Burtele Foot Fossil Rewrites Early Human Family Tree

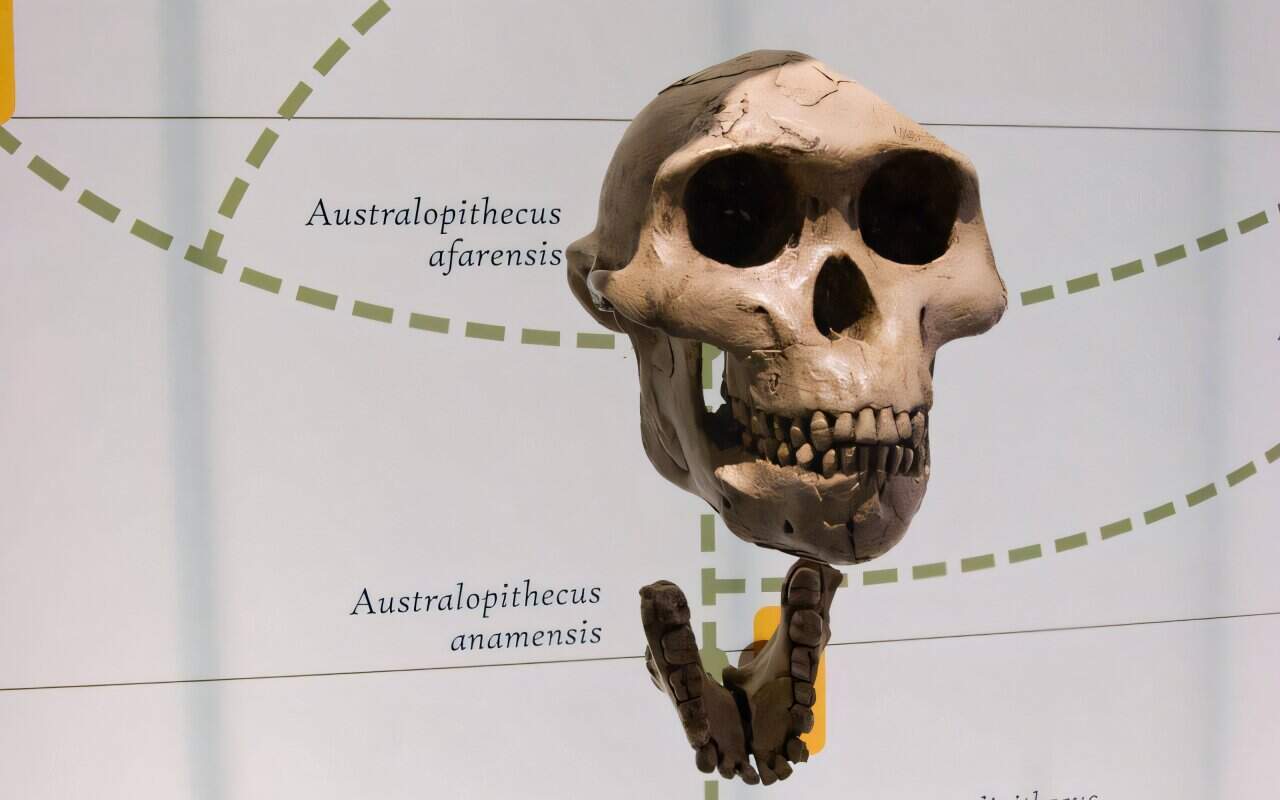

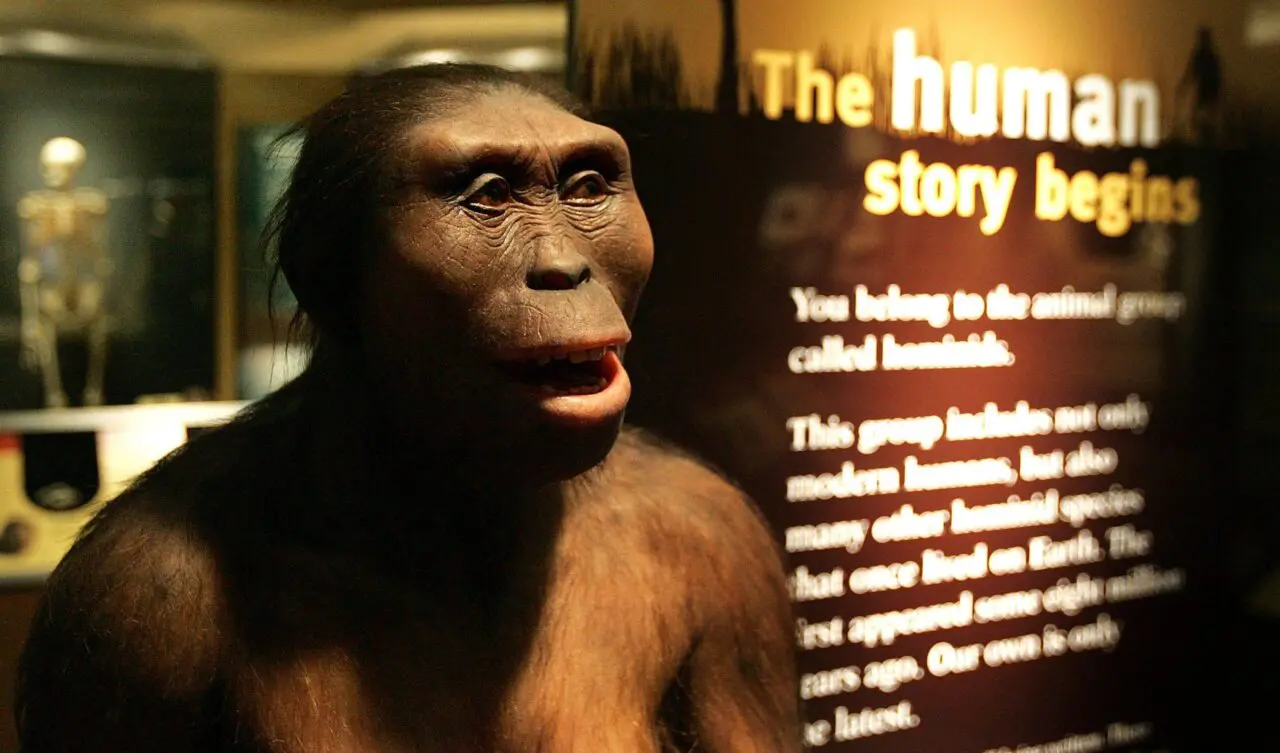

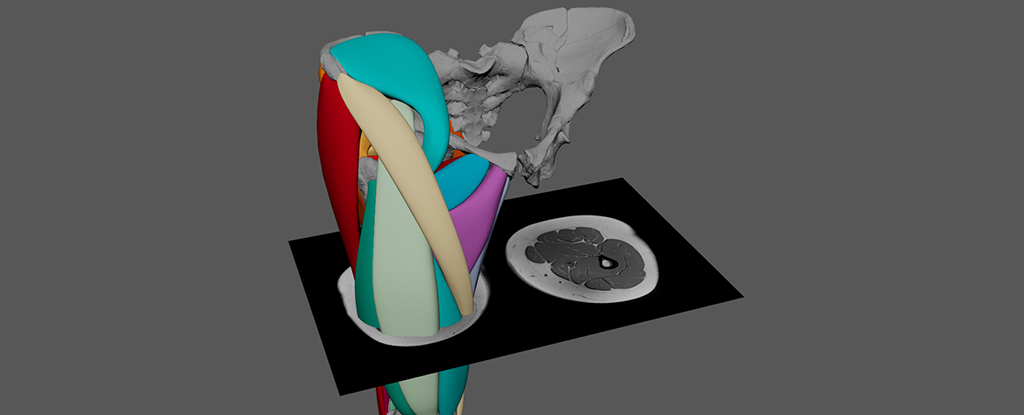

