabilities.

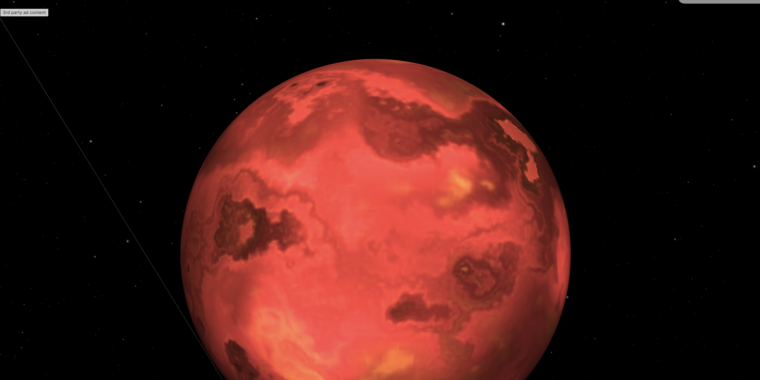

A new study suggests that certain asteroids in our solar system may be composed of naturally occurring "superheavy elements" that are beyond those listed in the periodic table. These asteroids, known as compact ultra dense objects (CUDOs), are denser than any element found on Earth. Previous research proposed that the density of CUDOs could be explained by the presence of dark matter particles, but the new study mathematically demonstrates that unknown classes of chemical elements beyond the periodic table could account for their density. These superheavy elements, if they exist, could shed light on how they were formed and why they have not been discovered outside of asteroids. The study also supports the theoretical existence of a region of stable superheavy elements around atomic number 164, known as the "island of stability."

Some asteroids in our solar system may be composed of naturally occurring "superheavy elements" that are denser than any element on Earth, according to a new study. These asteroids, known as compact ultra dense objects (CUDOs), have densities that cannot be explained by known elements in the periodic table. Previous research suggested that dark matter particles could account for their density, but the new study proposes the existence of unknown classes of chemical elements beyond the periodic table. These superheavy elements, if they exist, could explain the density of CUDOs like the asteroid 33 Polyhymnia. The study also supports the theoretical concept of an "island of stability" for superheavy elements, where they could be stable and exist for short periods of time.

Asteroid 33 Polyhymnia in the solar system's asteroid belt is believed to be so dense that it may contain elements never before seen on Earth, potentially reaching a threshold of 164 protons per atomic nucleus. The density of this hypothetical element matches the density already measured for the asteroid, suggesting it could be a compact ultradense object (CUDO) containing undiscovered elements. If confirmed, this discovery would challenge the current understanding of the Periodic Table and open up new possibilities for scientific exploration within our solar system.

Exoplanet GJ 367b, dubbed the "super Mercury," is an extreme planet that is almost twice as dense as Earth, suggesting it is made of solid iron. Scientists believe that GJ 367b was once the core of an ancient rocky planet, with the iron core now making up over 90% of the planet. Possible formation scenarios include collisions that stripped away its outer layers or intense radiation from orbiting close to its star. Further investigations into GJ 367b could provide insights into the formation and evolution of rocky planets and those with short orbital periods.

Scientists speculate that there may be naturally occurring, stable elements beyond the periodic table, even beyond the unstable superheavy elements. Theoretical work suggests an island of stability around atomic number 164, where these elements could exist. Researchers from the University of Arizona used the Thomas-Fermi model to explore the atomic structure of hypothetical superheavy elements and found that their density range aligns with the high density measurement of the asteroid 33 Polyhymnia. This suggests that extreme mass density in compact ultradense objects like asteroids could be explained without invoking strange or dark matter. The study demonstrates the utility of the Thomas-Fermi model for investigating the properties of hypothetical superheavy elements.

