Revolutionary Super-Resolution X-Ray Technique Unveils Atomic Details

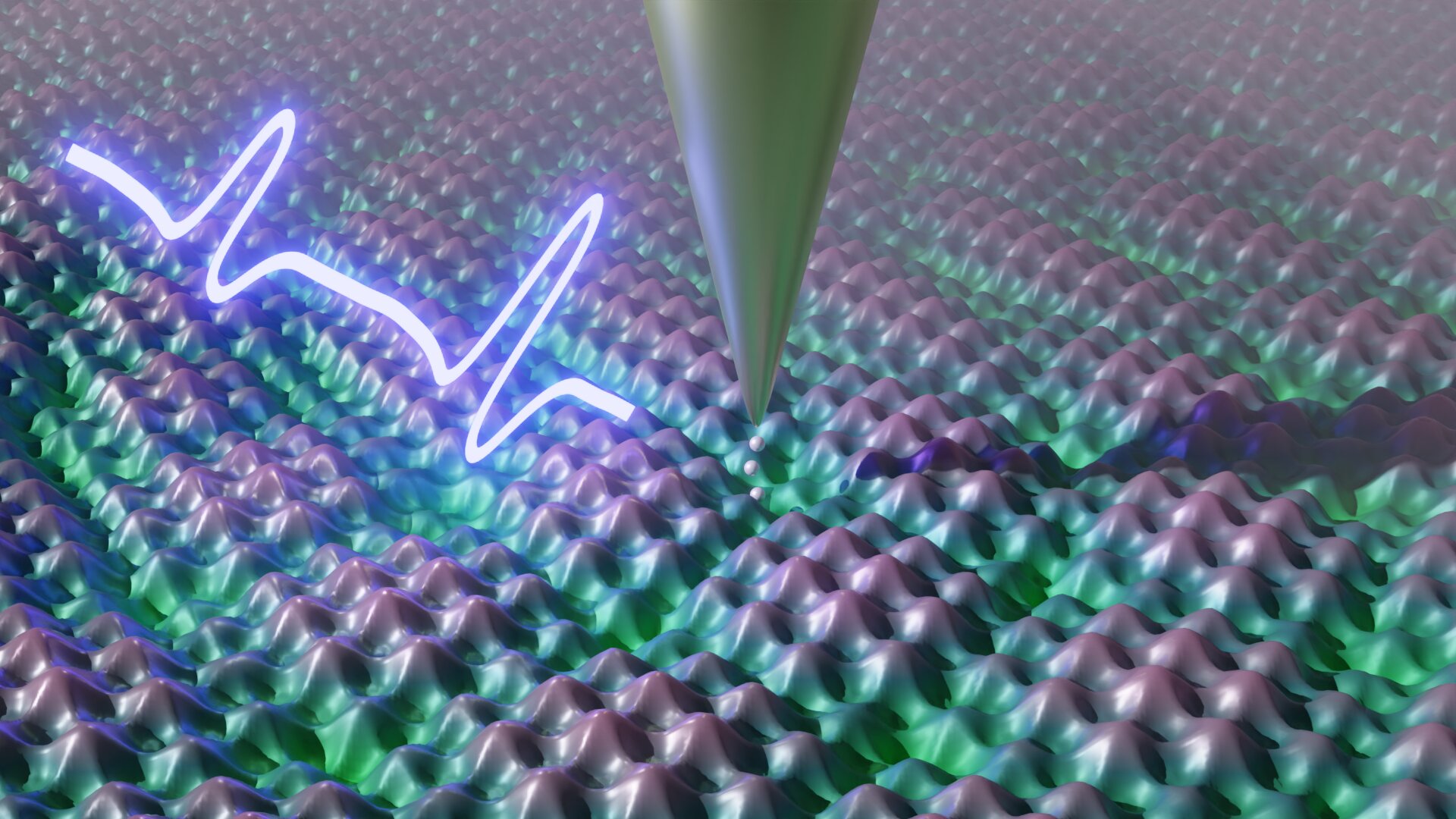

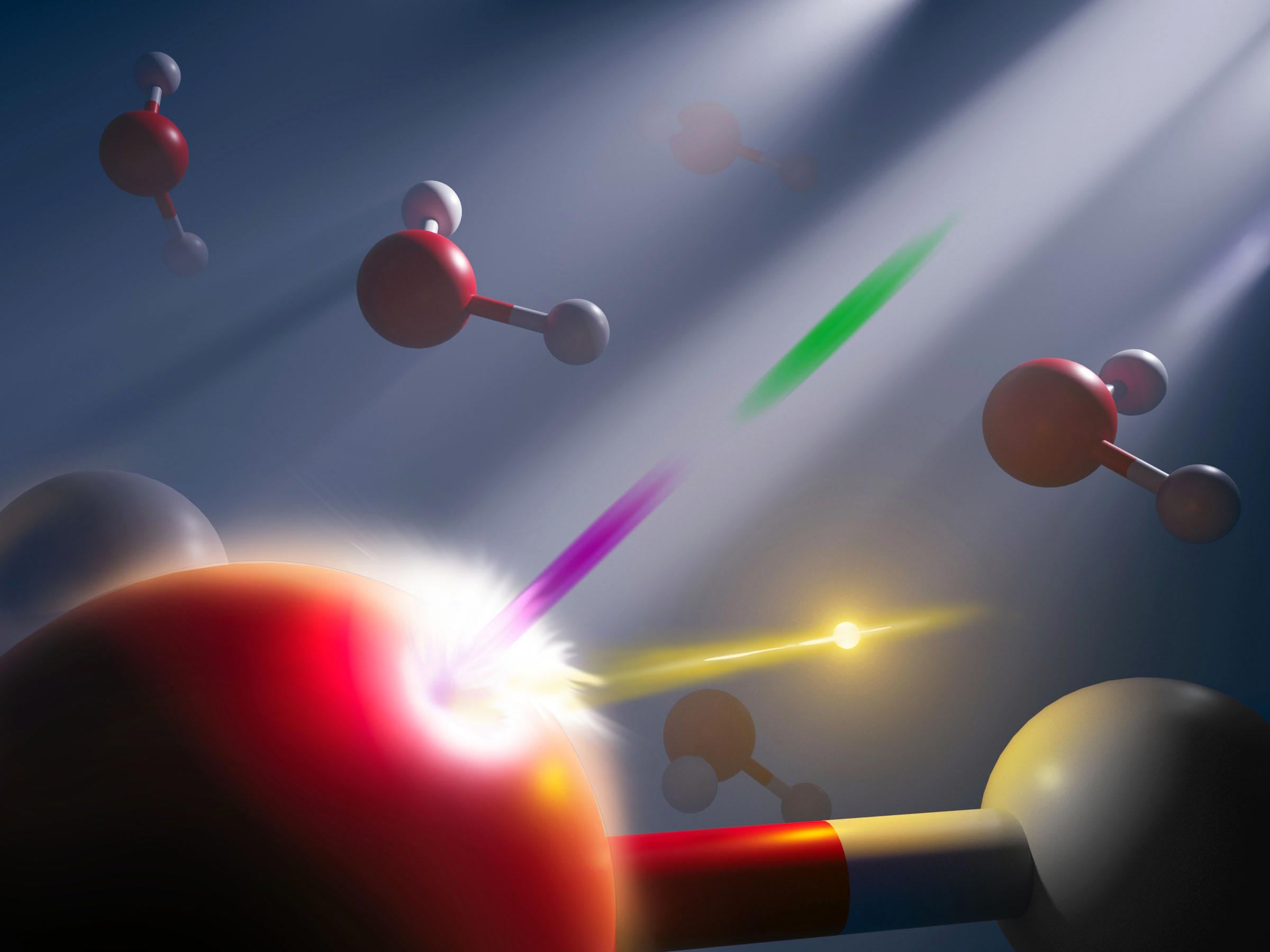

