"Teaching AI Language Acquisition Through a Baby's Eyes"

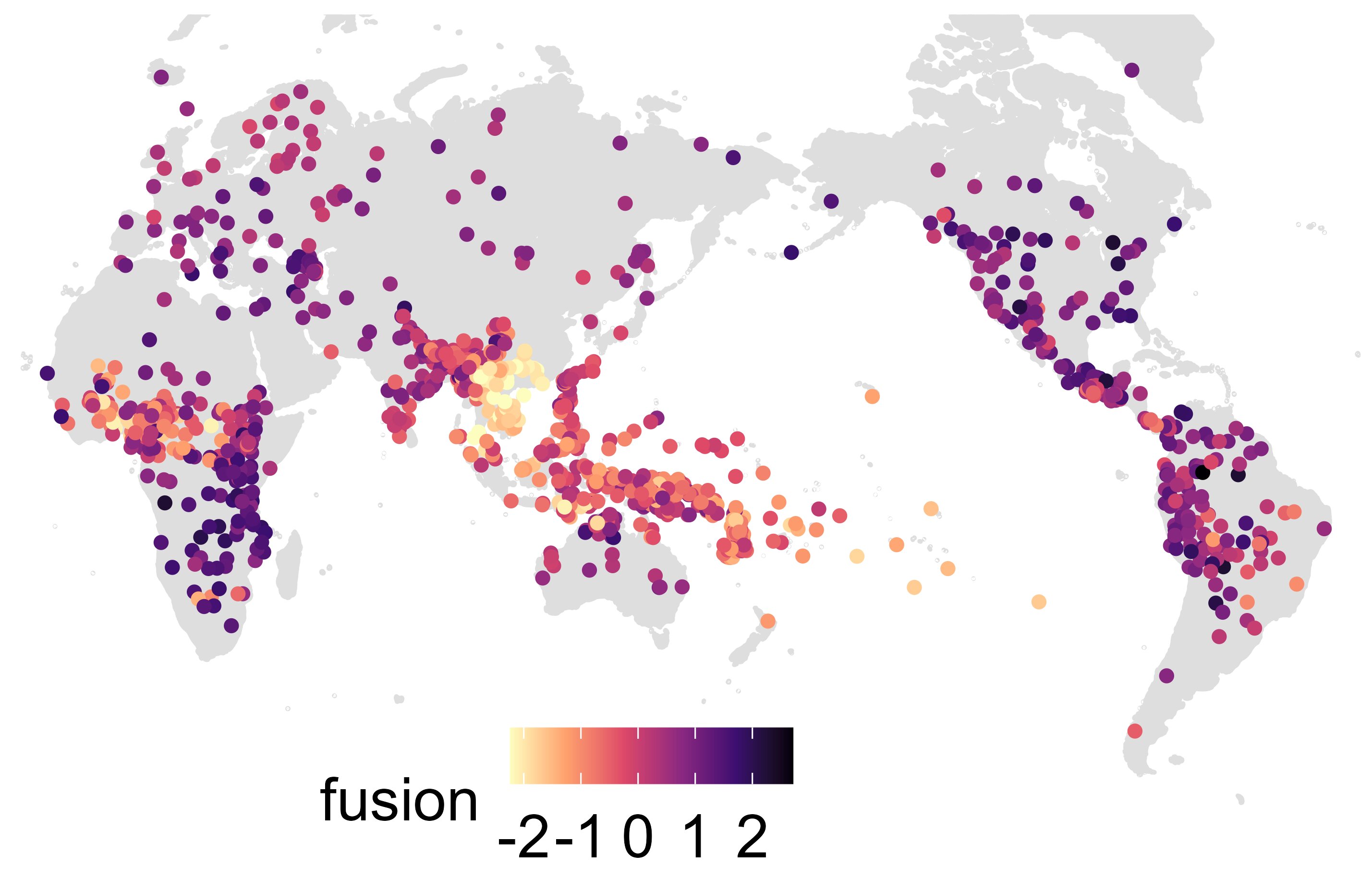

Scientists have used a baby's experiences captured through a headcam to train an AI program to understand language acquisition. The AI, given a fraction of the child's experiences, learned to match words with images, demonstrating that language learning can occur from sensory input. This research is part of a larger effort to develop AI that mimics a baby's learning process and could lead to more intuitive AI teaching methods. However, the AI's abilities still fall short of a child's language learning, and further research is needed to understand how children actually learn language.