"Unraveling the 1.6 Million-Year-Old Mystery of Human Language Evolution"

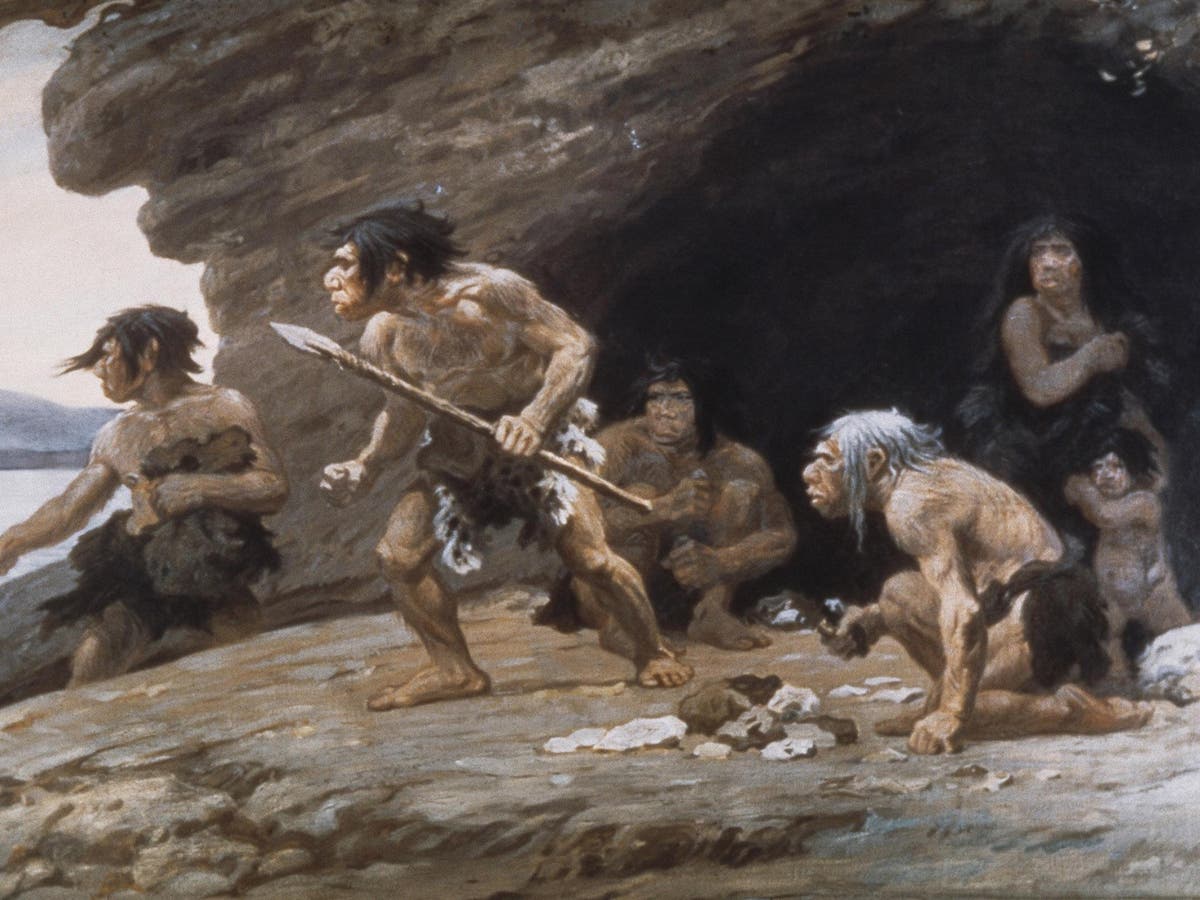

New research by British archaeologist Steven Mithen suggests that early humans likely developed rudimentary language around 1.6 million years ago in eastern or southern Africa, challenging the previous belief that humans only started speaking around 200,000 years ago. The analysis is based on a comprehensive study of archaeological, genetic, neurological, and linguistic evidence, indicating that the birth of language was part of a suite of human evolution and other developments between two and 1.5 million years ago. The emergence of language was linked to improvements in working memory and was crucial for facilitating group planning and coordination abilities, particularly in hunting and survival. This new research also suggests that some aspects of the first linguistic development 1.6 million years ago may still survive in modern languages today.