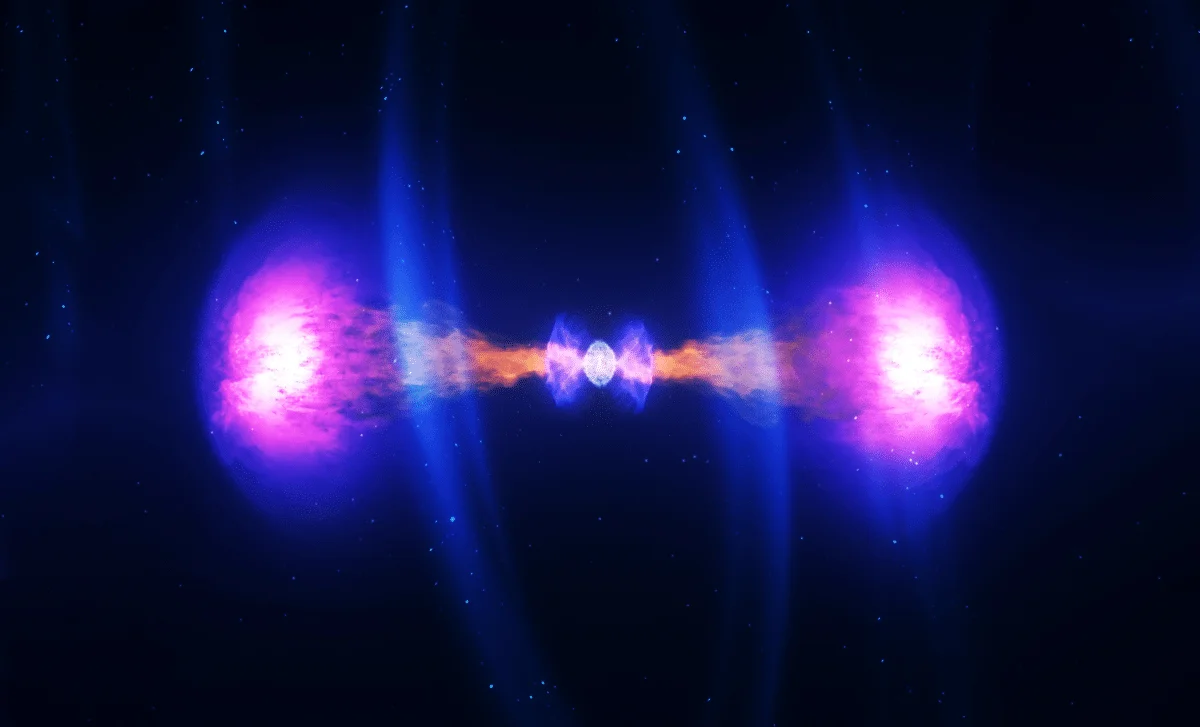

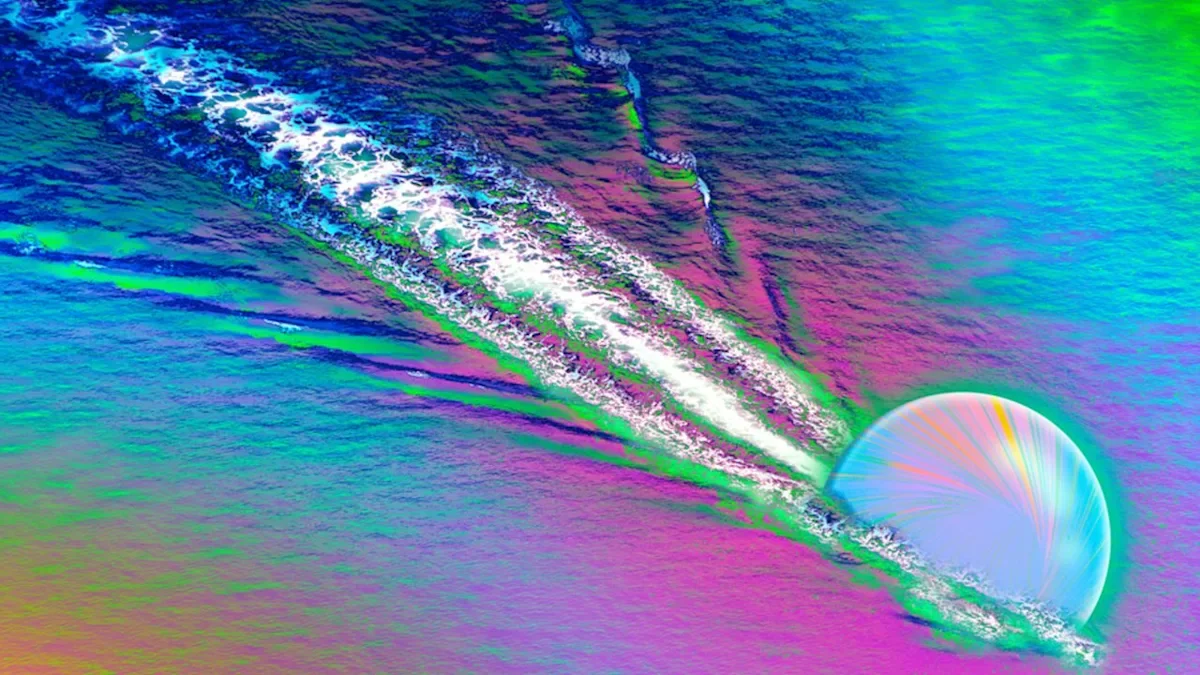

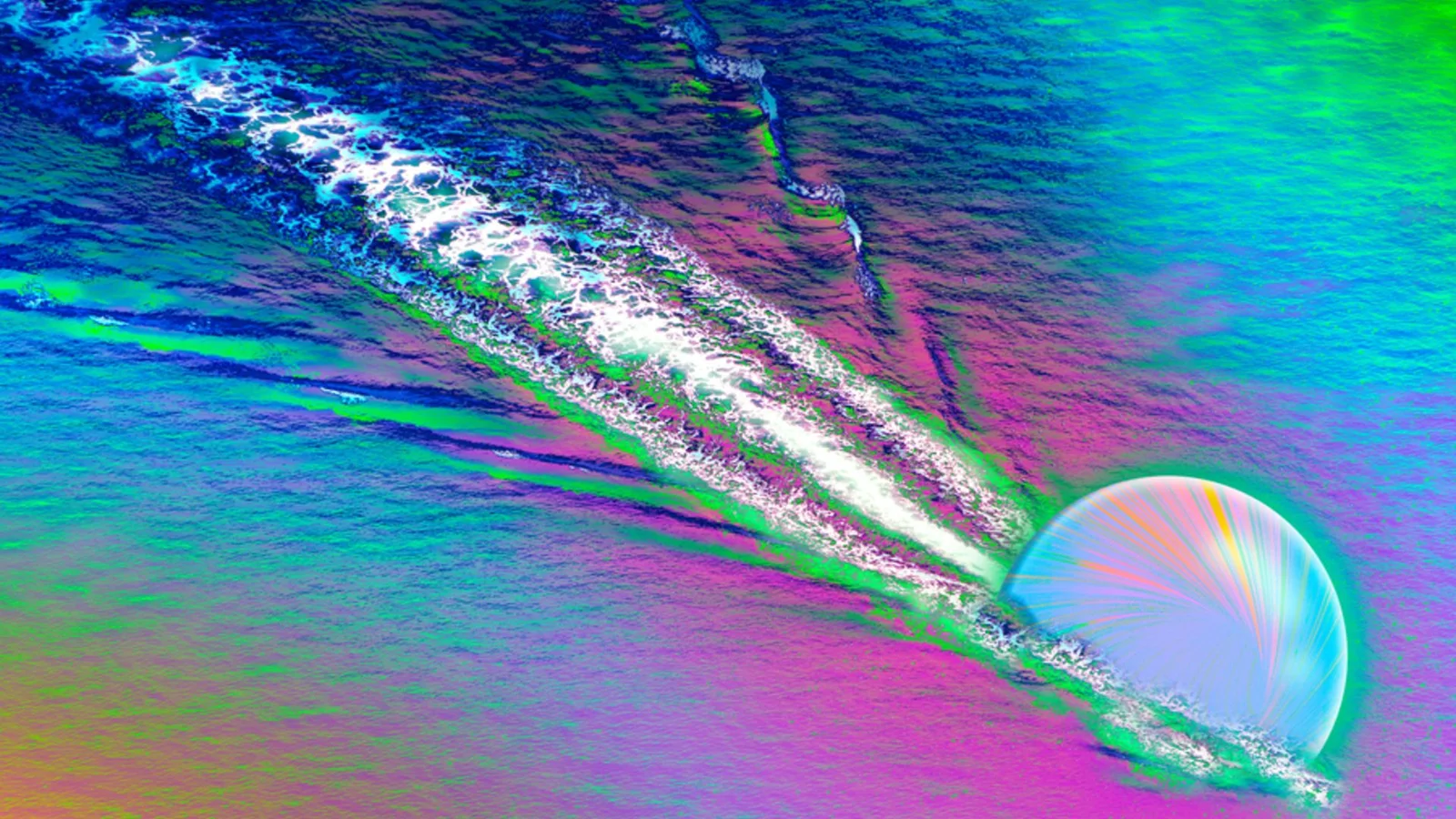

