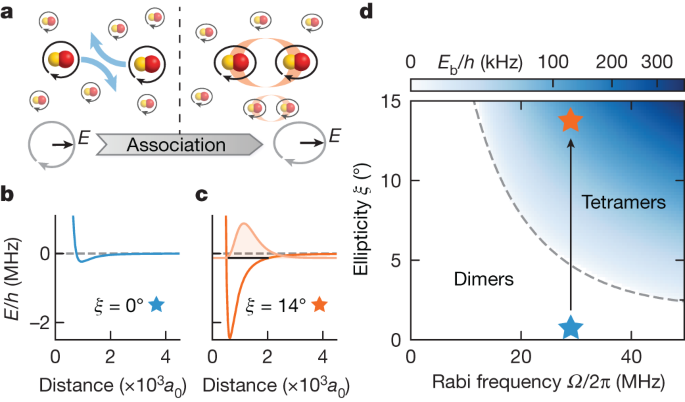

"Formation of Ultracold Field-Linked Tetratomic Molecules"

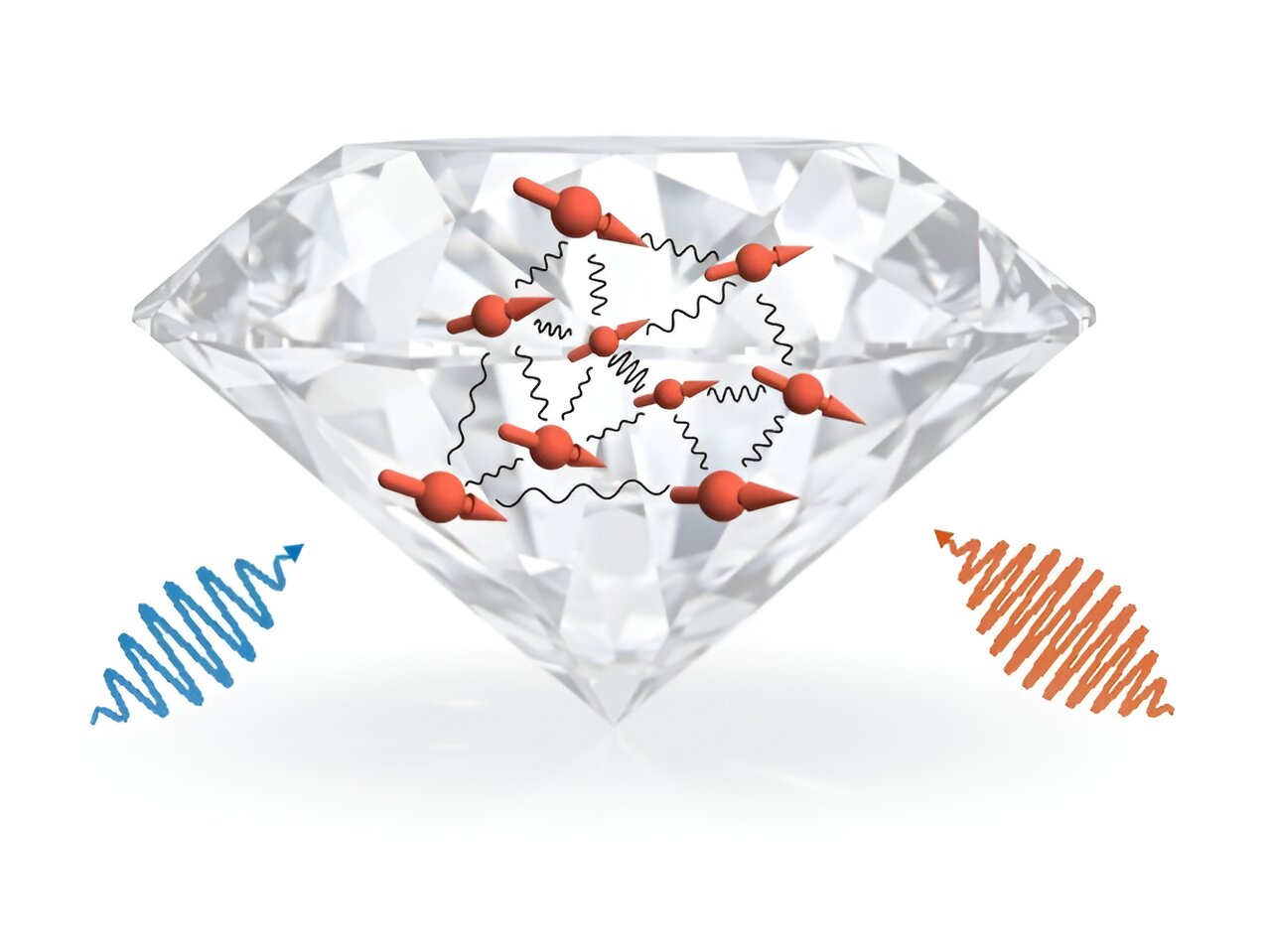

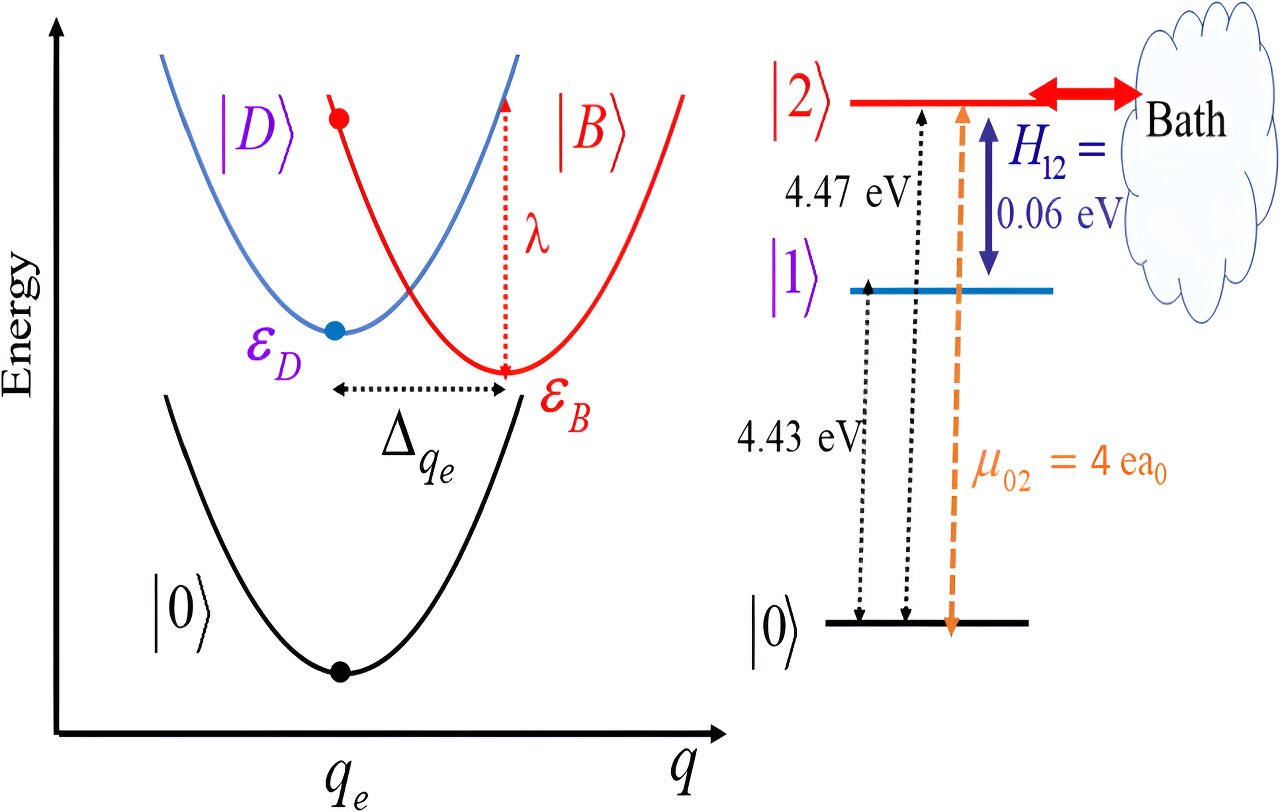

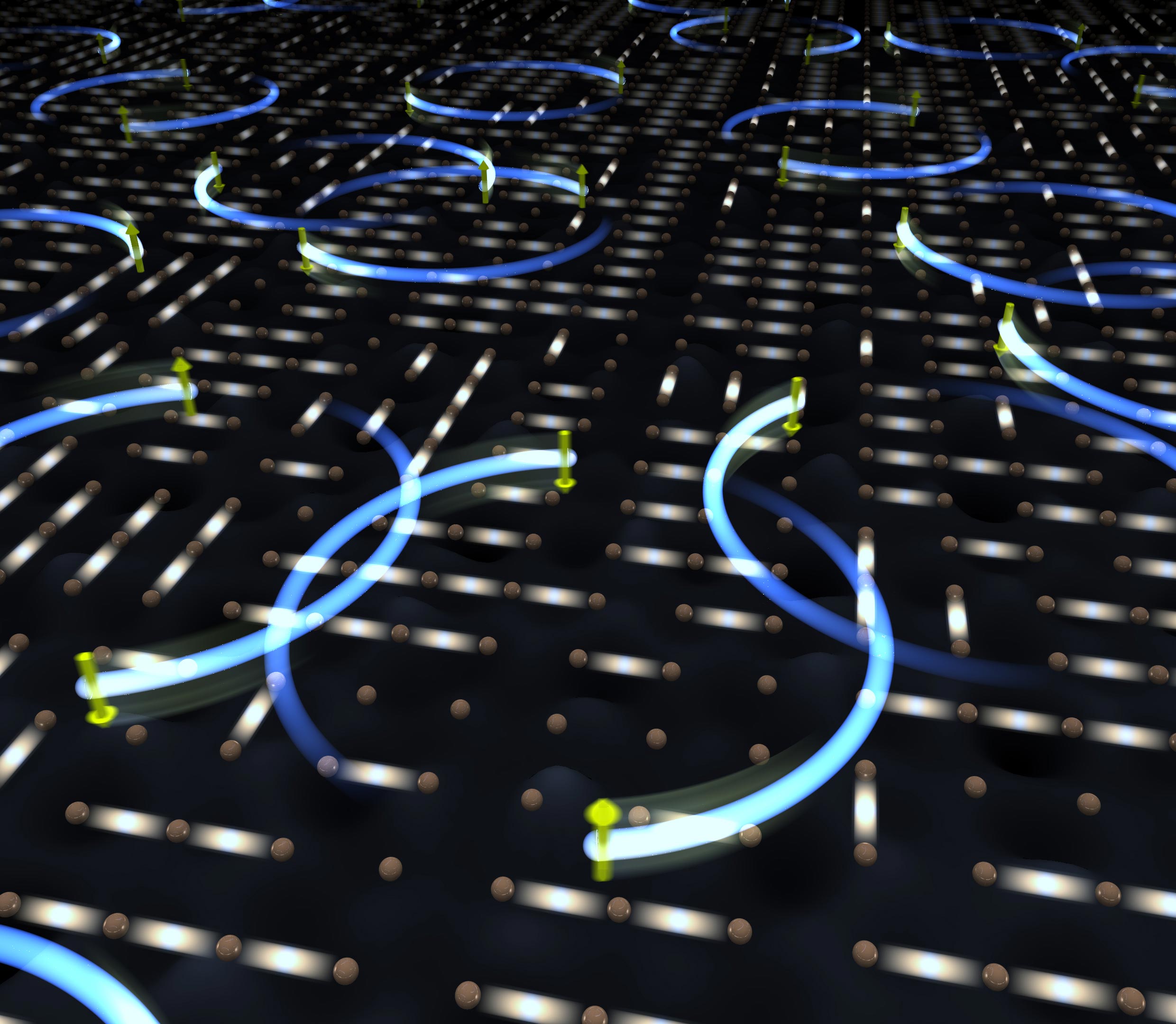

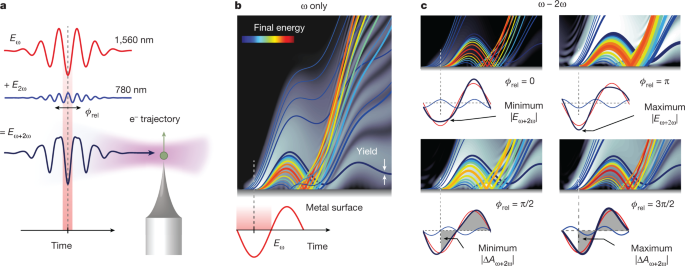

Researchers have demonstrated a new method to create weakly bound ultracold tetratomic molecules by electroassociating pairs of fermionic NaK molecules in microwave-dressed states. These tetratomic molecules are created at ultracold temperatures and exhibit highly tunable properties with the microwave field. The approach can be applied to a wide range of polar molecules and opens up possibilities for investigating quantum many-body phenomena.