Hidden Atomic Patterns Uncovered in Metals

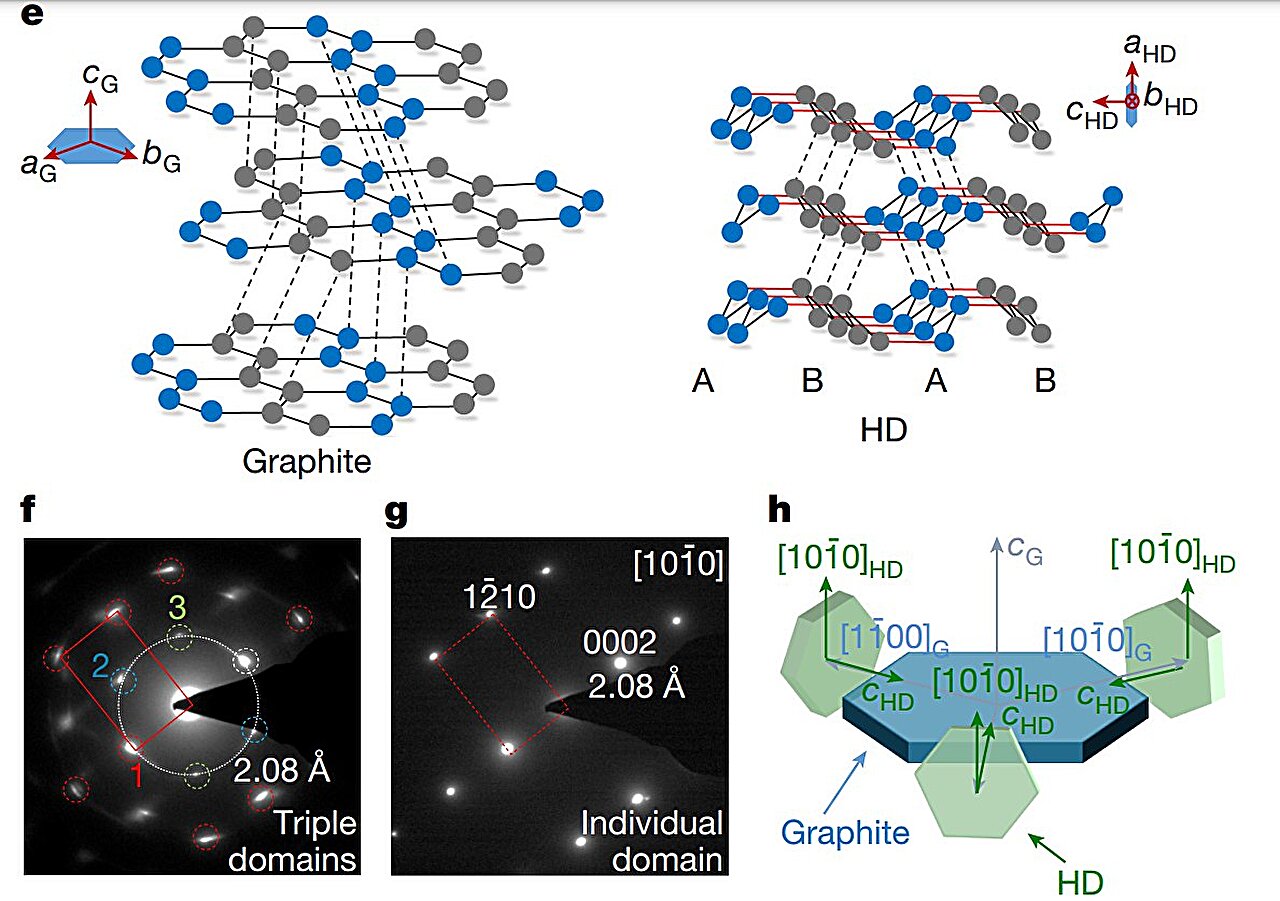

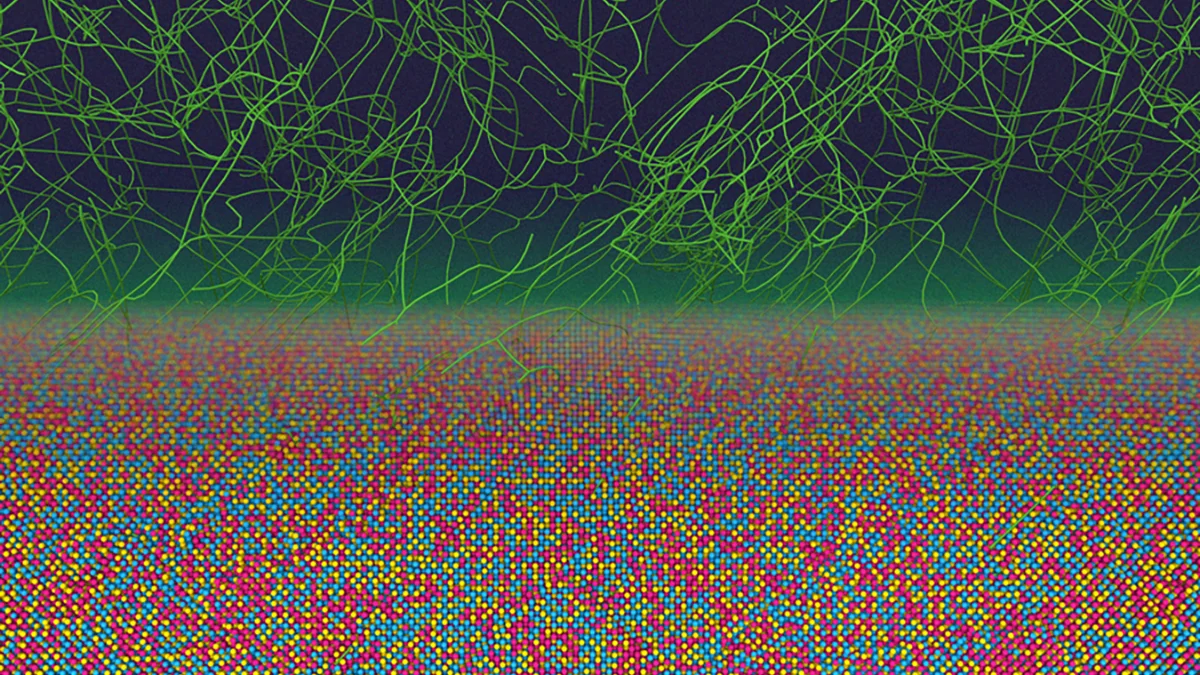

New research from MIT reveals hidden atomic patterns in metal alloys that persist after manufacturing processes, challenging the assumption of complete randomness in atomic arrangements and opening new possibilities for controlling metal properties.