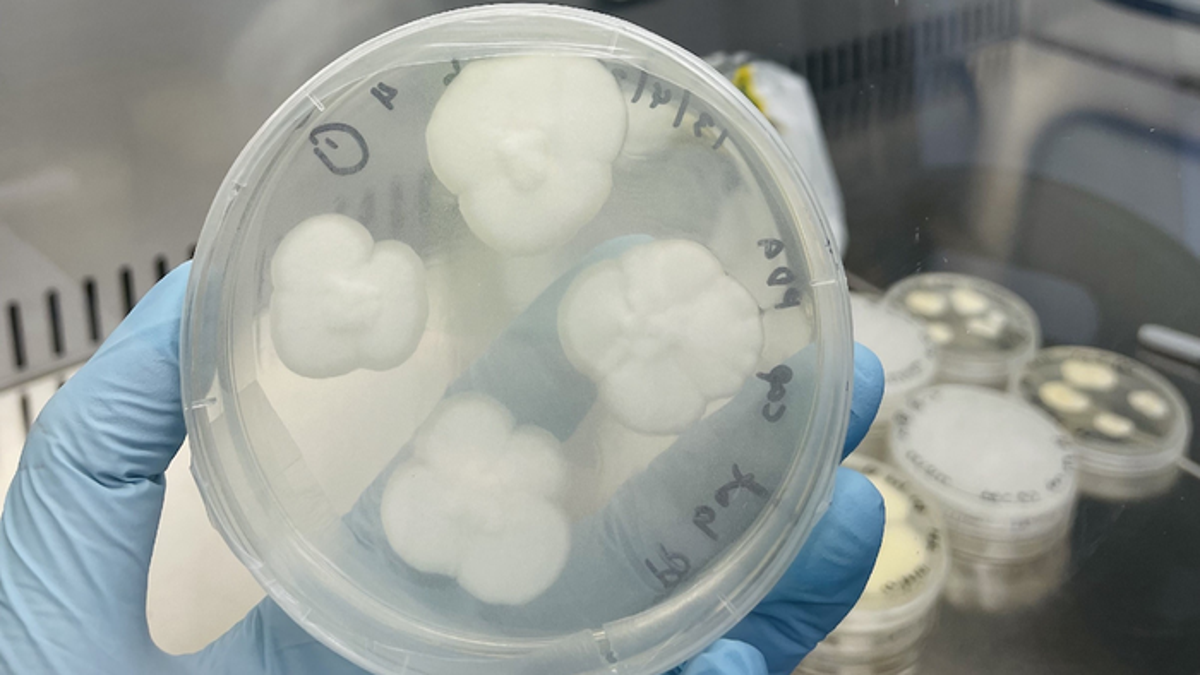

Plastic-Eating Caterpillars Turn Trash Into Body Fat

Waxworms can eat and break down plastic, specifically polyethylene, thanks to enzymes in their saliva, and they store the plastic as body fat. However, a diet solely of plastic shortens their lives and reduces their mass, making them unsuitable for direct environmental cleanup. Researchers see potential in re-engineering their plastic-degrading pathways or using them in controlled, co-supplemented environments for plastic waste management and possibly producing insect biomass for commercial use.