Tiny Nematodes Defy Desolation Beneath the Atacama Desert

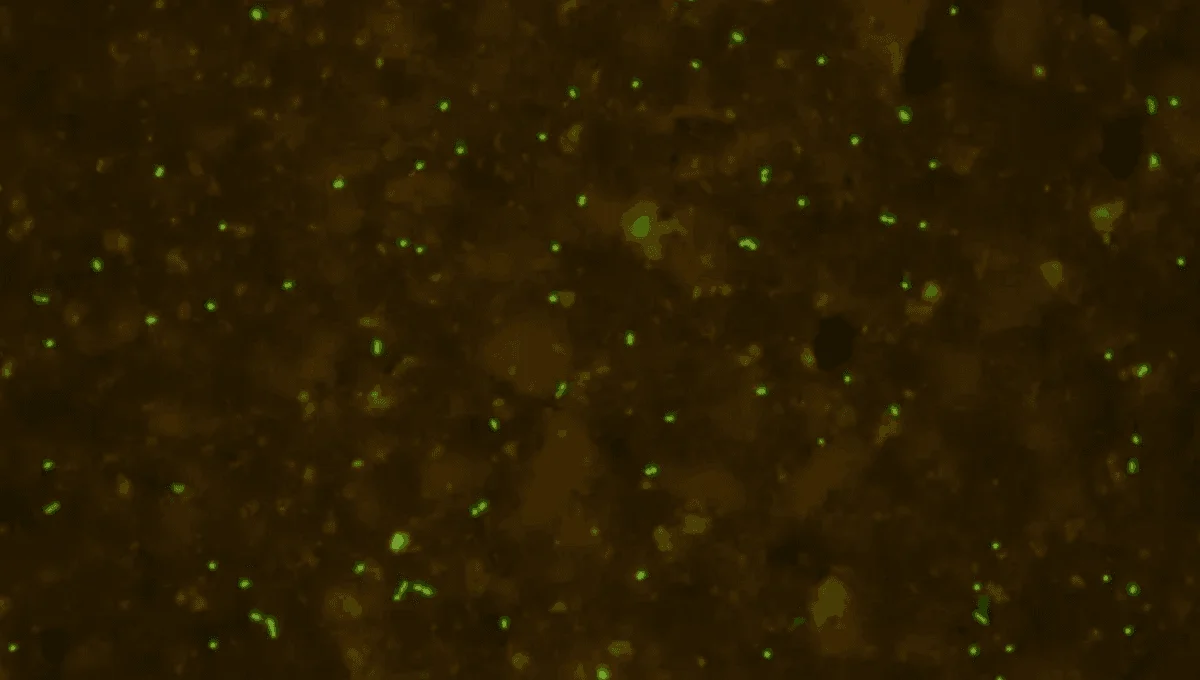

Scientists studying the Atacama Desert discovered thriving nematode communities beneath the surface, showing how multicellular soil life adapts to extreme dryness and salinity, contributing to nutrient cycling and offering insight into biodiversity and climate-change impacts in arid ecosystems.