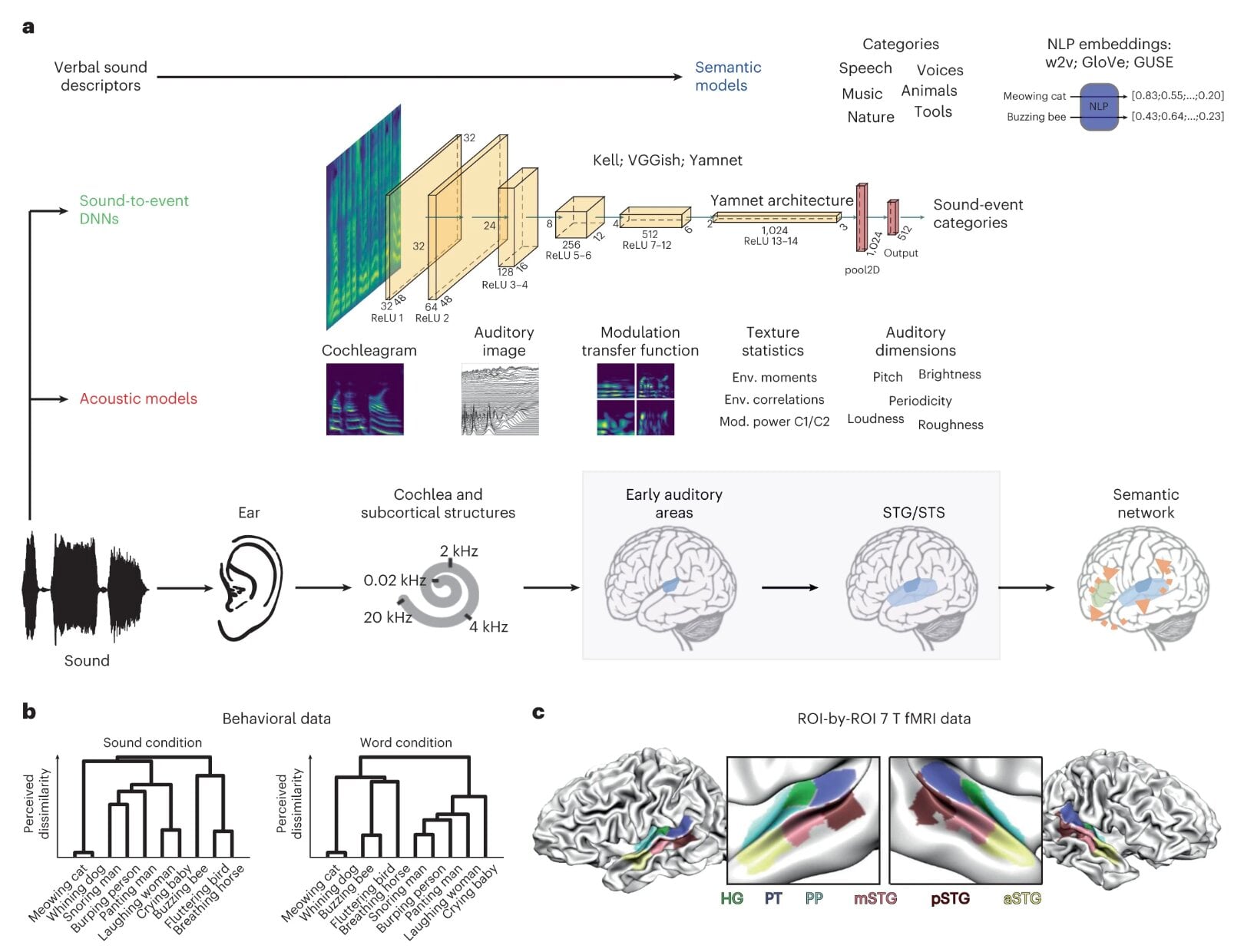

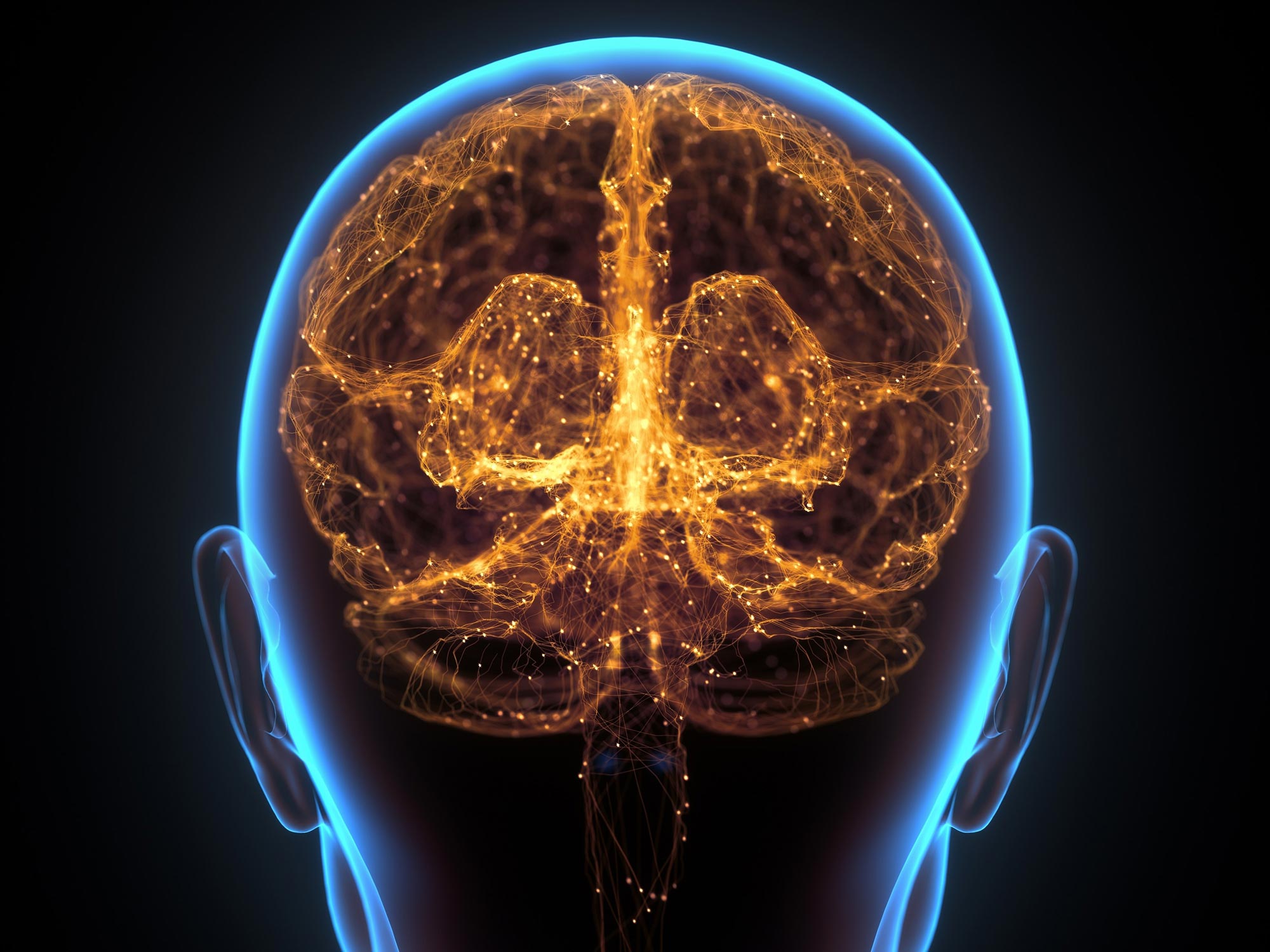

"Universal Brain Structure Laws Span Species, Study Finds"

Researchers at Northwestern University have found that the structural features of brains from humans, mice, and fruit flies are near a critical point similar to a phase transition, suggesting a universal principle may govern brain structure. This discovery could lead to new computational models that emulate brain complexity, as the brain's structure appears to be in a delicate balance between two phases, exhibiting fractal-like patterns and other hallmarks of criticality.