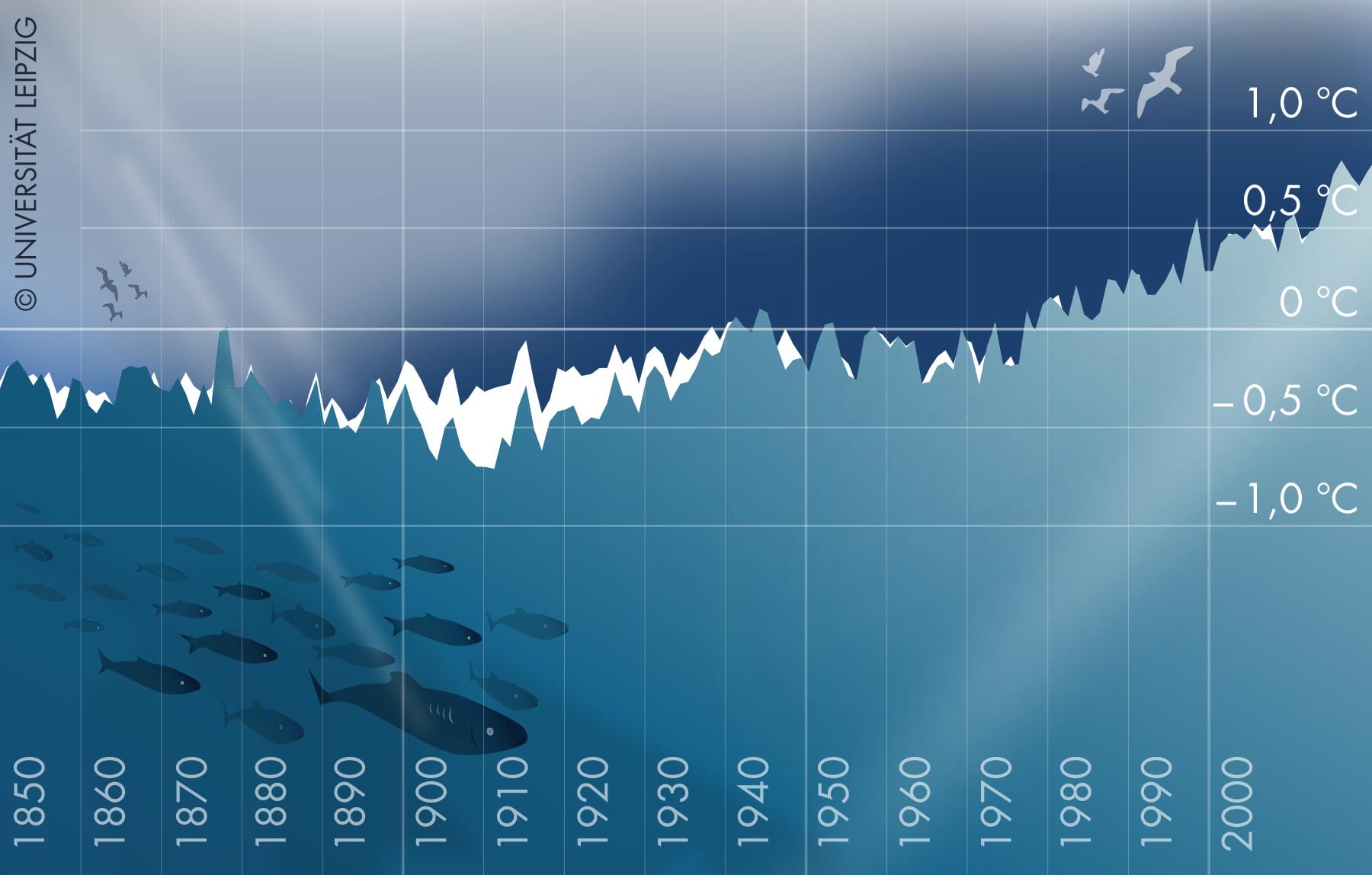

Hidden Ocean Fronts Drive Surprising Carbon Uptake

Two decades of satellite data show that narrow ocean fronts—where water masses meet—are hotspots for carbon capture due to vertical mixing and phytoplankton blooms. These small zones disproportionately absorb CO₂, suggesting climate models may underestimate ocean carbon storage if they ignore front dynamics; incorporating them could improve predictions of the carbon cycle.