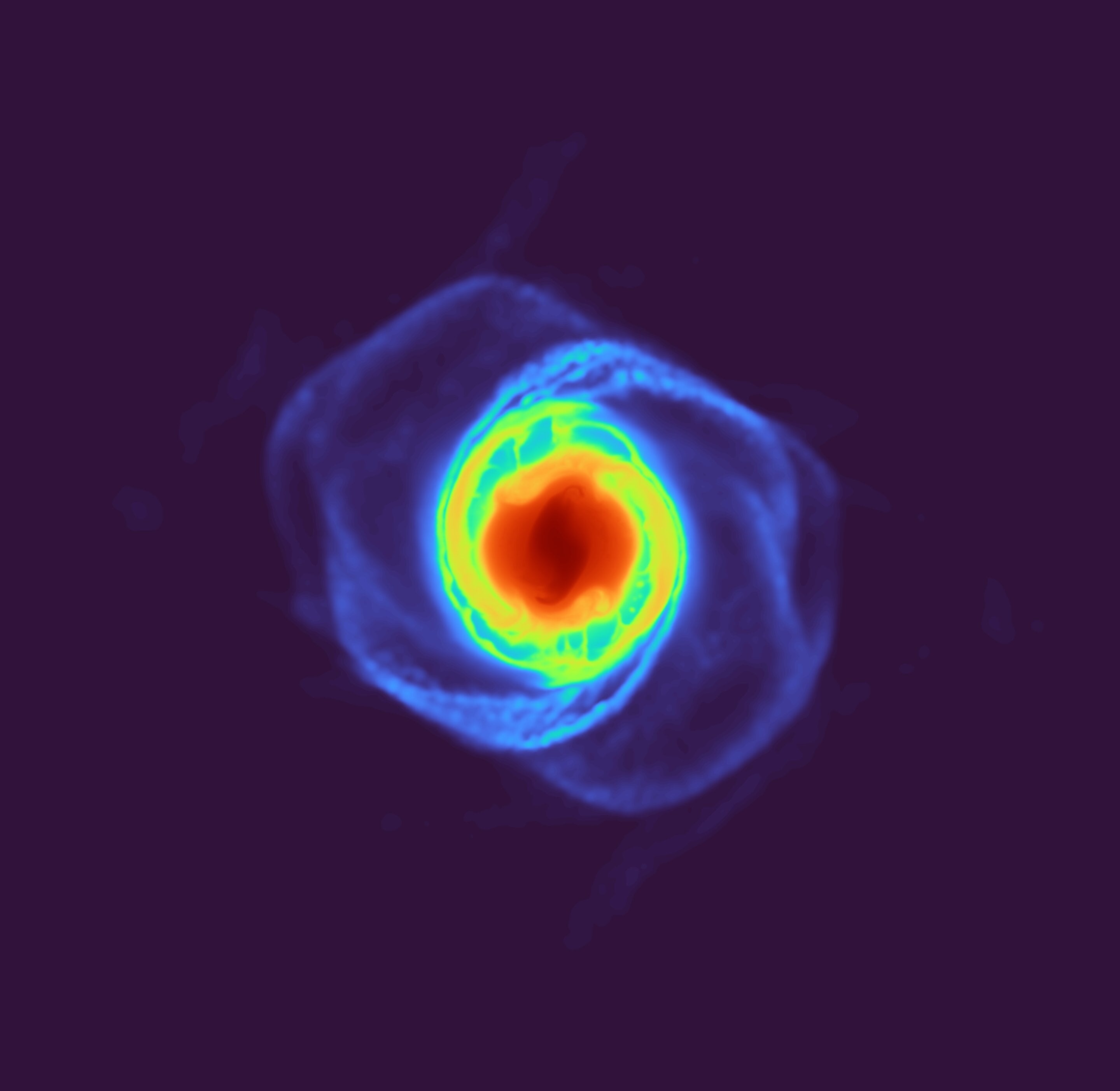

Astronomers have discovered an exoplanet called TOI-1853b, which is roughly the size of Neptune but has a density denser than solid steel. Located 545 light-years away, the planet orbits a K2 dwarf star and has a radius 3.5 times that of Earth, carrying approximately 73 Earth masses. Scientists believe that the planet was originally water-rich and underwent multiple high-velocity collisions, stripping away lighter elements and leaving behind only dense rocky material. This discovery highlights the diverse and strange nature of planets in the universe.

Astronomers have discovered a Neptune-sized planet, TOI-1853b, with a density higher than steel, suggesting it may have formed through giant planetary collisions. The planet's mass is almost twice that of any other similar-sized planet known, and its high density indicates a larger fraction of rock than expected. The study connects theories of planet formation in the solar system to the formation of exoplanets, providing new insights into the prevalence of giant impacts in planetary systems throughout the galaxy. Further observations will be conducted to examine the planet's residual atmosphere and composition.

