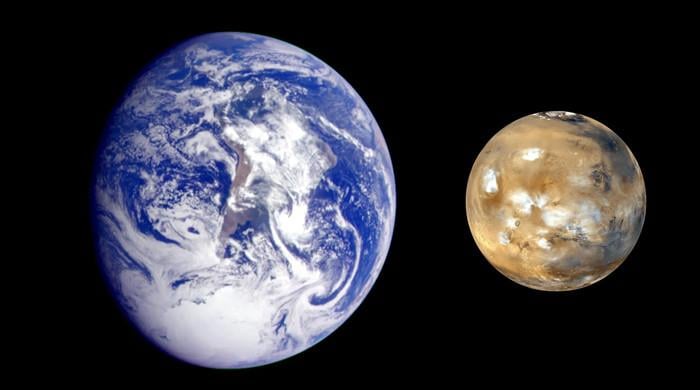

Earth's Ancient Water Surge Reshaped Oceans 15 Million Years Ago

Approximately 15 million years ago, tectonic activity caused Earth's oceanic crust to sink, drastically reducing ocean volume and sea levels by up to 30 meters, while also influencing global climate by decreasing volcanic CO2 emissions and promoting cooling. This event highlights the significant role of geological processes in shaping Earth's oceans and climate, independent of human influence.