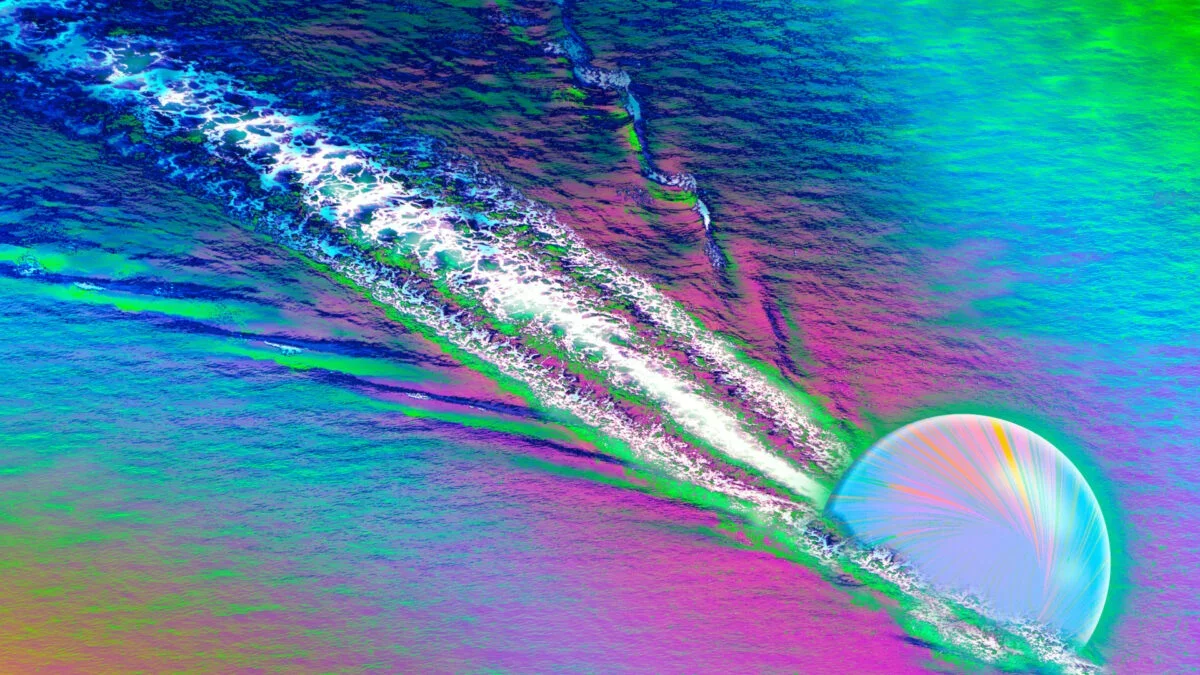

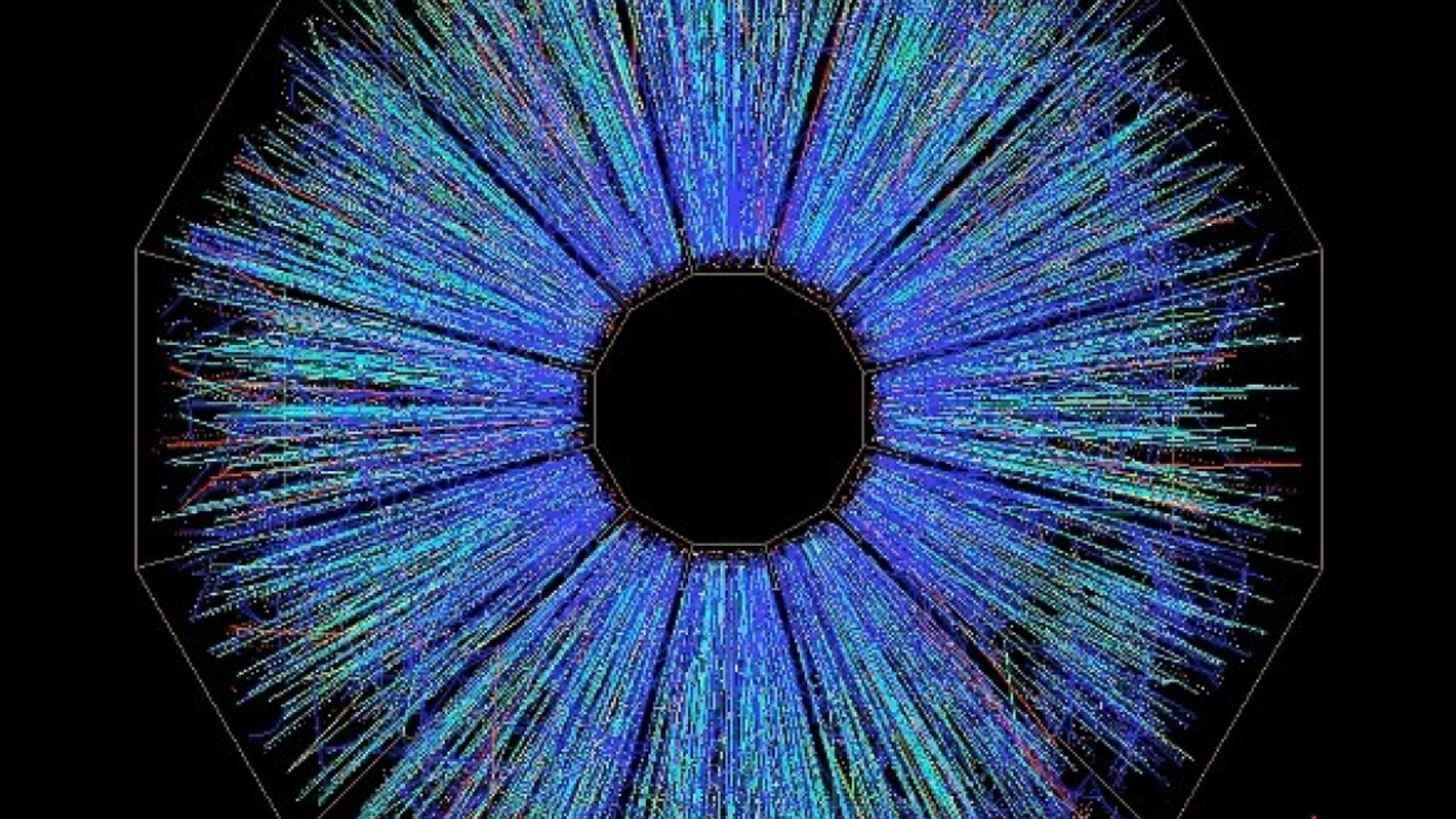