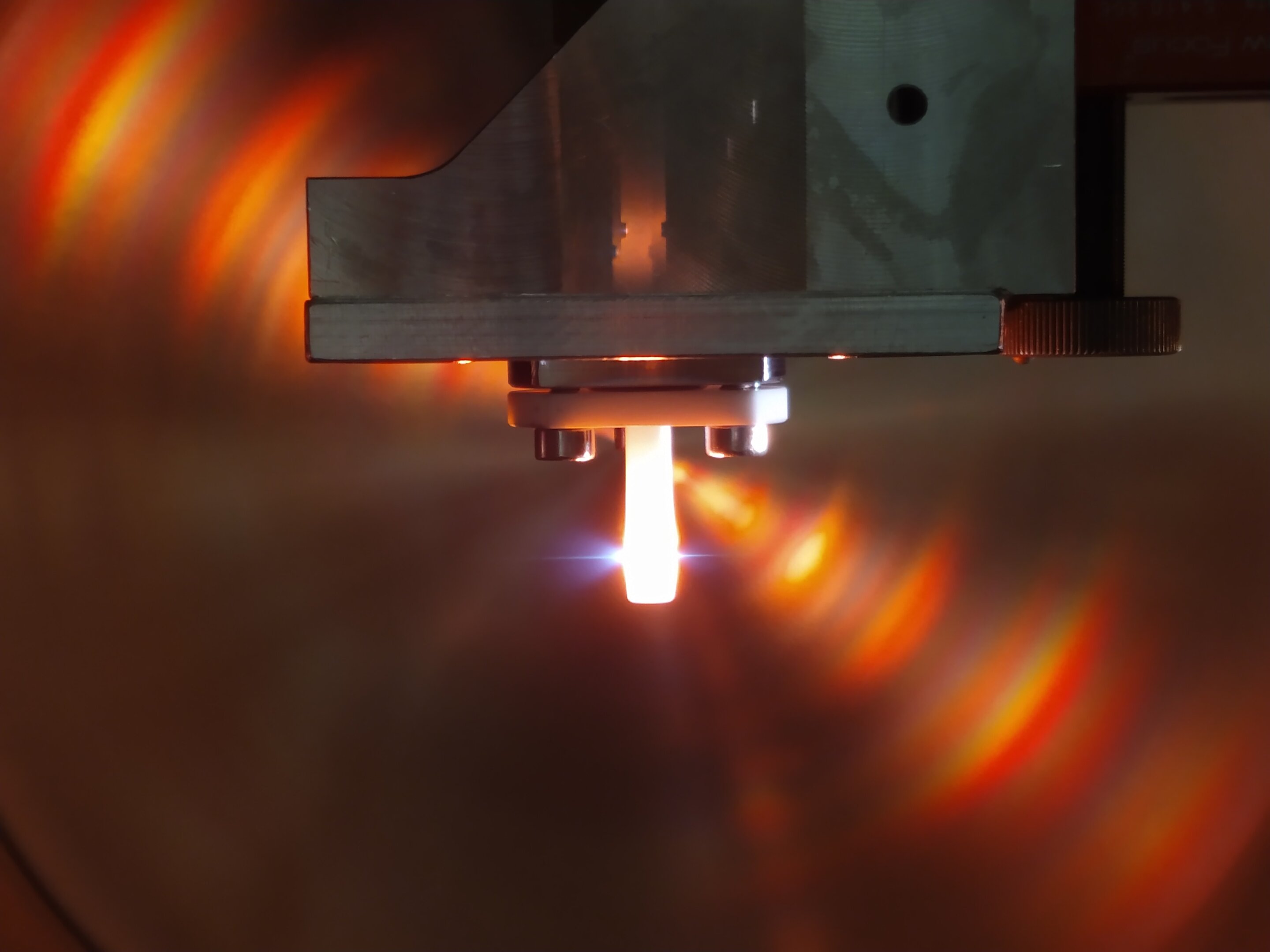

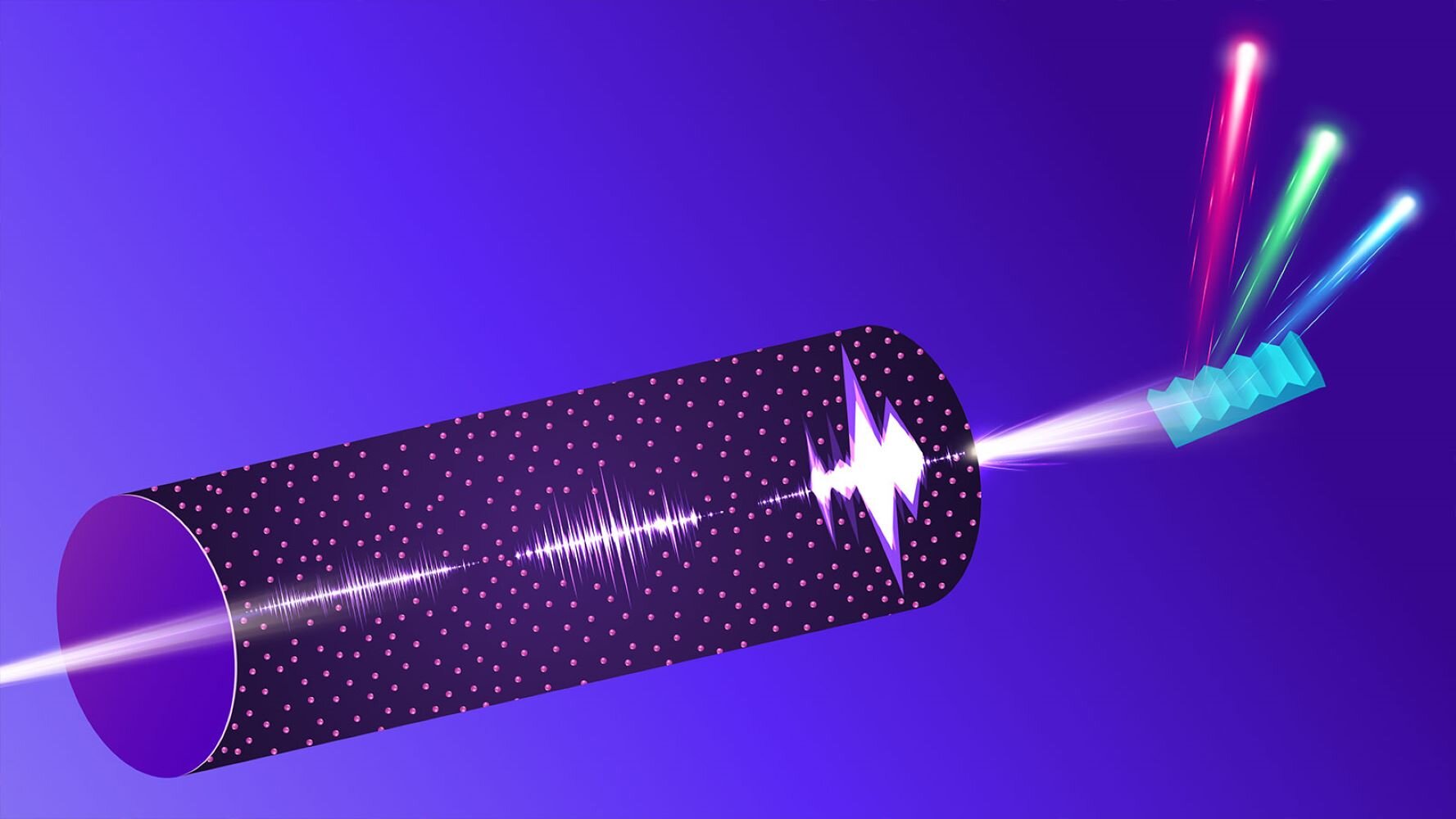

Researchers have developed a novel X-ray technique called stochastic Stimulated X-ray Raman Scattering (s-SXRS) that uses noise to achieve unprecedented resolution in atomic and electronic structure imaging, enabling detailed insights into chemical reactions and material properties, with potential widespread applications in science and industry.