"Experimental Evidence of Graviton-Like Particles Connecting Quantum Mechanics and Relativity"

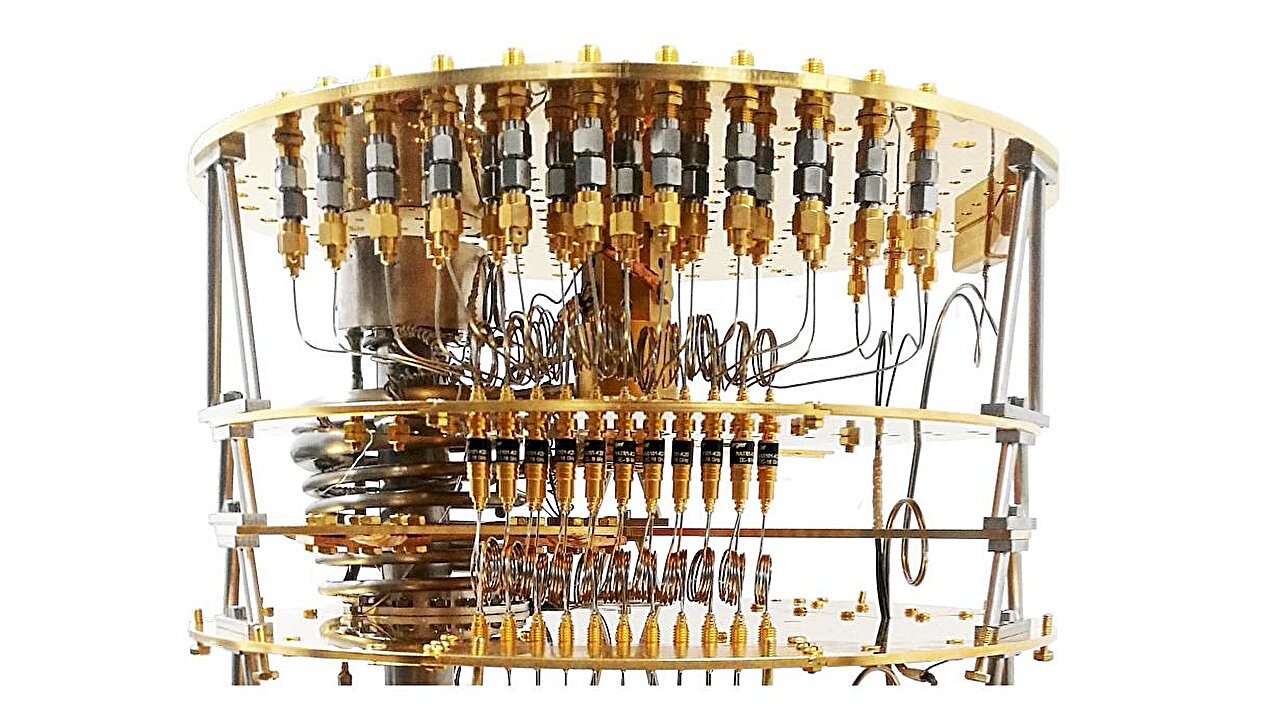

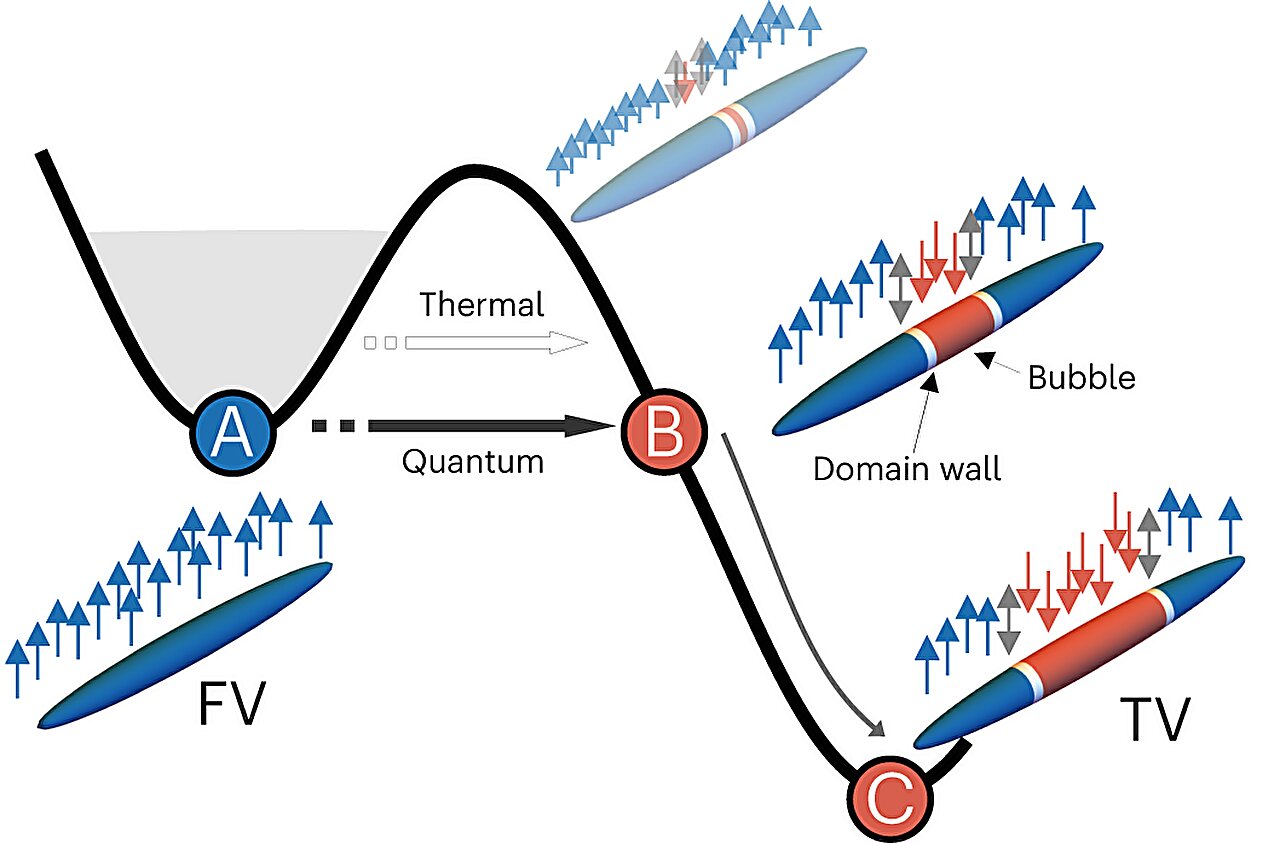

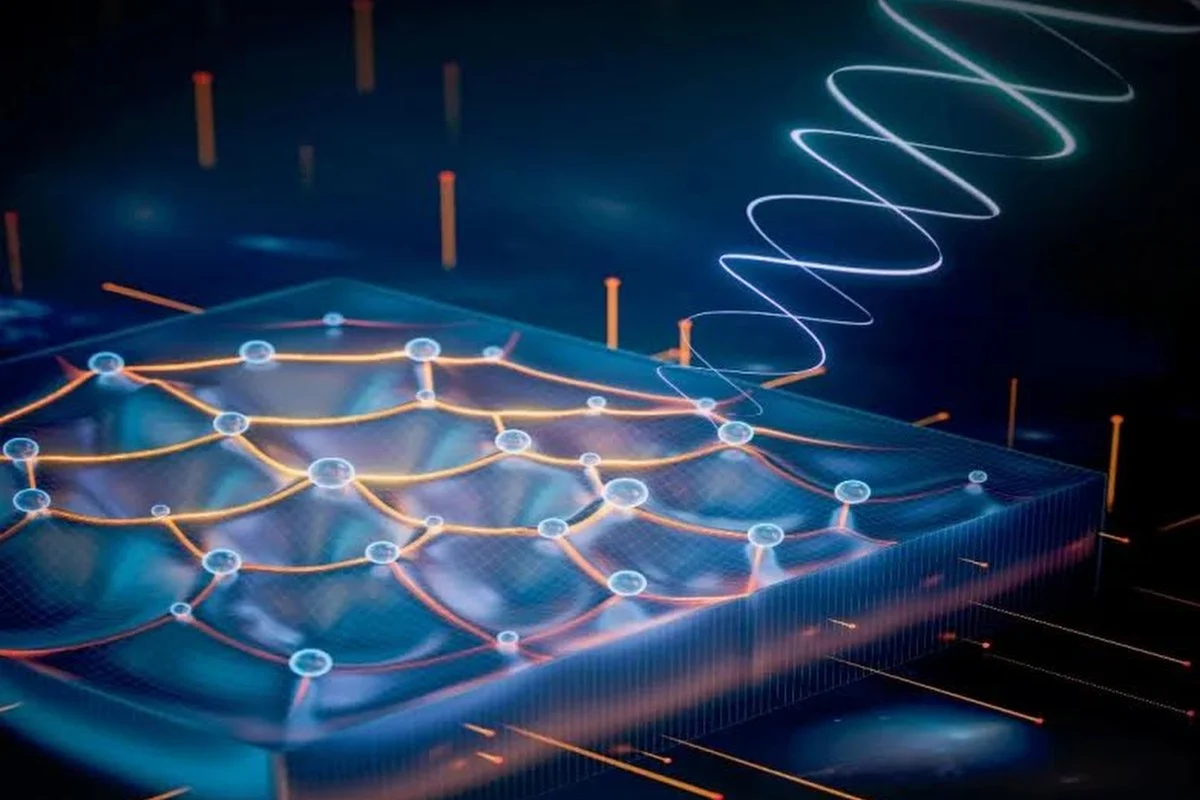

An international team of scientists, led by researchers from Nanjing University, has provided the first experimental evidence hinting at the existence of gravitons, theoretical particles that mediate the force of gravity. By exciting electrons in a semiconductor under extreme conditions, the team observed behavior consistent with predictions about gravitons, marking a significant step towards bridging the gap between quantum mechanics and general relativity. This discovery, published in the journal Nature, opens new avenues for the search for gravitons in laboratory settings and could lead to new insights into the fundamental forces governing the universe.