Mental 'Time Travel' Technique Enhances Memory Recall and Restoration

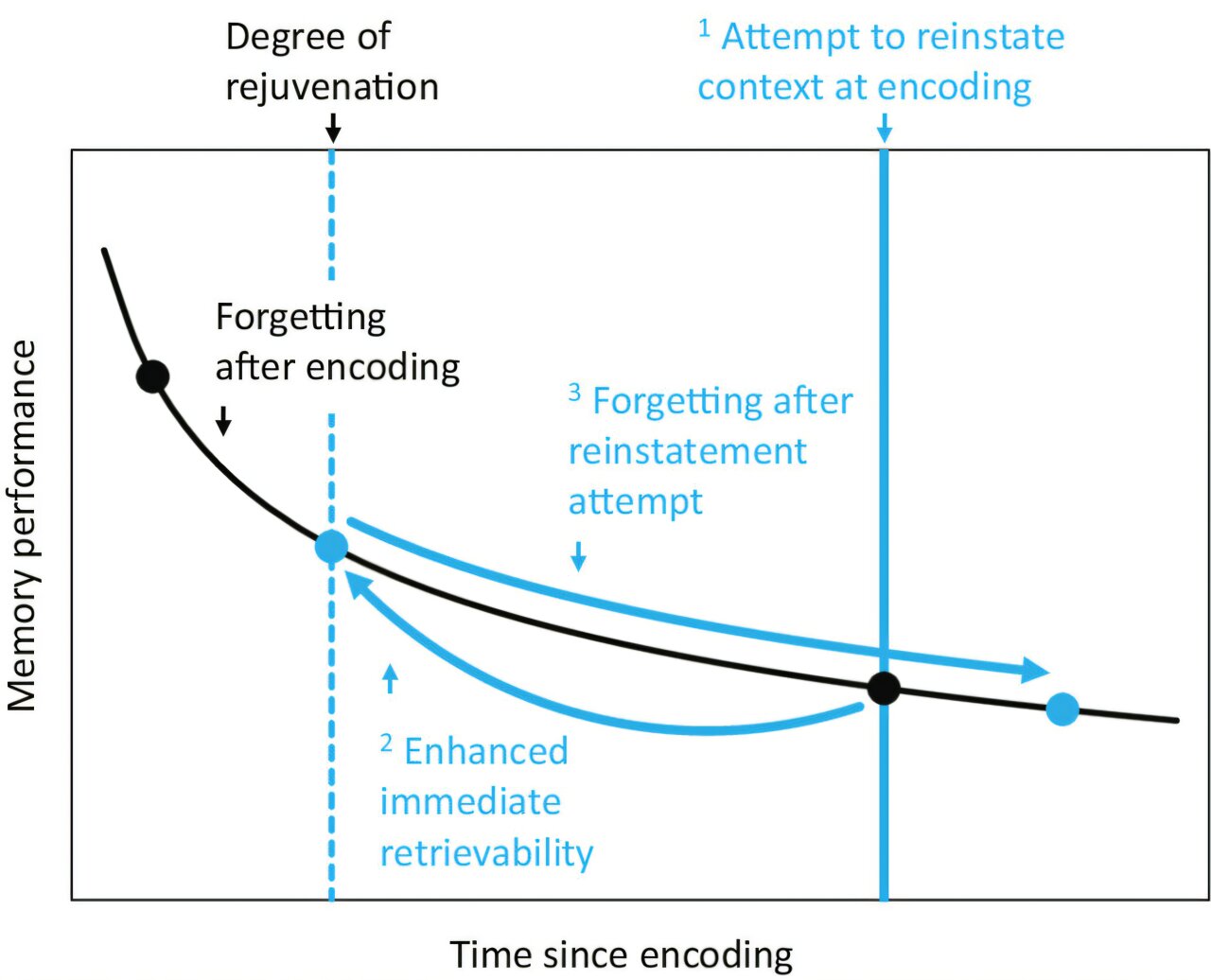

A new study suggests that mentally revisiting the context of past memories can temporarily restore their retrievability and reverse the typical forgetting curve, especially when done within a few days of encoding, offering hope for memory recovery but requiring further research for real-life applications.