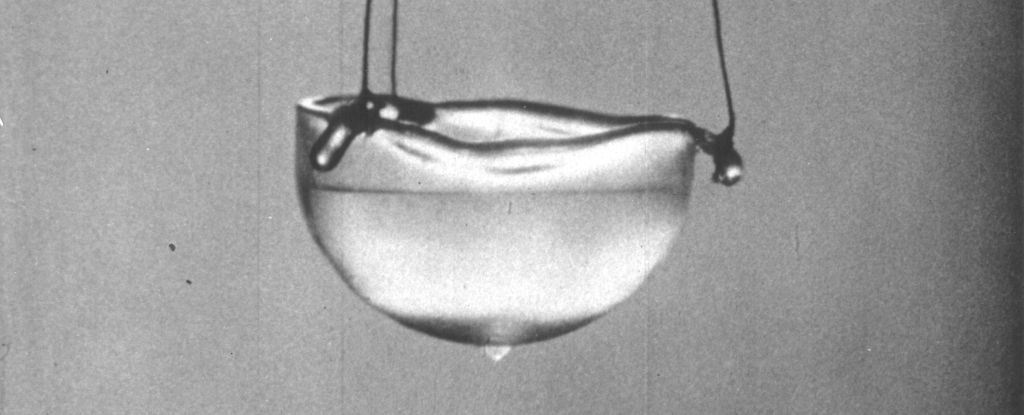

"MIT Physicists Capture First Images of Second Sound in Superfluid"

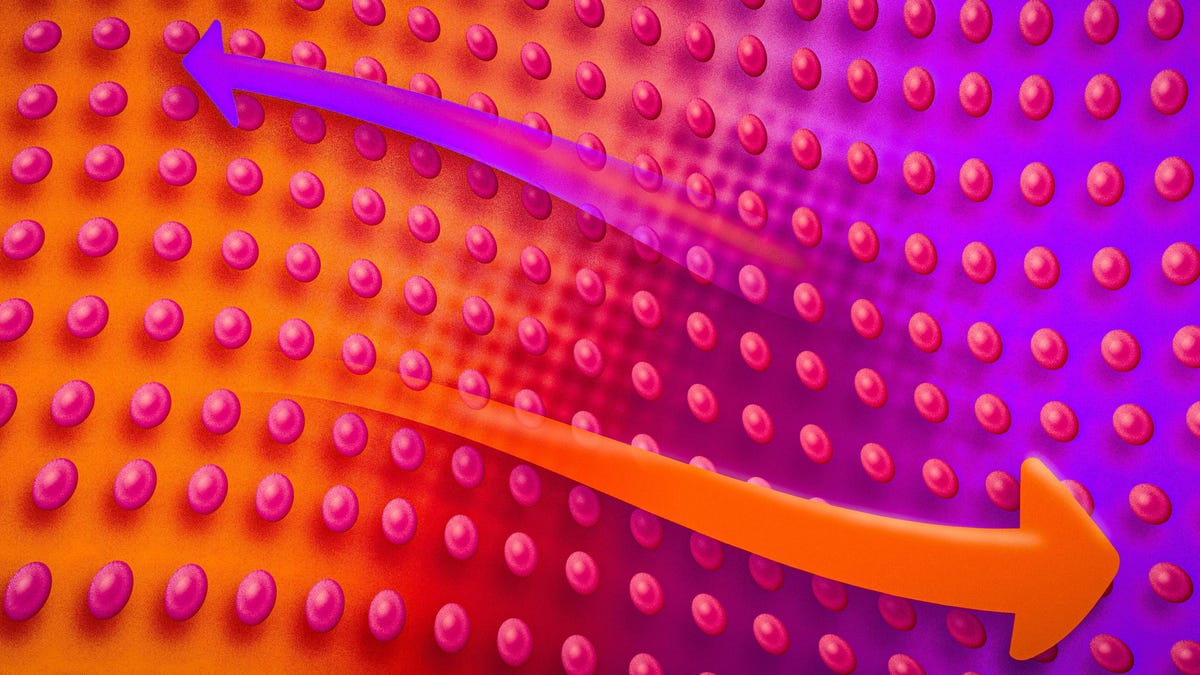

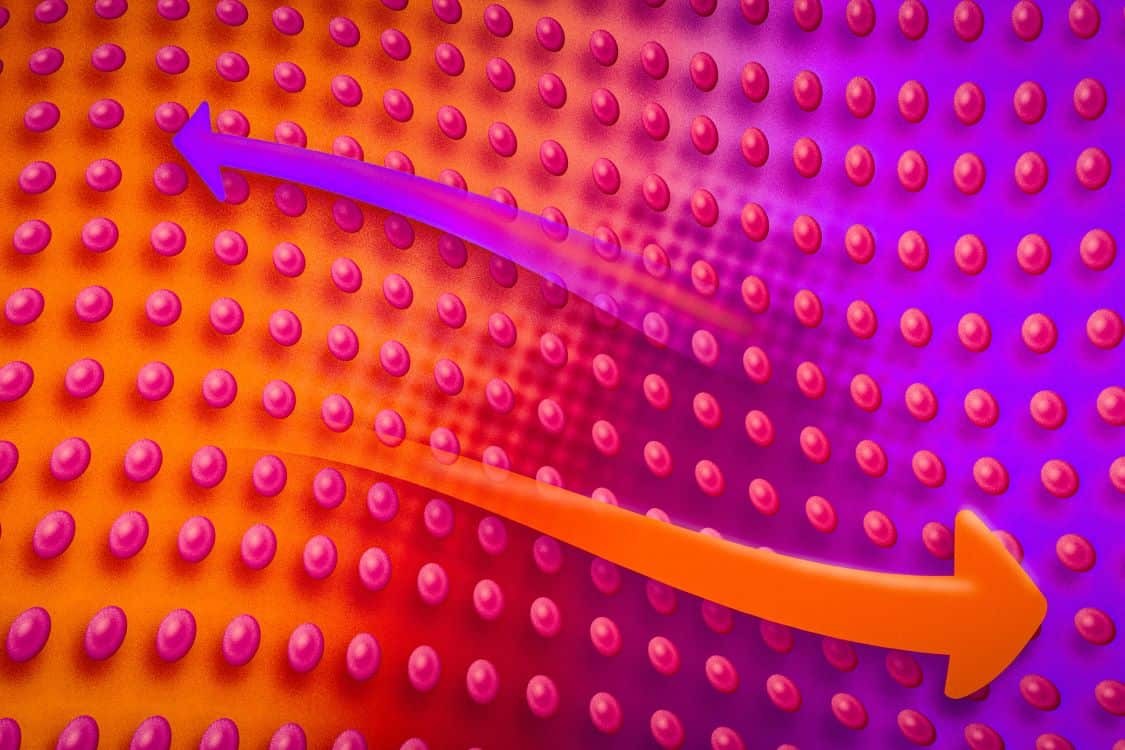

MIT physicists have captured direct images of "second sound," the movement of heat sloshing back and forth within a superfluid, for the first time. This breakthrough will expand scientists' understanding of heat flow in superconductors and neutron stars, and could lead to better-designed systems. The team visualized second sound in a superfluid by developing a new method of thermography using radio frequency to track heat's pure motion, independent of the physical motion of fermions. The findings will help physicists get a more complete picture of how heat moves through superfluids and other related materials.