Microbiome Dynamics: Ecological Competition and Strain Displacement

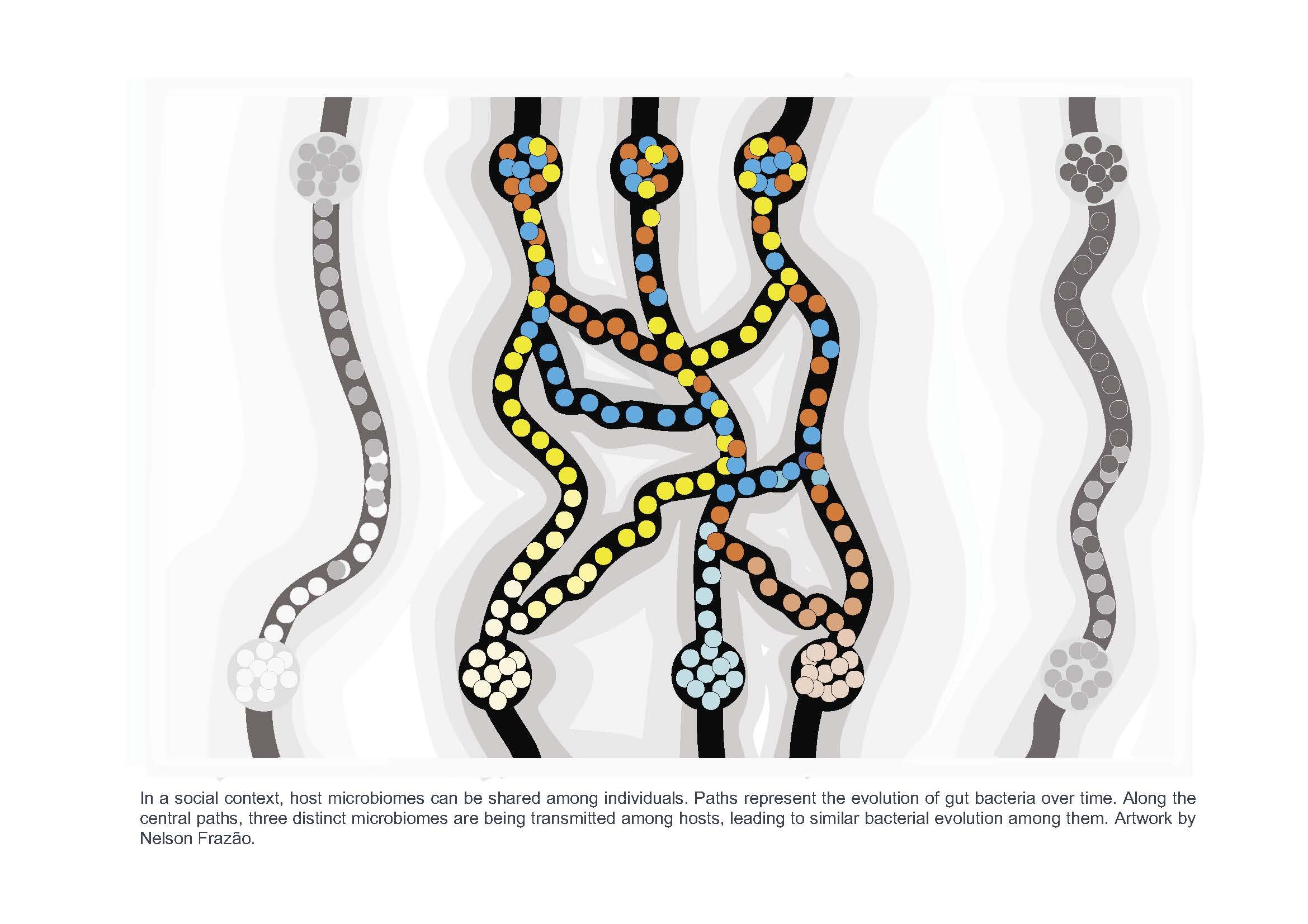

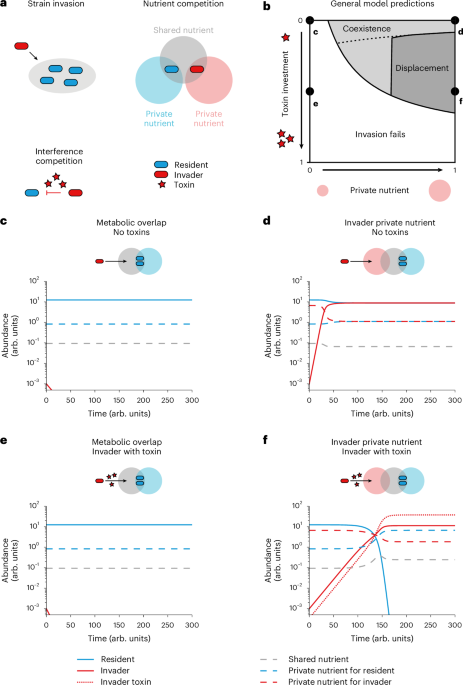

The article explores how ecological competition, including nutrient and interference competition via bacterial toxins, influences strain displacement in microbiomes, supported by mathematical modeling and experiments with engineered and natural E. coli strains, highlighting the importance of private nutrients and interference mechanisms for successful invasion and displacement within diverse bacterial communities.