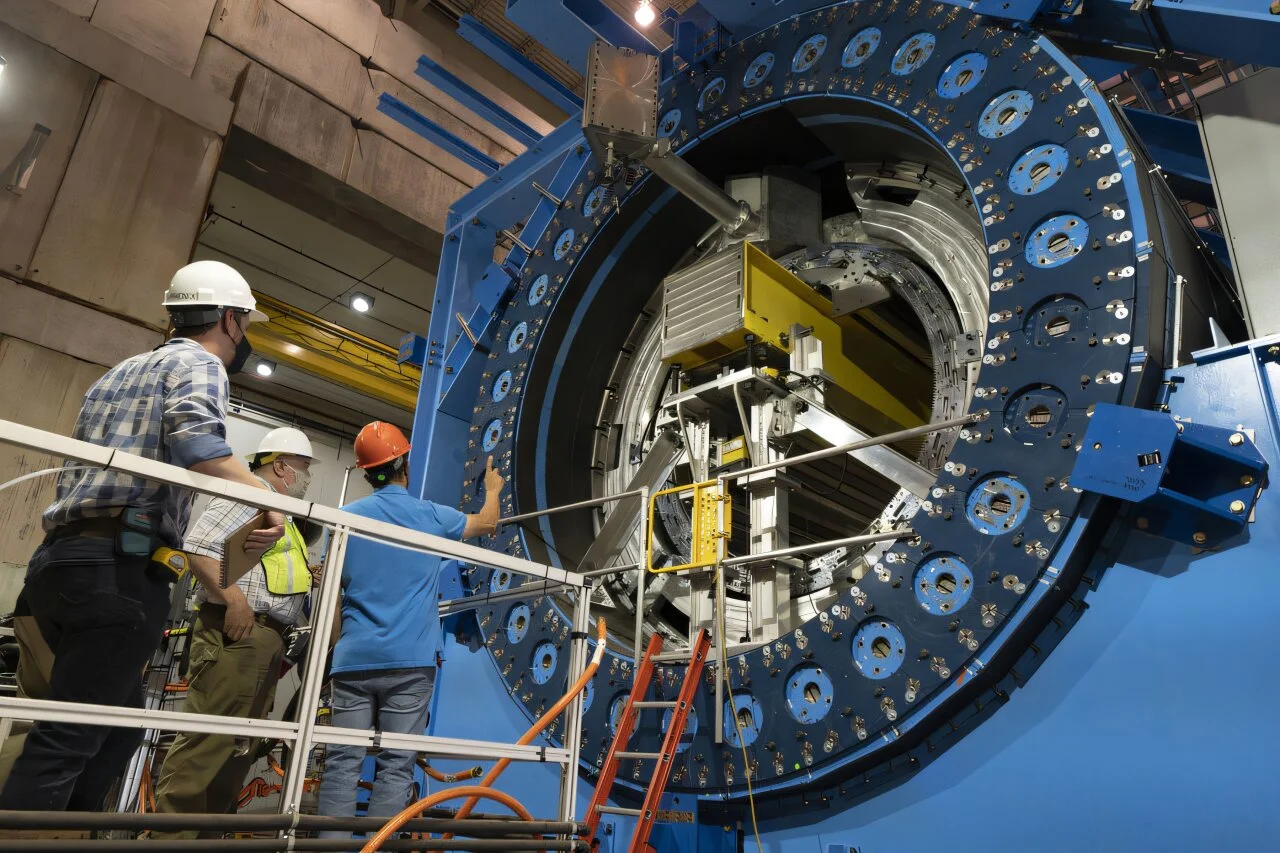

Primordial Soup Demonstrated: Quark-Gluon Plasma Flows as a Liquid