Ancient Teeth Reveal New Insights into Human Evolution

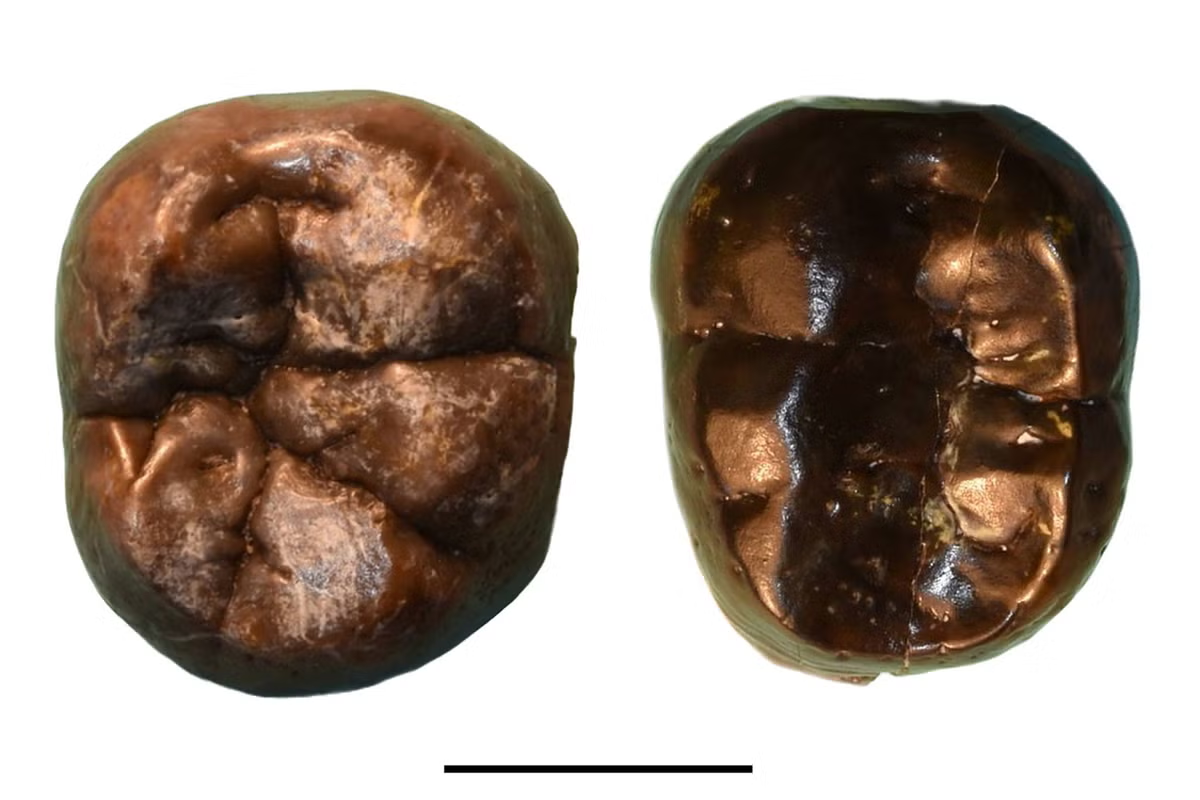

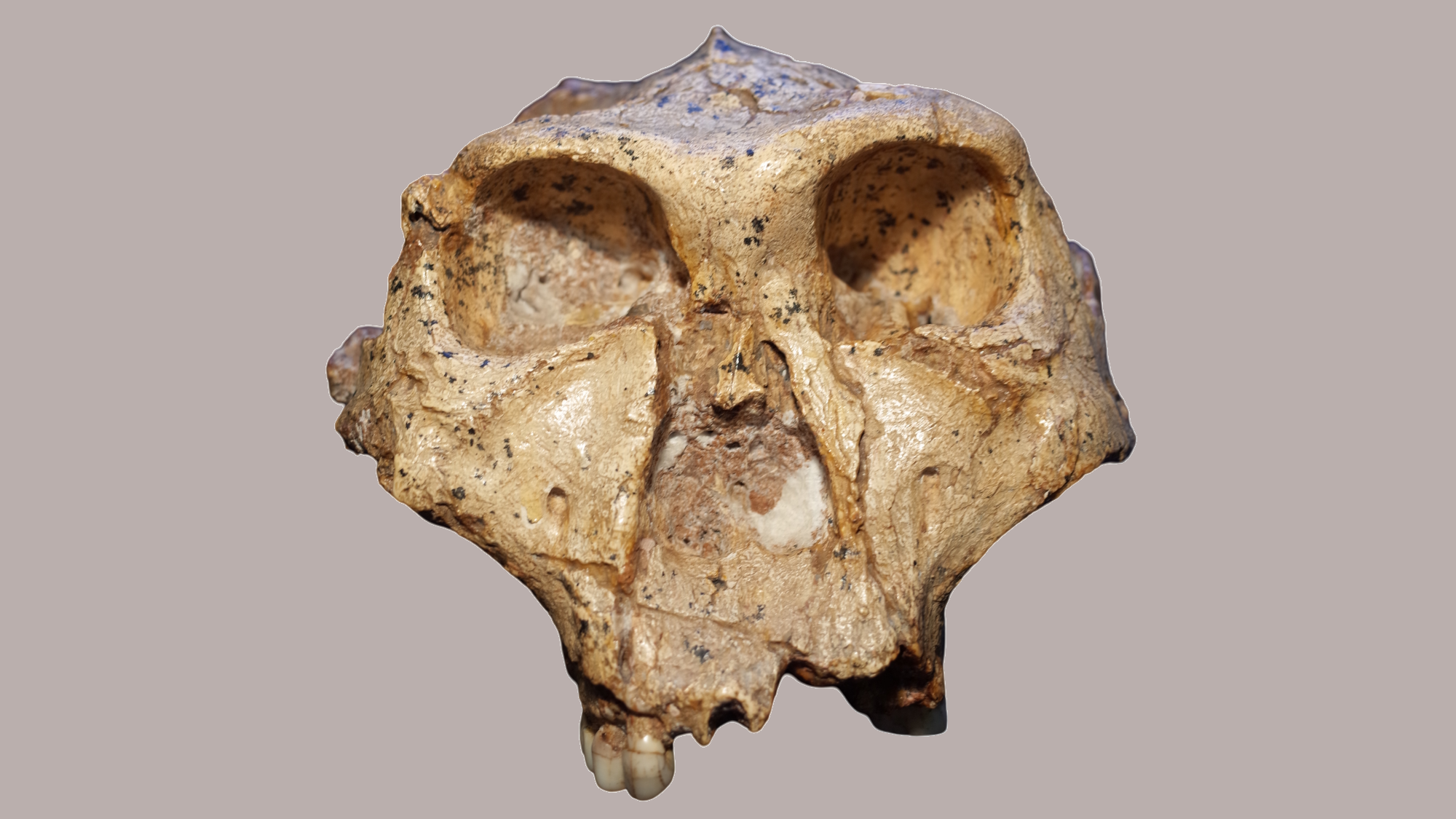

New research suggests that clusters of shallow pits on the enamel of teeth from Paranthropus relatives are likely genetic markers, not disease, providing potential insights into human evolutionary relationships and aiding in fossil identification, though further research is needed.