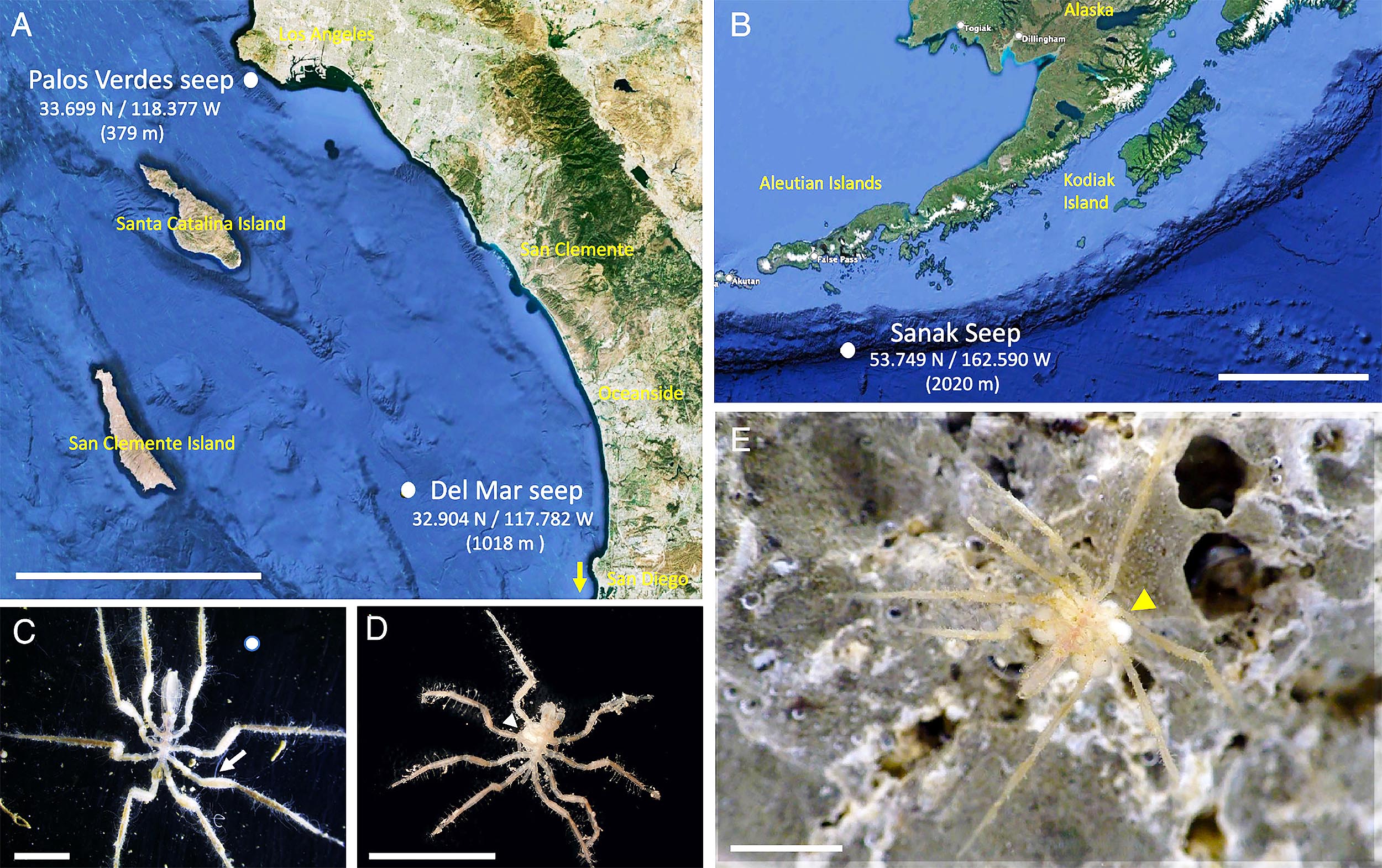

Sea Spiders Thrive in Darkness, Feed on Ocean Floor Methane

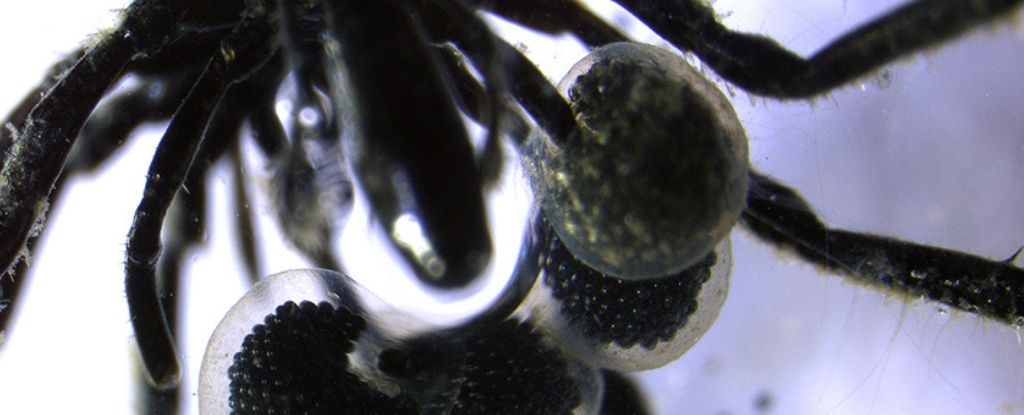

