Hidden Genetic Switches in 'Junk' DNA May Trigger Alzheimer's

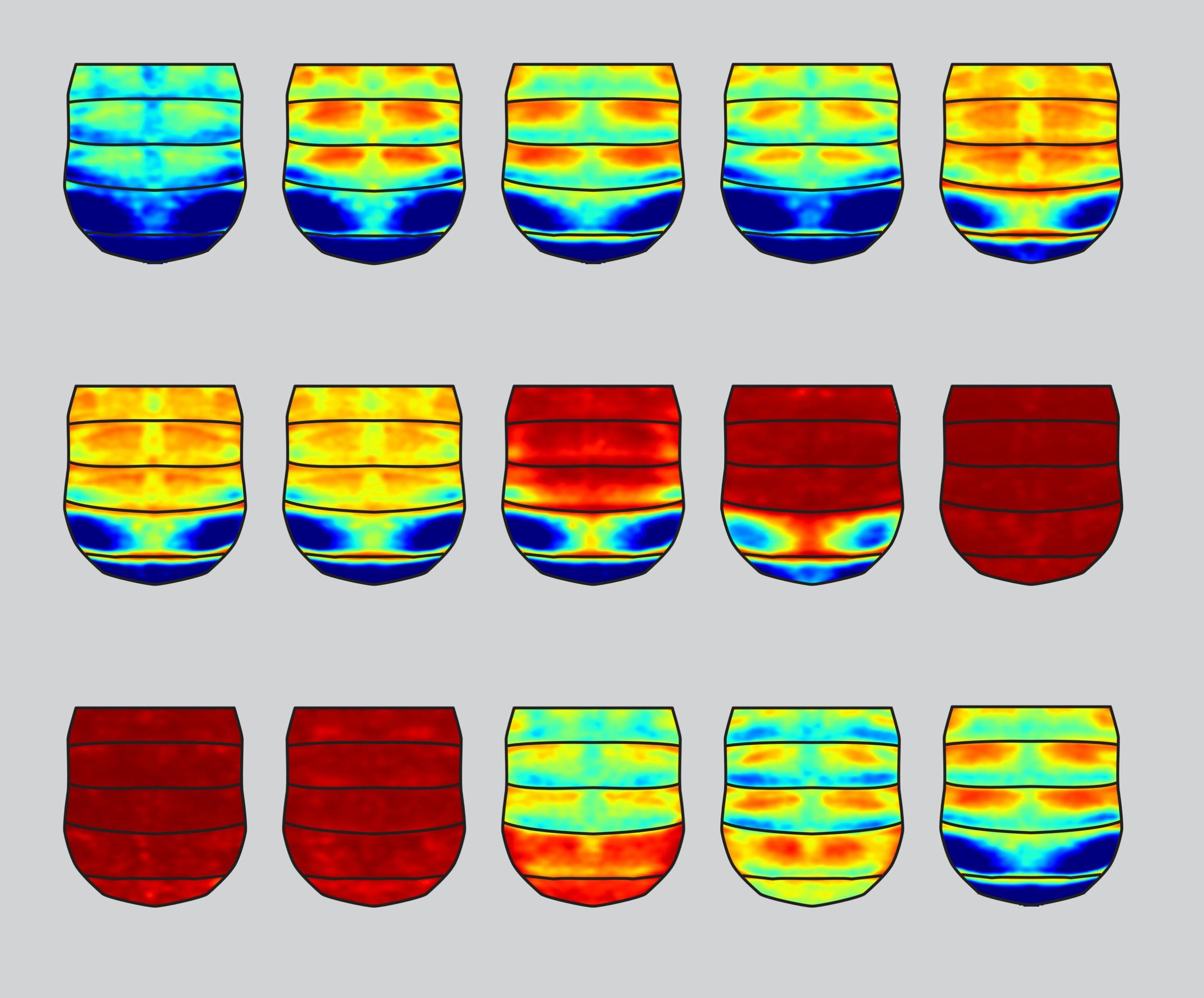

Researchers have identified over 150 DNA control signals in brain cells called astrocytes that may influence Alzheimer's disease, using CRISPRi to study enhancer regions in non-coding DNA, which could lead to new insights and potential treatments for the disease.