The early universe did not collapse into a black hole because the creation of a black hole relies on not only incredibly high densities but also density differences. The early universe was incredibly dense, but it was dense everywhere, with barely any differences. Additionally, the early universe was dynamic, evolving, changing, and most importantly, expanding. The rules of black hole formation simply don't apply in an expanding universe. There wasn't enough mass in the universe to counteract the natural expansion of the universe and force it to collapse.

The early universe didn't collapse into a black hole despite its high density because there were not enough differences in density to trigger the formation of black holes. Additionally, the universe was dynamic and expanding, preventing all matter from collapsing. Black holes require a difference in density from place to place, and the early universe was incredibly uniform.

The early universe didn't collapse into a black hole because there was nothing to collapse into. To make a black hole, you need a difference in density from place to place. Even though the early universe was incredibly dense, it was also incredibly uniform. The expansion of the universe in its early days prevented all the matter from collapsing.

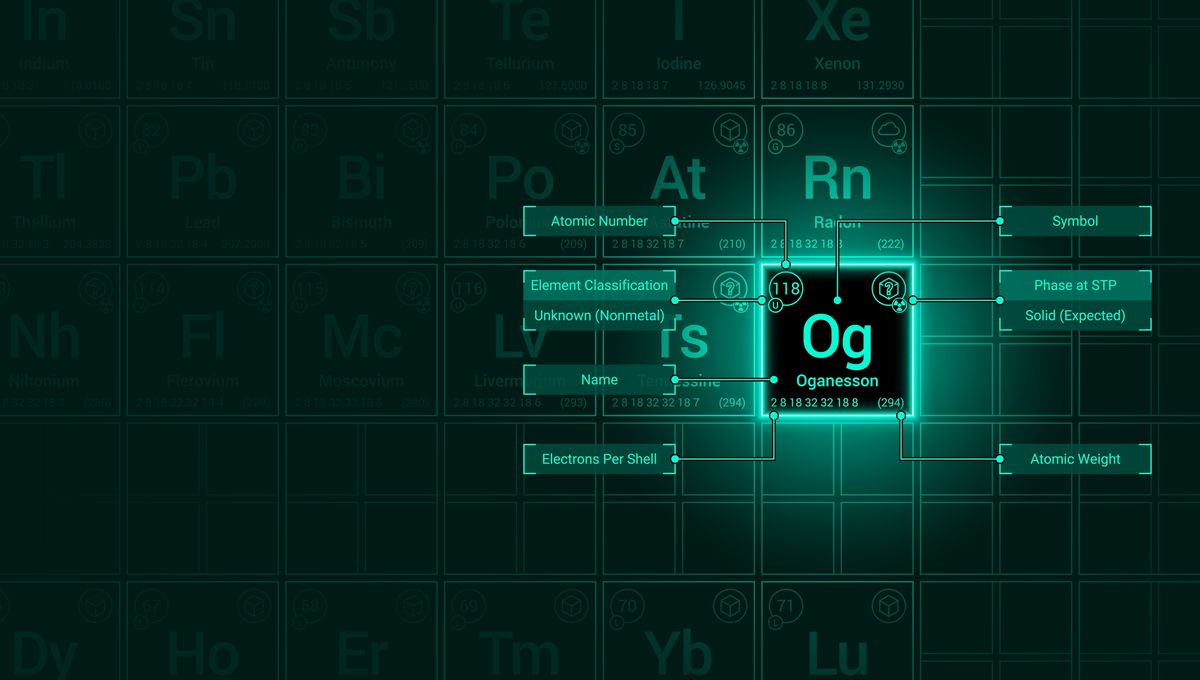

The heaviest element in the universe depends on how "heaviness" is defined. By atomic mass, oganesson is the heaviest element ever synthesized, with 118 protons and 176 neutrons. However, by natural occurrence, plutonium-244 is the heaviest element with 94 protons. Uranium-238 is the heaviest naturally occurring element with 92 protons. When considering density, osmium and iridium are the densest elements due to their high atomic mass and small atomic radius.