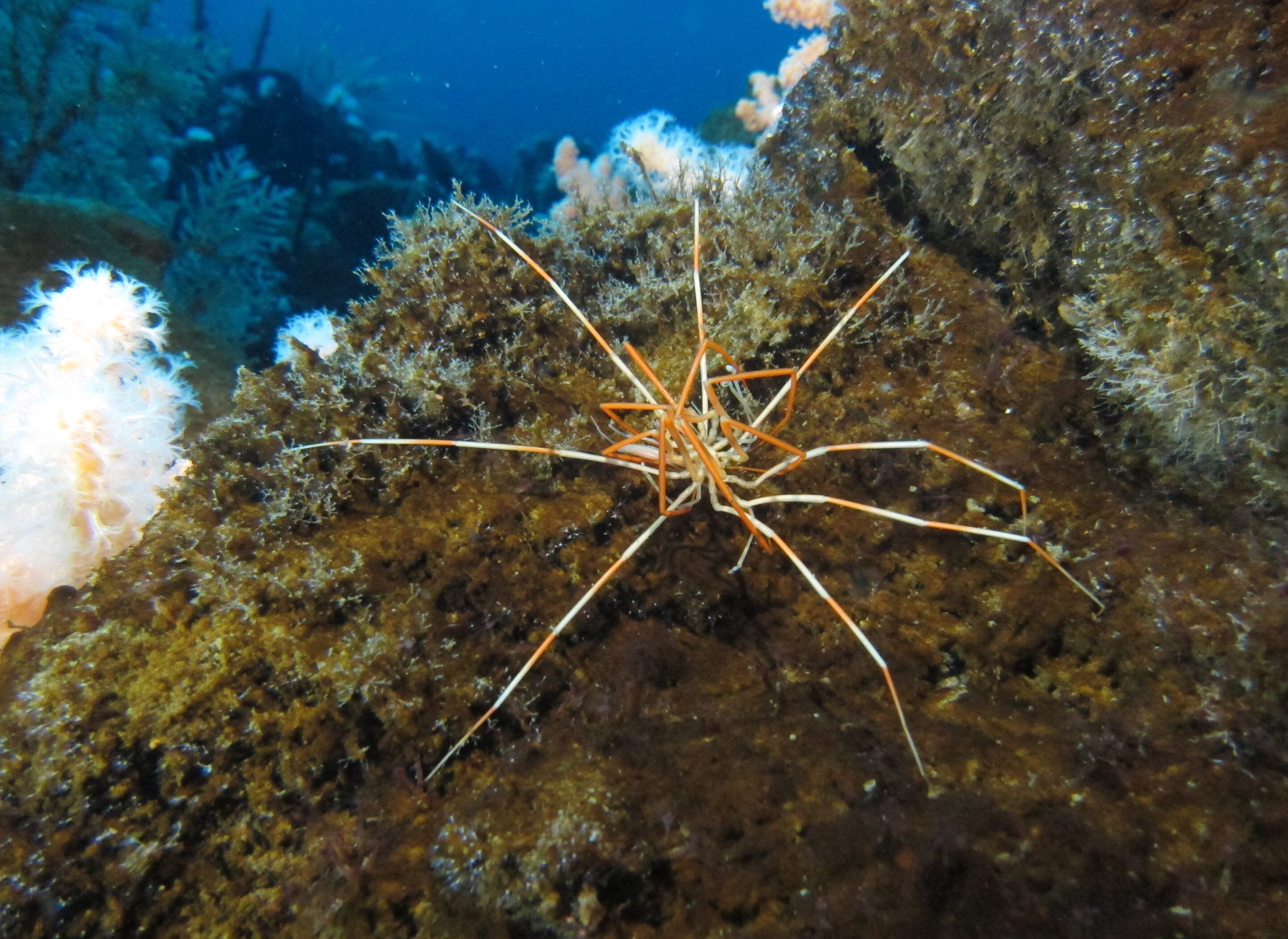

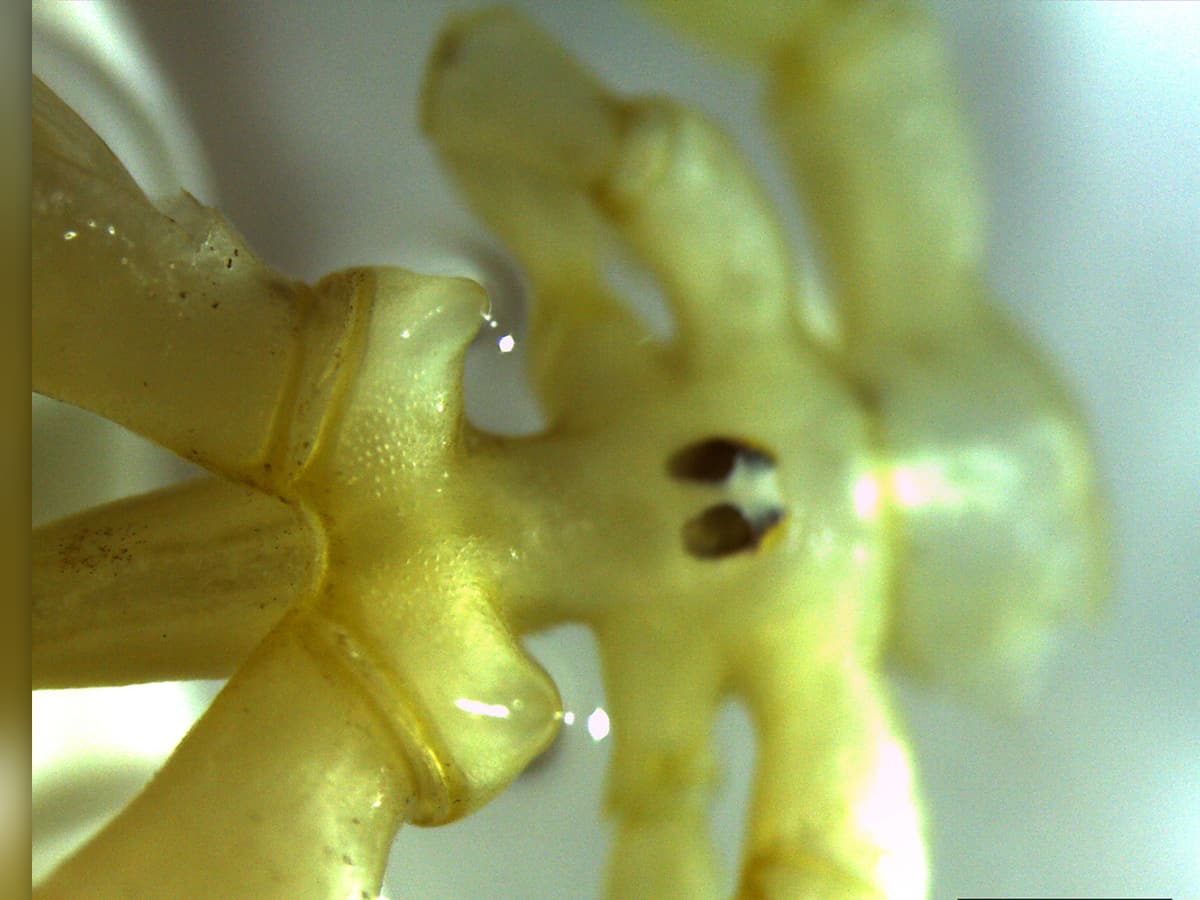

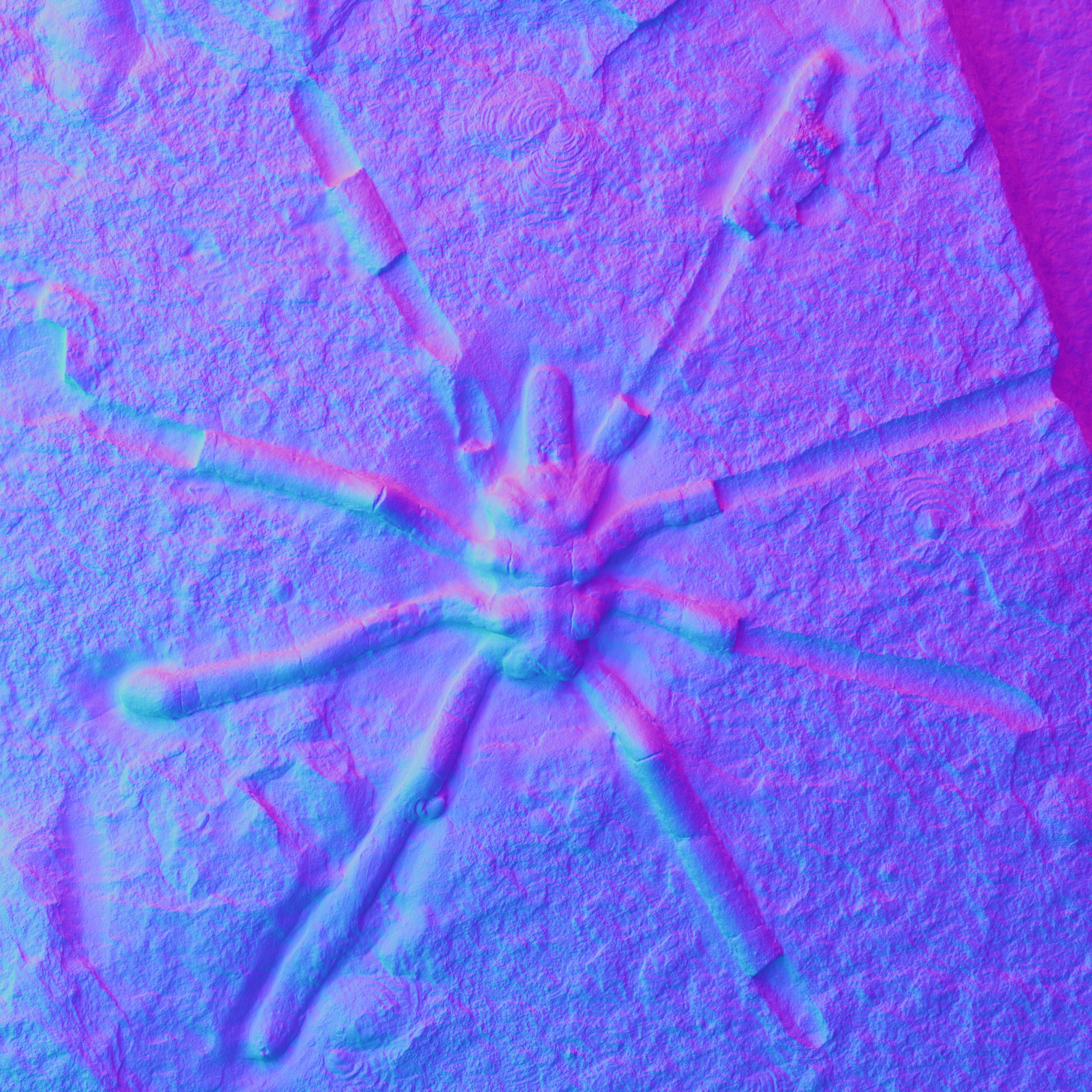

Scientists have discovered that sea spiders in deep California methane seeps thrive by cultivating and grazing on methane-consuming bacteria on their bodies, revealing a unique survival strategy and potential role in reducing methane emissions, with implications for understanding deep-sea microbial ecosystems and climate change mitigation.