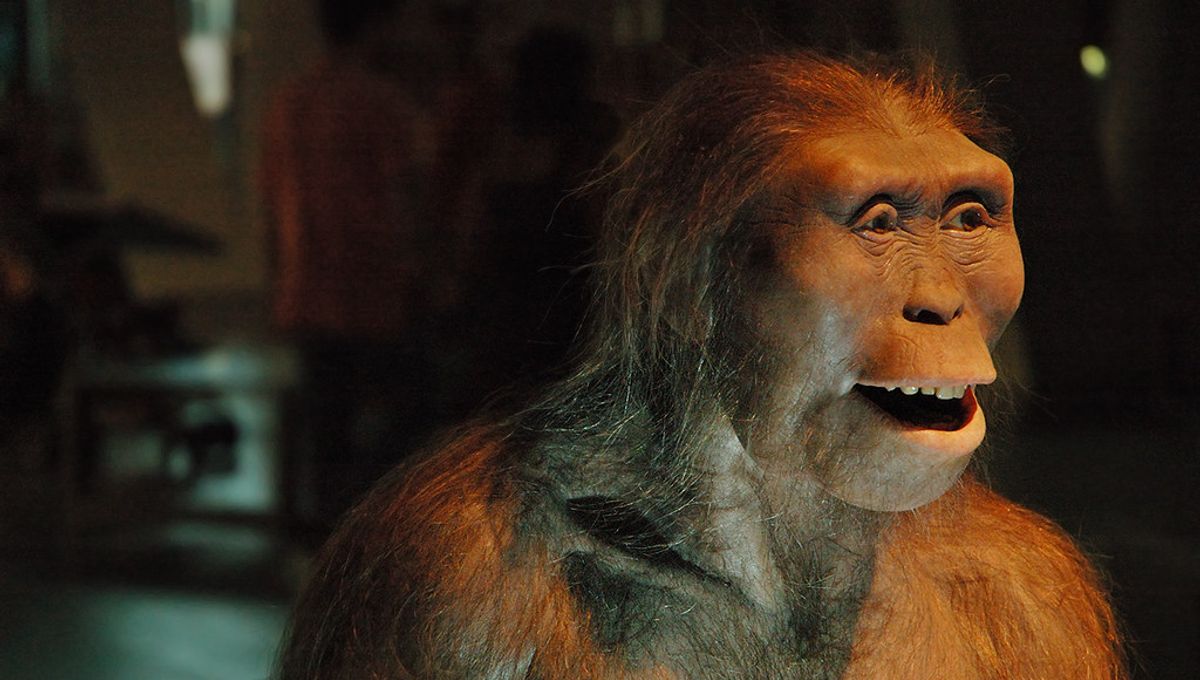

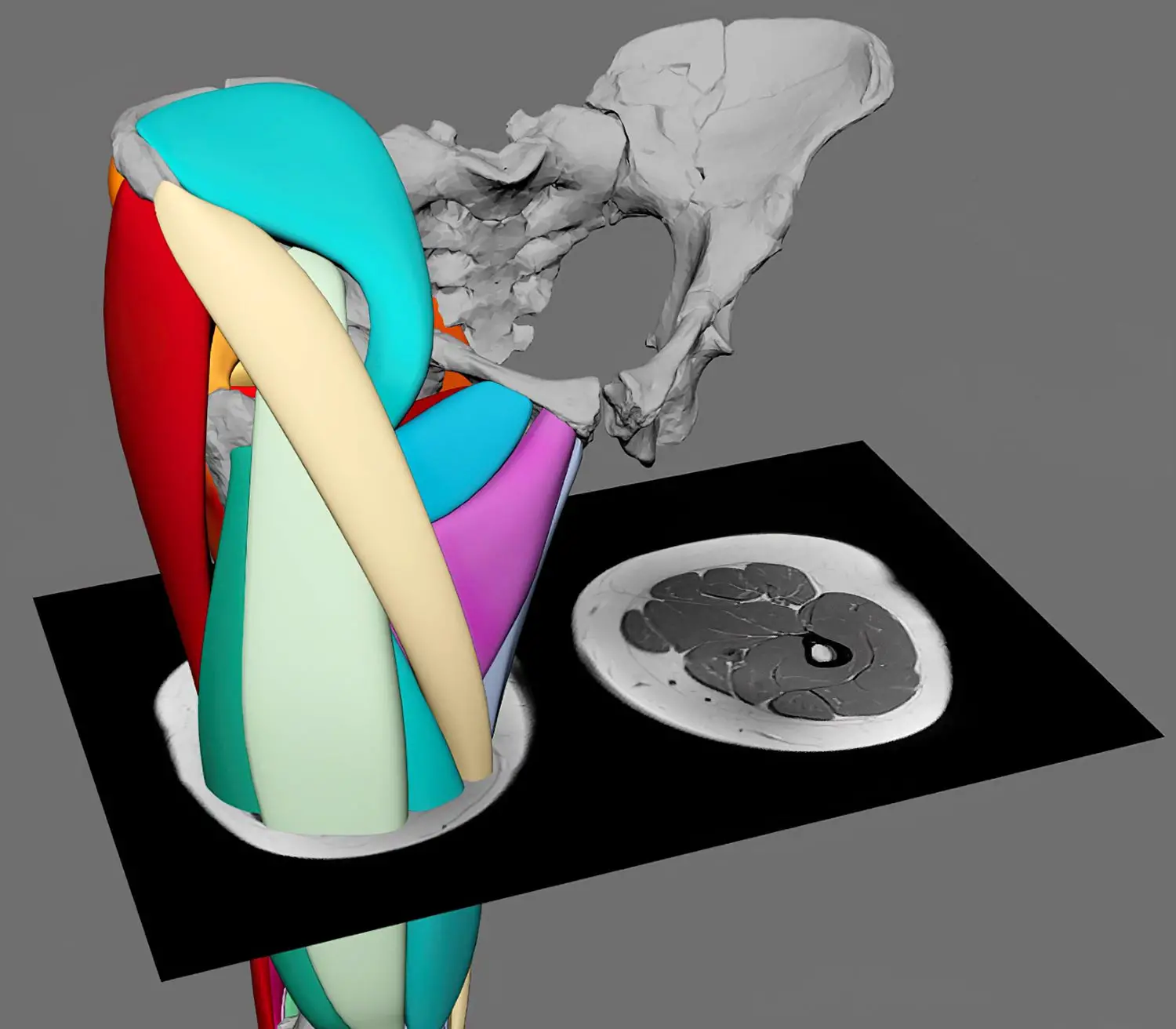

A 3.4-million-year-old fossilized foot from Ethiopia, attributed to Australopithecus deyiremeda, suggests this species coexisted with Australopithecus afarensis (Lucy) and had different locomotion and diet, indicating multiple early hominin lineages and challenging Lucy’s status as the direct human ancestor.