"Flat Protoplanets: A Surprising Twist in Gas Giant Formation"

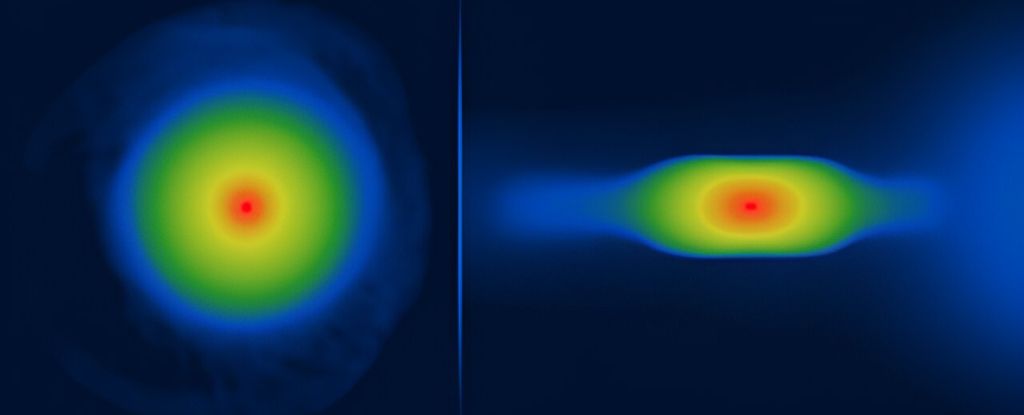

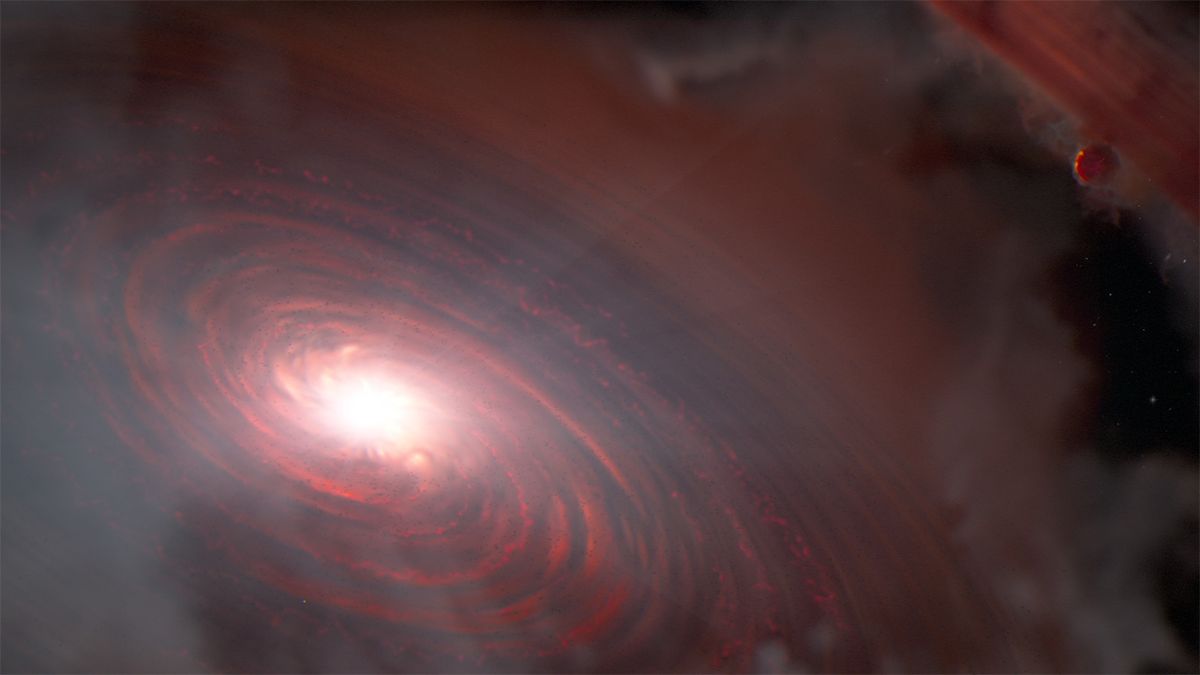

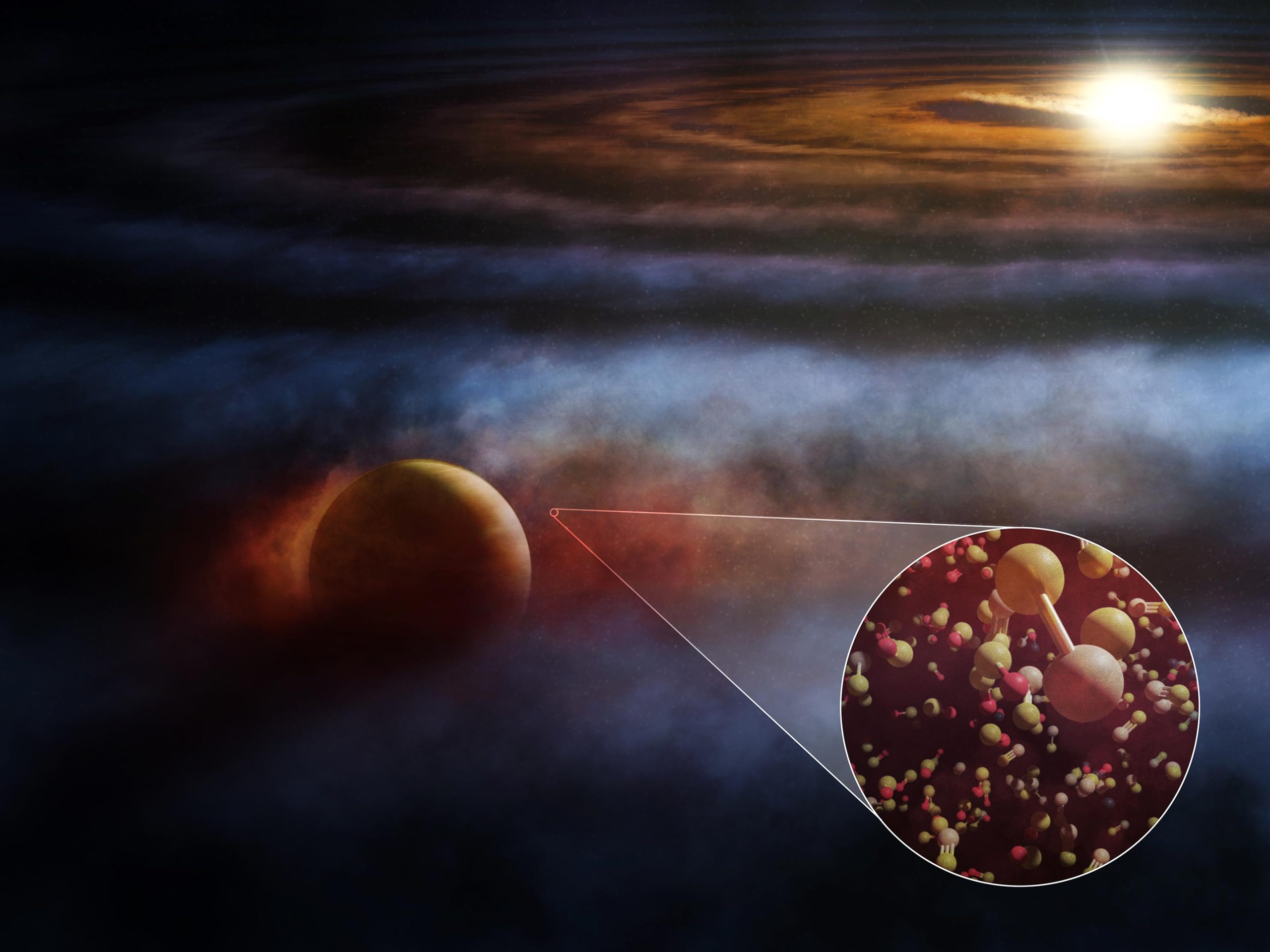

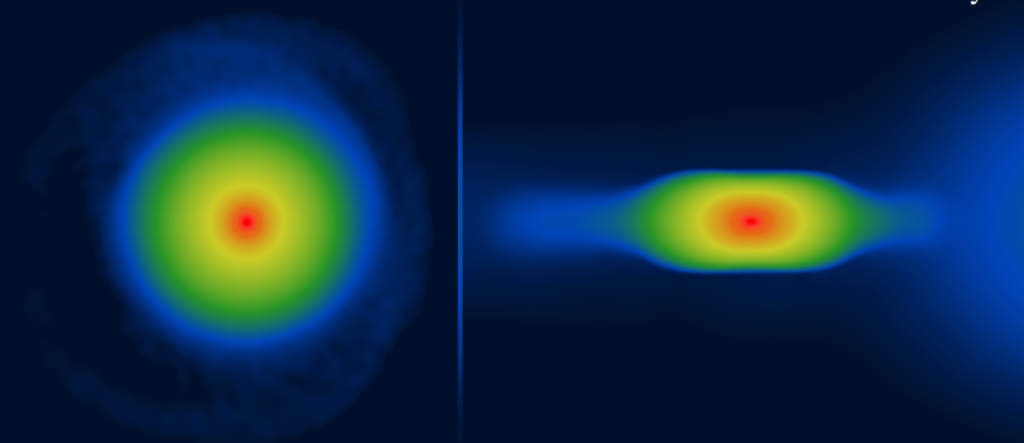

New modelling suggests that protoplanets formed within fragmentary protostar accretion discs may take on a strongly oblate spheroid shape rather than a spherical one, based on simulations run by researchers at the University of Central Lancashire. This research not only enhances our understanding of our own solar system's formation, including Earth's oblate spheroid shape, but also aids in interpreting observations from telescopes like Hubble and James Webb as we study actively forming star regions like the Orion Nebula, potentially refining simulations and reevaluating previous observational interpretations.