in LHC Collisions

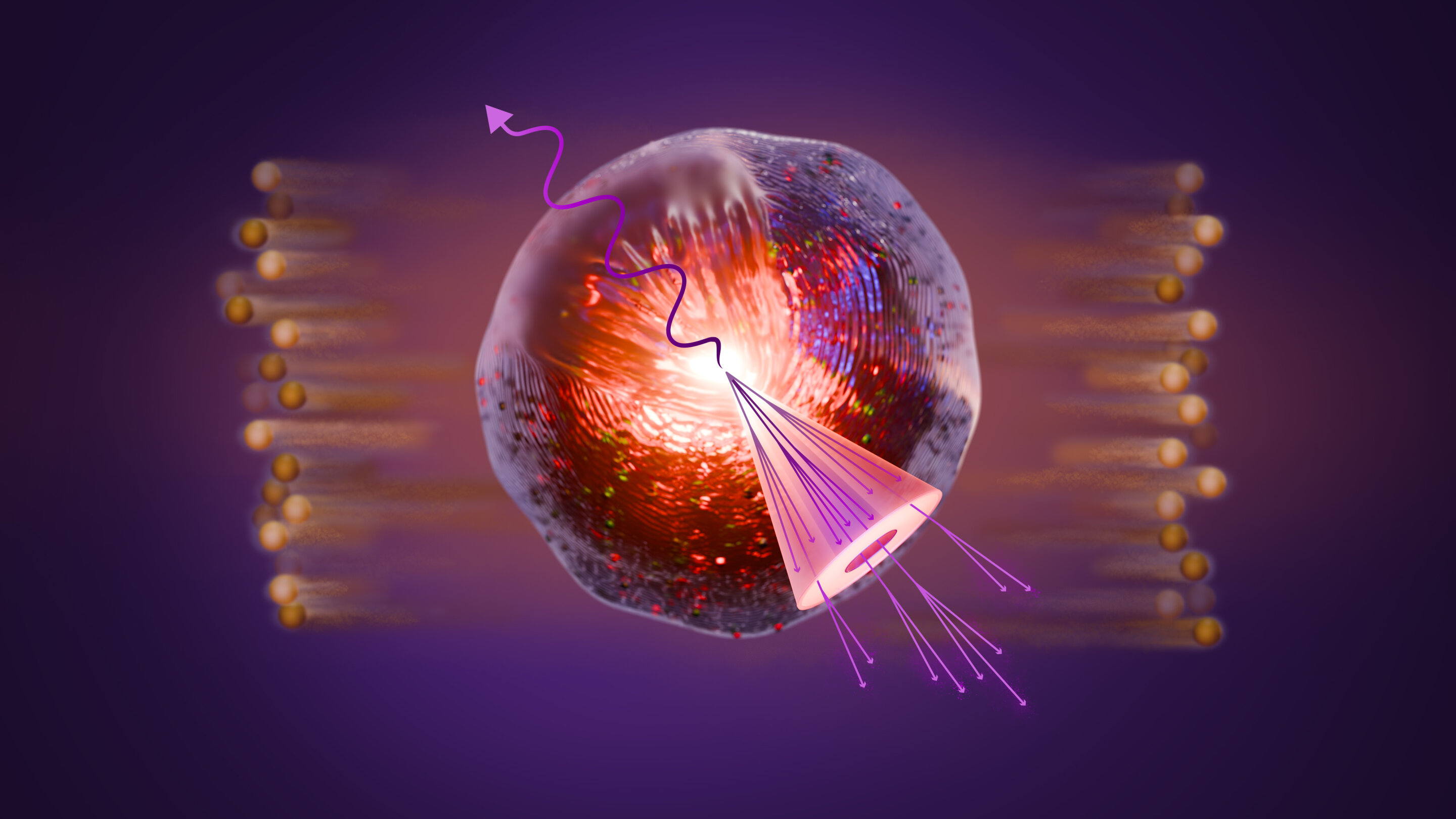

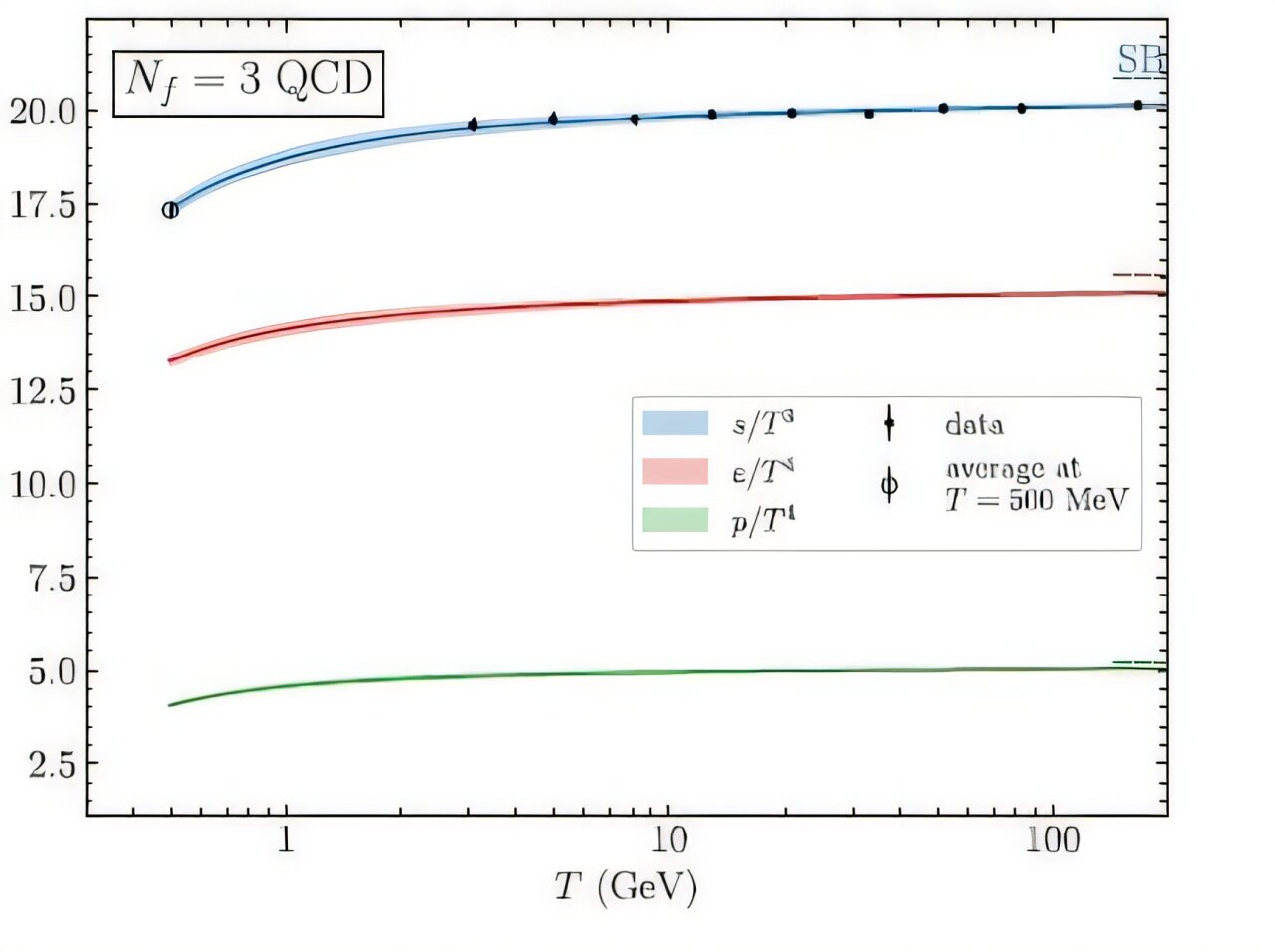

MIT and CERN recreated early-universe conditions by colliding lead ions at near-light speed in the LHC, tracing how quarks slow and generate a wake in quark-gluon plasma, providing definitive evidence that this primordial soup behaves like a liquid rather than a gas, with implications for understanding the birth of matter.