Cancer hijacks immune cell mitochondria to boost spread and dodge defenses

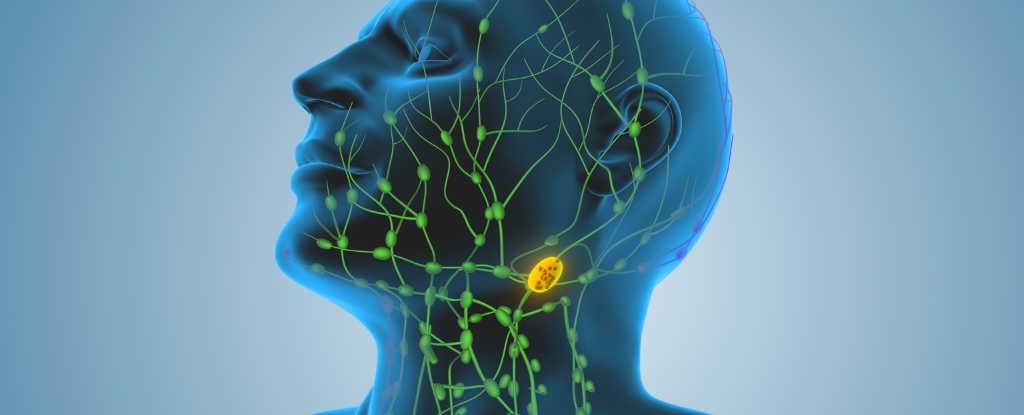

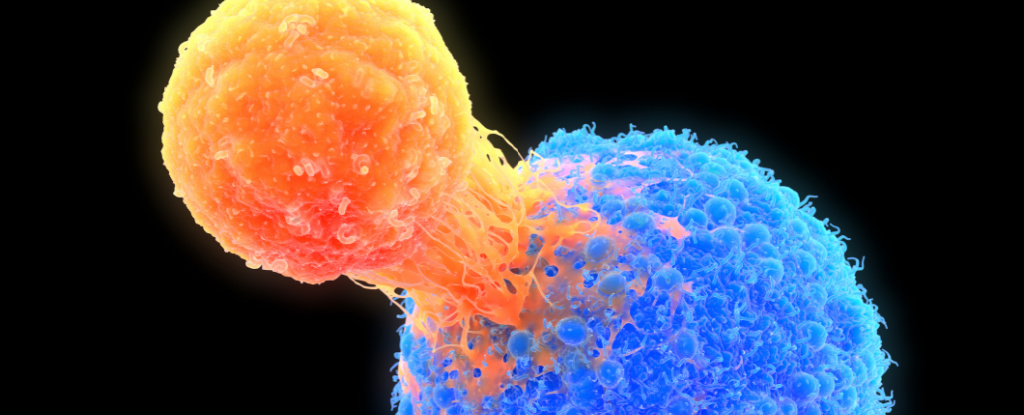

In mice, cancer cells acquire mitochondria from immune cells, weakening those cells and activating a type I interferon program in the cancer cells that promotes lymph‑node invasion. Blocking this pathway reduces spread, and the effect occurs even when the stolen mitochondria can’t produce ATP, indicating energy production isn’t required for this mechanism.